Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Golfer's Language

A Plea for the Restoration to Our Speech of Some Once Familiar Phrases of the Links

BERNARD DARWIN

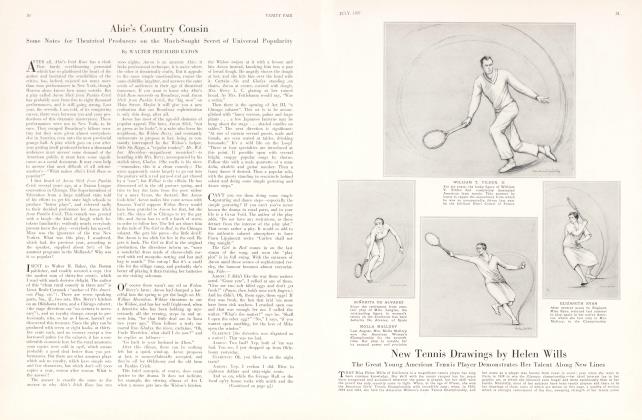

THE language of golf is all the time subtly, impalpably, but surely, changing, us does every other language. America has enriched it. We, in England, have now, after some show of resistance, taken "birdie" into our recognized vocabulary. If we have not adopted the admirably onomatopoeic verbs to "flub" and to "dub" we perfectly well understand what they mean. You Americans frequently call the thing that we all get into, though we never deserve to, "a trap", and we call it. a "bunker". Otherwise there has been, as yet, little divergence.

We have both dropped out of our golfing language certain pleasant old words, and that is, 1 think, a pity. Indeed this article is in part a plea for their restoration. How many we had dropped I did not quite realize till the other day, when at the end of a book called Golfing, published in Edinburgh in 1887, 1 came across a "Glossary of technical terms employed in the game of golf".

1887 is forty years ago, but as I was at that date a golfer of some three years' standing, I decline to admit that it is so very long ago. In that glossary I came across some once familiar phrases which had gradually faded out of my memory. I was very glad to meet them once more; I do not mean, if I can help it, to let them go again so easily, and I propose to introduce them, when opportunity offers, to my younger friends.

ONE of which I am very fond is "steal" which is interpreted "to hole an unlikely putt from a distance but not by a gobble". It is, 1 declare, an admirable word, conveying a fine shade of meaning which no other word can do. It also conveys a picture,— indeed, two pictures. First there is that of the ball coming on stealthily, just creeping to the crest of a miniature hill, gaining pace again as it runs down into a miniature valley, growing slower and slower, hovering for an apparent eternity on the brink of the hole and then, by a last effort tumbling in. Second there is the picture of the opponent who has had the hole stolen from him. One can see a whole succession of emotions—first tranquillity, then uneasiness, then rage and despair—passing across his countenance. When I began in remote ages to read accounts of golf matches, Willie Campbell, Archie Simpson, Willie Fernie, and such great men were always holing "long steals". Now that I write accounts instead of reading them, 1 am going to make sure that somebody holes one again. If he does not, I shall nevertheless say that he did. There will be no need for me to invent if Hagen is playing. He is the most inveterate stealer of holes I ever saw.

Then there is "made" which is applied to the player or his ball "when his ball is sufficiently near the hole to be played on to the Putting Green next shot". Scotsmen, 1 think, still use it but we English philistines seldom do so. It has gone out largely because the old-fashioned foursome does not stand where it did. It was a word used, 1 fancy, in self defence. One said that one had "made" one's partner, with the implication that one could do no more and that if he did not get on to the green next time, one washed one's hands of the whole business. Mr. Whyte Melville, whose familiar portrait hangs in the Club House at St. Andrews, was not a great golfer, but enjoyed playing with those who were. "On such occasions", it has been written of him, "if a distance of some 200 yards separated him from the hole, and his shot did not diminish the interval by more than about ten paces, he would almost invariably remark, with touching faith in the infallibility of his coadjutor: "It's all right; I've made you, I think," being evidently under the impression that nothing much better could have been required of him.

Another pleasantly archaic term is "Long Odds": "when a player has to play a stroke more than his adversary, who is much further on". 1 am quite accustomed to playing the odd to Mr. Tolley or Mr. Wethered who are invariably "much further on", but I never knew before what to call it.

As regards the actual weapons of golf, the language has not changed much, except in the introduction of that interesting hybrid the mashie-niblick. I like my lexicographer's covert expression of scorn for those who use iron clubs upon the sacred putting green. Clearly he was a rigorous person of the old school, for he defines putter as "an upright, stiff-shafted wooden-headed club (some use iron heads) used when the ball is on the Putting-Green". He would, as I fancy, have died rather than use anything but wood himself, and indeed feeling occasionally ran high on this matter forty years ago. Two well known, highly respectable and middle aged golfers were returning by train to London from a day's golf at Wimbledon, sometime in the Eighties. One of them alluded casually to an "iron putter". The other flared up at once, declaring that there was no such thing and that the atrocity in question should be called a "putting iron". The quarrel raged so furiously that both parties nearly took their clubs down from the railway carriage rack to fight the question with niblicks.

I AM not equal to such heroic sentiments as these, nor am I capable of making the proper distinction between "tee" which is "the pat of sand on which the ball is placed" and the teeing ground: "the space marked out within the limits of which the ball must be teed". On the other hand I confess to a sneaking affection for the word "play-club" instead of "driver". It has something of a pedantic sound; a little priggish perhaps—and yet I like it. Moreover there is to-day some justification for it. The "play-club" is primarily the club used on the teeing ground and once upon a time every self-respecting golfer hit his tee shots with a driver, but to-day more wooden clubs than not have a little triangle of brass on the sole; they are brasseys in name but drivers or "play-clubs" as regards their functions.

While on this point, I should like to utter one mild protest against modernity. My glossary, naturally and properly, knows nothing of irons numbered 1, 2, 3, and so on, and personally I think this an utterly soul-less manner of naming one's good friends. Doubtless it is convenient; it demands nothing from the caddie but that he should be able to read the numeral imprinted on the club's back, but that itself is soul-less: I like my caddie to be not a robot, but an intelligent and sympathetic ally. There is too, something of the drill-sergeant about numbers. I like to think of my irons, not as slaves, but as friends, with individual names and characters. Driving iron, light iron, lofting iron—these can be individuals with idiosyncracies of their own. Each can have its separate history. One was stolen, another given us by some great player, a third picked up derelict in a club-maker's shop and seen instantly to be a magic wand. To call them by numbers would be to destroy all manner of pleasant and intimate memories. Why, I do not suppose that even a Turkish Sultan calls the ladies of his harem by numbers. For my part I will have nothing to do with it; I believe the system was invented by a conspiracy of club-makers, just as the match-makers invented the superstition that it is unlucky to light three cigarettes from one match.

(Continued on page 92)

(Continued from page 66)

There is a very charming and very rare old book called The Golfer's Manual by a Keen Hand which was published in 1857. There you may read of an old gentleman who in his foursomes wanted a dashing young partner, who should "keep him up in his swiping". The gap between 1857 and 1887 was, as far as golf was concerned, really a much bigger one than that between 1887 and 1927, and this delightful little book seems to take one back to the dim dark ages. The niblick was then not an iron club, but a wooden one, described as "an antiquated connection of the spoon family, now seldom met with, unless as a supernumerary in the pack of an oldster". The author did not think much of irons; he regarded them as new fangled and dangerous inventions, and his advice for a medal day was to "avoid pressing and by all means try and give your iron clubs a holiday". Incidentally he held that these abominable iron clubs (how different from the graceful and trusty balling spoon!) were "obviously of an unchangeable character". How he would open his venerable eyes if he could come back to see some of the mongrels of to-day!

I am afraid he would find many other things to shock him. He spoke with indignation and horror of anyone who should grip his club with the thumb down the shaft instead of round it; and as for all our modern talk about "concentration" he would, I am sure have had none of it, for he liked the "quotidian round enlivened with varied conversation".

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now