Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Charm and Exasperation of St. Andrews

Where the American Golfing Invasion Is Now Doing Battle

BERNARD DARWIN

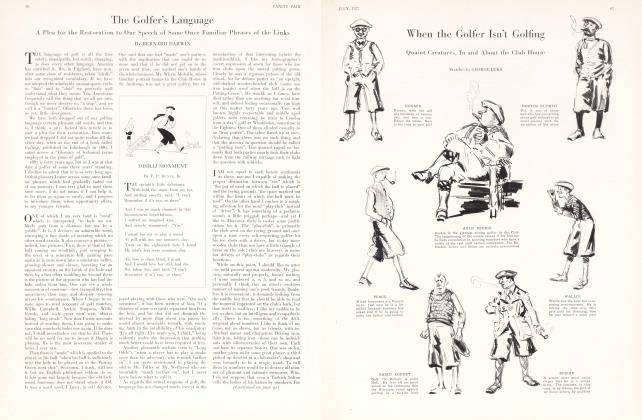

IT has been decided that the match between the American and British teams for the Walker Cup shall be played at St. Andrews. It is the obviously fitting place for the first match played for the Cup in this country, because it is still the Mecca and the Headquarters of golf.

I am sure that the American players will be glad to be there, because it is a wonderful and entrancing spot. I am not so sure that it will suit their game as well as would some others of our courses, because it is something sui generis and very decidedly unlike most American courses.

I will try to look at it as far as I can with the eyes of a stranger, and I can do so to some extent, because I am an English and not a Scottish golfer; and also because, though I love St. Andrews dearly, I am only a comparatively late convert. I can remember the time very vividly when, for all that it charmed me, St. Andrews also exasperated me.

These two attributes of charm and exasperation seem to me extraordinarily characteristic of the links. In the end the charm always conquers, but let me try first to analyze the power of exasperation.

For one thing St. Andrews takes more knowing than any other course. Mr. Leslie Balfour Melville has now played on it for some fifty-eight years, and declares that he is still learning something new about it. Certainly there is no course where it is possible for good players who know the course to differ so widely on questions of tactics. On most courses we have to learn by a short experience the lengths of certain shots, the pace of the greens, the run of the ground at one or two particular holes, but the sum total of knowledge required is not great, and there is practically no difference of opinion as to the right line to any particular hole.

Anna Virumque Cano

AT St. Andrews there are real differences of opinion which might be argued to the crack of doom, and on which their holders act, the one taking the high road, the other the low road, and the two only meeting at the green. This is, I admit, not so much the case as it once was. For instance, we are told as an illustration of the supreme cunning of Allan Robertson, the first famous professional in the game's history, that he played the Heathery hole with three short spoon shots, thus avoiding all the difficulties that gaped for the more foolhardy. The modem ball and modem hitting has done away with such tactics and the player of today gets up with a drive and an iron shot. Still the fact remains that there is a great deal to learn, and so, until he has learned it, the stranger feels rather lost.

The two chief accusations brought against the course by this exasperated stranger are: first, that there are too many banks and braes which will sometimes deal out a bad lie—sometimes a good one, to an equally deserving ball; second, that you may hit the finest shot you ever hit in your life, and find the ball at the bottom of the most unpleasant bunker, the existence of which you did not suspect.

As to the first accusation, it goes very deep, and will always give rise to fundamental differences of opinion. Those who harp continually on the string of "fairness", who think that every stroke should meet with exactly its due reward, will never be quite reconciled to St. Andrews. Those who think, with Mr. John Low, that golf should be "a contest of risks" will love it. George Duncan once said to me that he thought St. Andrews the finest course in the world because "you might play a d-d good shot there, and find the ball in a d-d bad place." That seems to me a fine brave spirit, but to other people whose opinion is entitled to respect, it appears midsummer madness, and the two schools of thought will never be brought together. But one thing is certain—any player who belongs to the school of "fairness" must, if he wants to do well at St. Andrews, forget his views for the time being. Once he lets himself labor under a sense of injustice, he is on the high road to losing his match.

As to the second accusation; that is chiefly a matter of local knowledge. When you know the course you don't hit your finest shot into a bunker, because you know where the bunker is, and so hit your shot somewhere else. But when you don't know, then undoubtedly annoying things do befall you. There is one little bunker called Sutherland, tiny but infinitely malicious, on the high road to the fifteenth hole which certainly is infuriating. Once upon a time the Green Committee filled it up, but some sound conservatives went out with shovels at dead of night, and opened it up again, and Sutherland is still there.

No, there is no blinking the fact that the positions of the bunkers have got to be learned, and the process may be expensive.

It may be inferred from this that St. Andrews is a blind course, and so, to some extent, it is, though a real devotee would want to kill me for saying so. He himself knows every little bank and hollow and plateau so well that he does not realize that other people cannot see through solid turf, and that, as in the case of Sam Weller, their "wision's limited". The course usually called "blind" is one of giant sandhills, whereon you lash out at a flag fluttering on a hilltop, and then rush to find out what has befallen you in the valley beyond. St. Andrews is not in the least like that. There are no hills; the ground rises and falls gently in continual undulations, like the face of the sea under a big, gentle swell. But these undulations, though they do not hide the hole, yet do in many places mask it, so that the stranger only realizes half that lies before him.

"Be Canny, Mon, Be Canny"

A GAIN, it is possible to get very angry with St. Andrews if you come there with a hard and fast belief that the right way to approach is to pitch. If the ground be keen, and the wind blowing, you will pitch your chances to the deuce, and your money into your less opinionated adversary's pocket. This is not as true as it used to be. Much good green keeping has made the putting greens grassier, as well as smoother and truer than of old, and the man who has real confidence in his mashieniblick can to day pitch many a shot up to the pin, where, once, no wizard could have made the ball stop. When Jock Hutchison won the Championship there two years ago, the greens being not abnormally fast, his pitching was the most magnificent ever seen, and he employed the shot continually. But he had the other shot in his bag, too, if he wanted it, and it usually is wanted at some places in the round. To get the best out of yourself, and also to get the full value and beauty out of the golf, you must be able to play a running shot—not a mere knocking of the ball along the ground, but a stroke of decision and character—that shall make the ball climb up the banks without a stop or a stagger.

Finally—I am still being the exasperated visitor—some of the bunkers are cruelly near the holes, when they are cut in their traditional places for a big occasion, and the margin between the perfect and the disastrous shot is very small. Such is the bunker just behind the second hole, the famous "Strath" bunker at the short eleventh, which has ruined more scores than any bunker in the world. I remember that Willie Smith of Mexico declared that it did not do "to tease the bunkers". This is a guiding principle at St. Andrews for the man who wants a good score. But he must remember that if he is going to give the bunkers a wide berth, he must be prepared to lay very long putts dead, otherwise the fours will always be turning into fives.

And now I have done with the exasperation, and have the far more difficult task of trying by words to convey something of the charm. It must not be forgotten that each of these possible causes of fury has another and a converse aspect. Take that question of pitching and running. There is no course in the world that calls for so interesting a variety of approach shots, and every little backing and filling of the wind presents a fresh problem.

Then, take the bunkers that are so near the perfect line for the tee shot, or so near the hole itself: they keep you continually on the stretch; they make you use your head all the time; they give an added thrill to every successful shot.

(Continued on page 102)

(Continued from page 76)

Next door to the old course is the new, a very fine course indeed, laid out on what one might call more orthodox lines. Everybody praises it; everybody says— and truly—that if it were anywhere else save under the shadow of the old course, it would be famous far and wide. But, nobody plays on it if by hook or by crook he can squeeze himself into a match on the course. You may get cross with the old course, but you cannot get tired of it, because it is forever showing itself to you from new angles.

There is, too, something about it so tremendously well worth conquering. To me St. Andrews always seems rather a frightening place. Its inhabitants are such good and such pitilessly candid critics of the game, and this same quality of hardness belongs to the course itself. The ground is actually hard—it would have been hacked to pieces years ago if it had not been—and it is unsympathetic. It kicks your ball away from the hole, rather than towards it. The wind blows hard, too, across that big unsheltered stretch; and then just because there are so many golfers and golf has been played there for so many years, you are apt to feel something of a new boy, and a very small, unconsidered new boy at that. But if you can conquer a course that produces in you these sensations, then, for the moment, there seems to be no more golfing worlds for you to conquer.

Moreover, you do feel at St. Andrews that golf is the important thing, and if you are a golfer that is a pleasant feeling. There is nothing quite like the getting there after a night journey from the south, seeing the names of famous clubmakers over the shops, on the short journey from the station to your hotel, and half the population armed with clubs. And then, choosing your time between the couples, lest you be slain, you walk across the turf below the home green to the club, where half of all the golfing friends you ever knew seem to be congregated in the veranda. That may be at ten o'clock in the morning, when the great golf stream has already been flowing round the links for two hours. Twelve hours later, at ten o'clock at night, you may take the same short walk across the turf now wet with dew, and still have to keep your eyes open for flying balls, still see people finishing their rounds by the fading light; there are still a few onlookers hanging over the railings by Tom Morris's shop, idly watching the last twilight putts being holed.

In high midsummer at St. Andrews, golf is an all-pervading, all-ruling, unsleeping deity.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now