Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Most Exciting Shot at Golf

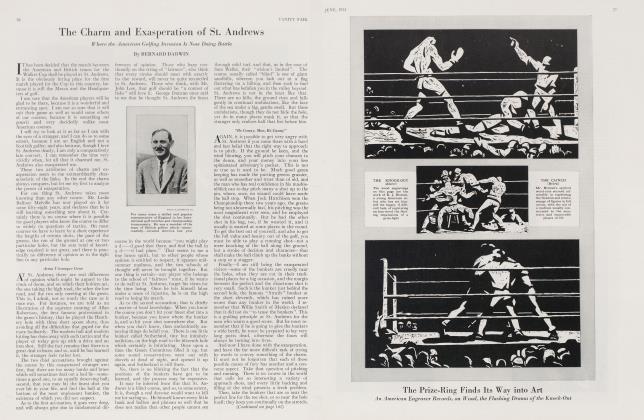

A Bed-Time Conversation in Which Certain Great and Heart-Breaking Tragedies Are Recounted

BERNARD DARWIN

IT was in one of those desultory and interminable golfing conversations, which seem always to begin just when one is wanting to go to bed, that a friend posed me, the other day, with the question "What was the most exciting shot you ever saw?" I know I ought to have risen briskly and firmly and said it was too late at night for so momentous a topic. But I did not; I fell.

What is more I did not answer him at once but fenced a little over his question. Such a shot, I remarked, might belong to one of two distinct categories, apart from the obvious fact that it must come at some great crisis of a great match. It might be a shot more or less ordinary in itself, such as anyone might play, but made dramatic by the circumstances; it might be a short putt such as he or I could generally hole although on this particular occasion it was missed by a great man. On the other hand it might be a shot altogether beyond the compass of the common run of mortals, such as only a great man could play. Which kind of shot, I asked him, did he mean.

HE answered stolidly that he did not know which he meant and repeated his question. Thus he kept me out of bed the longer because I had perforce to choose one of each kind.

As regards the first I had no doubt at all. It was a shot that not only produced the greatest excitement in my own breast and in those of all the onlookers at the time but was richest in exciting, nay in historic consequences. It was a down hill curling putt of a few yards which Mr. Francis Ouimet holed for a three on the seventy-first green in the Open Championship of America at the Brookline Country Club in 1913. It was an ordinary shot in the sense that everybody now and again holes putts of that length and on that slope. It was extraordinary in that no one has probably ever holed a more difficult putt in a more acute crisis. As regards the consequences, think what would have happened if he had not holed it. He would only have had a three at the last hole to tie with Ray and Vardon instead of a four and in all human probability he would not have got it. Ray and Vardon would have tied for the championship which was what everyone was expecting them to do; one of them would have won the play the next day and that championship would by this time be more or less completely forgotten. As it was, that championship may be regarded as marking the beginning of American Golfing Supremacy. No doubt that supremacy would have come anyhow, but it is my firm belief that the fact of the putt being holed accelerated it considerably and the fact of it having been missed, if it had been, would have retarded it. No shot of the same length or, as I think of any length, has ever made so much history.

For my exciting shot, of the second type, I chose another shot played by an American golfer at another seventy-first hole in another Open Championship. It was Mr. Bobby Jones's second shot to the seventeenth at St. Anne's in 1926. He and Watrous, as all the world knows, were playing together; one of them would, humanly speaking, be the winner; they were all square with two holes to play; Watrous was right down the fairway and Bobby was away to the left on a waste of sand. The last hole at St. Anne's is a comparatively easy four for a good player. Add up all those circumstances and weigh them and admit that any reasonable person was right in expecting Watrous to gain a precious stroke at the seventeenth and hold his advantage at the last. And then Bobby took some almost contemptuously small iron and hit a carry of 170 yards or so, off the sand and over hills of sand, right on to the green.

Poor Watrous!

"One moment stood he as the angels stand High in the stainless eminence of air,

The next he was not—."

That shot finished him. It was a shot that was not merely extraordinary because of the circumstances. One would have cried out as at a portent if it had been played in what we consider an ordinary friendly game. Most people could not play it if they tried from now to doomsday, under any circumstances, just because they have not got it in them. It is simply above their stature.

I HAD now done my duty but even so I did not go to bed. In fact the delay now became my fault and not my interlocutor's because memories began to flood in on me thick and fast. I remembered one shot, not' generally remembered which had made my heart stand still, at the time and I had to tell about It was in an Open Championship at Hoylake before the war. J. H. Taylor had been just coming on to his game, the weather was vile and windy and wet—just the weather to suit him—and I had a "hunch", amounting to a prayerful conviction, that he was going to win. And then, in the qualifying round, nothing could or would go right with him. At one moment he seemed irretrievably out of it but he recovered nobly, he pulled round and with one hole to go all was well. He only had to do the hole in five and he had the wind behind him. A drive, an iron over the cross bunker and almost as far over it as he liked, and he could afford to take three more shots to hole out. But I suppose something snapped.

At any rate, after a perfectly good tee shot, he weakly deposited his second right in that horrid cross bunker and—no doubt it served him right—the ball lay ill. He hacked it out but a good long way from the pin; his fourth shot left the ball a good five or six feet away and there was only one shot left. It had to go in or my favorite would not be playing in that championship, and after an agonizing wait it did go in—I did not see it; just as the ball was struck another onlooker moved in front of me—I only heard a sigh of relief and heaved a prodigious one on my own account. My hunch came true, for Taylor won that championship by a whole hatful of strokes. It was the greatest win of his long career and oh! how near he came not to playing at all.

After that I really did get out of my chair and say that it was time to go but I said it a little half heartedly, I looked just a little reluctantly at the still cheerful fire and I suffered myself to be sent back into the depths of that very seductive chair with a very gentb push. "That's all very well," my friend said "and no doubt these things were quite agonizing but they all have a happy ending; the man who played the shot always won the cham pionship. I want to be told of some crisis that ended unhappily, some stroke, with victory depending on it, which ended in terrific disaster. Come now, what was the most excitingly disastrous shot you ever saw."

AT that I scratched by head. The question must be easy enough to answer but it was not. I racked my brains for somebody who, having two putts on the home green to win a championship, first laid himself a stymie and then knocked the other man in; but all in vain. Certainly I had once seen Braid plunge into the great Cardinal bunker at Prestwick, send two balls, one after the other, glancing off the black timbers over the burn and out of bounds and take eight for the hole. But even so he had retained his game and his tranquility so perfectly as to win at last. It had happened once at Prestwick too that Mr. Hilton took an eight at the Himalayas, and eight at a three hole, and lost the championship to Vardon by two strokes; but I had not seen that—I could only think of strokes which, though disastrous, were not dramatically so—of Mr. Roger Wethered for instance needing, as it afterwards turned out, a four at the last hole at St. Andrews to beat Jock Hutchinson and, pitching lamentably short, taking five. After a perfect drive too and with nothing to do! But that was not exciting—it only cast a gentle melancholy upon the soul. I thought of Duncan going out in Ms fourth round at Sandwich in 1922 with a 68 to do to catch Hagen, arriving on the last tee with a four for his 68, putting his second just off the last green and then throwing up his head and sending his chip half way to the hole. That too was a disaster but it lacked the horrible thrill that comes with a fatal plunge into a big bunker or better still, into a lake or a river with the splash of doom. The nearest I could get to that was a memory of Mr. Edward Blackwell playing the nineteenth hole in a championship at St. Andrews, lying just short of the famous burn and then fluffing the ball straight into it, under his very nose and toes; but there had been something too ignominious for great drama about that.

I did remember one disaster from America, when eleven men played off for the last ten places in the championship at Garden City and poor Mr. "Heinie" Schmidt was just too clever; hit the very top of the ballast board in the bunker in front of the green (and had only to get anywhere over it) a five would have been prodigally brilliant, a mere six would have been good enough and he cut it too fine and took seven. Yes that certainly was a dramatic disaster but it was not quite what I wanted because it contained, although not for the unlucky player, a humorous element. I might have quoted myself as having once put three successive shots out of bounds at a nineteenth hole in a championship and having then retired for lack of ammunition but that was too funny also, although I had not appreciated the fun at the time. A short putt missed, on the other hand, is almost too painful and oddly enough the two most painful that I could remember were missed by the same man, Abe Mitchell. One undoubtedly lost him a championship and the other in all probability did so, and not merely one but other potential championships as well. The first was when he still played as an amateur and met Mr. John Ball in the final at Westward Ho! He had a putt of four feet or so on the last green for the hole and match, missed it and was beaten at the 20th.

(Continued on page 106)

(Continued from page 68)

The second was in the Open Championship at Deal in 1920. At the end of the first day Mitchell led the field and especially he lead the most dangerous man in the field, George Duncan, by thirteen shots. Next morning just as he was about to start, rather cold and stiff from unwisely hanging about the tee, in came Duncan with a 71. That did not decrease Mitchell's anxiety but still he played the first hole well enough and laid his third apparently stone dead for a par four. Then he was short, with a tiny putt. Then, instantly, he began to waste more shots and finally killed himself with an eight at the fifth.

Now nobody can possibly say what would have happened but I always firmly believe that, if Mitchell had popped in that little putt, he would have won that championship and if he had won that one, he would assuredly have won some more. As it is he has won many other events and is one of the greatest golfers in the world but he has never won a national championship and it is very possible that he never will. As far as consequences are concerned that wretched little putt has probably as much to answer for as any putt that ever was missed.

As I made that final remark I noticed that my friend was fast sinking into a coma, as perhaps my readers are now; so, at last, we took our candle-sticks and tip-toed upstairs through the sleeping house.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now