Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

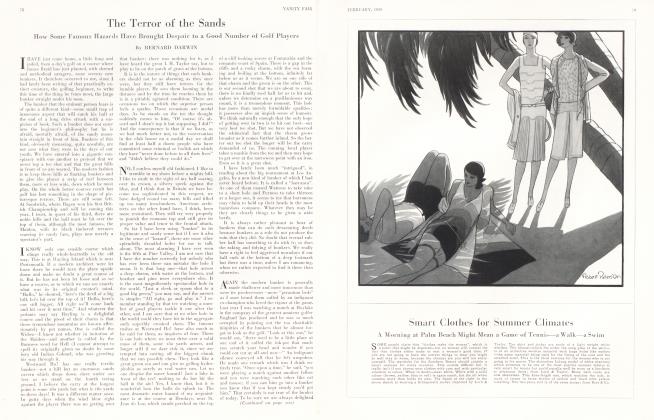

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowGolf a Hundred and Fifty Years Ago

How the Sport of Two Million Americans Began at Leith and Blackheath

BERNARD DARWIN

THE year 1776 is rather a tantalizing one for the man bidden to paint a picture of golf as it was then played by our predecessors. The latter part of the eighteenth century must be set down as belonging to the still gray days of golf. It may be called a transition period: the darkness was ending, the light beginning to shine; but that light in the shape of old records and minute books had not quite yet come. Golf had indeed been played in Scotland for more than three hundred years.

And we have some records. It was in 1457, for instance, that the Scottish parliament had passed that often quoted ordinance that "the futeball and golf be utterly cryit doune" because it interfered with the due practice of archery. It was nearly a hundred and fifty years later that the first golfing martyrs, Robert Robertson and his fellow sufferers for conscience' sake, had been accused of "playing at the gowf on the North Inch, Perth, in time of preaching" and been sentenced to "compear the next Sabbath into the place of public repentance, in presence of the whole congregation". Thus we know that in 1776 golf had long been a popular game but the time of golf clubs and of societies of "noblemen and gentlemen" had only recently arrived. We do know indeed that kings and nobles played the game, and the Royal Blackheath Golf Club, the oldest club in the world, proudly dates its existence from the traditional playing on the heath King James I and his Scottish courtiers,

But that is but a tradition, though like enough a true one.

One of the first hard and fast dates is 1766 (that is a long gap truly from 1603) when one Henry Foot gave a silver club to be played for; and the first Blackheath minute is dated 1787.

The dates of other first minutes arc the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers, 1744, the Royal and Ancient, 1754, the Edinburgh Burgess, 1773.

BEFORE I go on with Scotland and England, let me clear the ground by glancing at two other countries, Holland and France. I will not say much of Holland lest I be involved in a tangle of controversy. Was the game of Het Kolven our golf or was it not? I do not know, but, given a crooked stick and a ball, surely two nations might light independently on the same notion. The charming Dutch pictures which we all know, of a golf-like game on the ice, belong to the seventeenth rather than the eighteenth century. By 1776 it seems that Het Kolven's palmiest days were over, and we may fancy it played, if at all, in narrow alleys or covered courts, wherein men struck a ball at some sort of stake or mark.

In France we have something more to the point in the Jeu de Mail, though here too we find no trace of a hole and the players played along the country roads at a distant mark or goal, striking a wooden ball with a mallet-headed club. The game was in its heyday, we may suppose, in 1776, for as early as 1717 one Lauthier, a professional player, had published a manual on the game. I have read a translation of it and the advice as to the best methods of swinging the club is still good, sound advice for the golfer of today. It was apparently a well bred, a genteel game, for Lauthier told his pupils to play in gloves, and the illustrations show an elegant gentleman in a three-cornered hat, knee breeches and a full-skirted coat—clearly a gentleman who thought something of himself. Montpellier, in the South of France, was the St. Andrews of the Jeu de Mail; and here comes a pleasant little point—we may fairiy imagine that many a Scottish gentleman played it then, for Montpellier was at that time the fashionable wintering place in that part of France. There were many Scotsmen who were driven to France by their adherence to the cause of the Stuarts and they would go where the other smart folk went. So I like to fancy them playing this Frenchified form of golf in default of the real thing and smiling with good-humoured contempt at these silly French mallets. Perhaps the French gentlemen beat them, but what of that? If they could only take these poor ignorant foreigners to the links of Leith, they would show them what proper golf was. "This," they perhaps whispered to one another, "is no gowf at a', jist monkey's tricks."

And now let us flit to the real home of golf, to Scotland, and so to Blackheath. We have one or two definite clues. Many vears before our date, in 1721, a poet had sung:

The vig'rous youth commence their sportive war,

And, armed with lead, their jointed clubs prepare;

The timber curve to leathern orbs apply.

Compact elastic to pervade the sky:

These to the distant hole divert their drive;

They claim the stakes who thither first arrive.

Those lines are from a poem called The Clyde, by one Arbuckle of Glasgow, but it is rather to Edinburgh we must look and the famous links of Leith, the original home of the Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers, whose course is now at Muirfield, the scene of this year's championship. It was on these links that, in 1724, was played what a newspaper of the day called "a solemn match at golf" between two personages with a historic flavour. One was Alexander Elphinstone, brother of that Lord Balmerino who in 1746 was to make a gallant appearance on the scaffold, taking off his wig, and donning a plaid cap, to show that he died a Scotsman. The other was the notorious Captain Porteous of the Edinburgh City Guard, the scene of whose death is familiar to all who know Heart of Midlothian. Elphinstone won the match, which was played for twenty guineas and was "attended by the Duke of Hamilton, the Earl of Morton and a vast mob of the great and little besides."

Continued on page 100

Continued from page 84

There also played there a famous lawyer, Duncan Forbes of Culloden, some time President of the Court of Session. In 1728 he wrote of a game not at Leith, but at M usselburgh: "This day after a very hard pull I got the better of my son at the gowf. If he was as good at any other thing as he is at that, there might be some hopes of him."

And now what sort of a game did these golfers play and on what sort of a course? It was surely a rough and primitive course. I doubt if the greens were in any way prepared, and the players drove their balls from within a club's length or two of the hole, taking sand out of the hole to make the tee. Only in a sense can putting have been an easy art and that because the hole, from much digging for sand, must have grown pleasantly enlarged. There were few holes, but, by way of compensation, these few were of fearsome length. This was not the day of ingeniously guarded "one-shot" holes. About 1826 there were five holes at Leith, the longest some 490 yards, the shortest 415. And 490 yards was what Mr. Bob Acres would have called "a good distance" for men who played with the flimsy-shafted, long-headed club and feathery balls. How long they were we may roughly guess from a bet recorded in the Blackheath minutes about that time. In June, 1813, "Mr. Laing offers to bet a Gallon, that in the course of the season he will drive a ball 500 feet, giving him the chance of 10 strokes to accomplish it, and the choice of ground. Mr. Hamilton lays he will not do the above." Now Mr. Laing was a medal winner, one of the best players of his day, and it is unlikely that clubs and balls were better sixty years before that day. So we see that those long holes were really long and the man who could do one of them in six strokes had something to be proud of. There were no "par fours" in those davs.

We may, I thinkr imagine our Leith golfers playing nearly all their strokes with wooden clubs. This was long before the days of the great clubmaker, Hugh Philp, but the clubs had already become reasonably shapely with tapering shafts, thick, padded grips and long, shallow heads. The iron clubs were still ponderous, clumsy bludgeons and were only used for clumsy work, such as the getting out of bunkers or cart-tracks. It was a rough, Spartan game on the whole, but in one respect not so Spartan perhaps as we are disposed to fancy. That the ball should always be played where it lay or the hole given up was not the old game, though conservatives would have us believe that it was. The early code of rules dispels such a notion, and for my part I believe that when these old Leith golfers lost a ball or found it in a place they did not like, they dropped another and allowed their adversaries a stroke for the privilege. They played, as far as we know, only by match play.

It was in 1744 that the Edinburgh Town Council presented the Silver Club to be competed for by "gentlemen golfers", the date to be announced "by tuck of drum". Moreover this competition was not by medal play as we know it, for the regulations laid down "that the candidates be marked into parties of twos or of threes, if their number be great, by lot; that the player who shall have won the greatest number of holes, be victor". The first winner was John Rattray, a surgeon of Edinburgh.

There is just one other thing of which we may feel tolerably certain, namely that when Mr. Rattray got back to Edinburgh he thought no more of his patients for that night.

. . . If he was called out to see one of them he had first of all to steep his head in a wet towel, for he and his friends celebrated the victory with many bumpers of good claret. Perhaps they did not go back to Edinburgh but repaired straightway to Straiton's Tavern or to Luckie Clephan's at Leith itself. At any rate they made merry somewhere, for we have only to read the minutes of the club gatherings later to see that golf was a truly convivial game.

Much the same things were happening, as far as we can tell, at Blackheath, the one place where golf was played at a very early date in England. Here too it was a Scottish company, a company of exiles who earned their money in London and on Saturday's holiday came down to Blackheath to play the game of their native land. For many years, and certainly around 1776, the names of the members of the society were almost all Scottish. True, at the beginning of the Nineteenth Century there was one, a captain of the club, by the name of Christian Gottlieb Ruperti, who certainly was no Scotsman. I can only imagine that he was allowed into that select company because he presented so many "fine turtles" and other delicacies, as set forth in the minutes. In 1787 the Blackheath golfers met and dined at the "Chocolate House" and later at the "Green Man". We must hope that they were doing so in 1776 also.

Blackheath must have been a somewhat lonely spot in 1 776. Even now, when London has crept out to it and past it, when crowds of footballplaying boys have kicked away the sacred turf—at last driven the golfers away—there is something bleak about it. It is a great wide stretch of turf rising and falling in humps and hollows where once were gravel pits. Hard flinty turf it was—I have played on it often—and the old gravel pits, stonier than all the rest, made the chief hazards. In the eighteenth century those pits were still being worked and the golfers kept away from them, but in compensation they had thick clumps of gorse long since departed, save in one corner where it remains "to witness if I lie". There never were more than seven holes on Blackheath and in earlier days there were but five, modelled perhaps on those of Leith. Golf was probably only a Saturday game.

So the golfers fell to their dinner early, drank their claret and their punch, made their bets and away home. I wonder what they talked and betted about in 1776. Perhaps about some foolish speculator (but he would not have been a Scot) who had lost all his money a few years before in betting at golf. I hope they wore red coats with blue facings. A little later red coats were the order of the day; each club had its uniform and there was the fine of a bottle or more on those that did not wear it. So let us, in our picture, assume the red coats, as they were worn by William Innes and Henry Callender, when Lemuel Abbott painted them. When the coach was nearly due let us fancy them drinking as their last toast:

Continued on page 102

Continued from page 100

Haffy to meet, sorry to fart,

Haffy to meet again.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now