Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMighty Practisers

Noting Those Rare But Admirable Golfers Who Prefer Perfection of Form to Victory

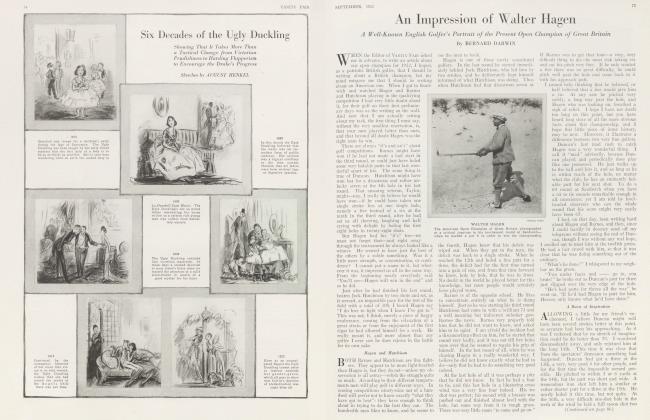

BERNARD DARWIN

IT IS, I am afraid, one of the signs of advancing age not to enjoy or to benefit by practising quite as much as one used to. I have been, in a modest way, a great practiser in my time. I still love it. There is, near my home, a certain solitary valley, curtained by woods, whither I repair now and then with a club and half a dozen halls, and pass a blissful afternoon. Yet I am not sure that I go on so long or am quite so happy as I once was; and as for practise in putting, I arise from my labours with so stiff a hack that I must needs walk a little while as a hump-back before I can straighten myself without agony.

This is a sad state of things, and also a contemptible one, for I know a gentleman of seventy years who, I take it, is in his own way the greatest practiser in the world. I need not leave him in anonymous glory, because in a hook of reminiscences he has confessed as much. So I can say that he is Lord Knutsford, who, though not distinguished as a golfer, is highly distinguished for the great work he has done for the London Hospital, having, since he took its fortunes under his wing, collected for it something over five million pounds.

Sunday afternoon at Lord Knutsford's house is marked by a unique ritual. Some three or four small boys from the adjoining village are mobilized as scouts, under the charge of one rather large hoy who acts as a sort of Sergeant Major or Petty Officer. To him are handed one hundred golf balls of various ages, and one hundred of the now fashionable wooden tees. The army then repairs to an open space in the small park, and the hundred halls are teed in a long row, upon their hundred pegs. All being ready, the master of the house is summoned, together with any rash guests who, little knowing the prodigious exertions they are in for, have been persuaded to join. The boys spread themselves out fan-shaped at an appropriate distance, and the fun begins.

LET no one sneer at the task who has not tried it. The balls are teed within a few inches of one another; no respite is allowed: crack, crack, crack, they have got to go with the rapidity of machine gun fire. An ordinary mortal—I speak from experience—feels after hitting some five and twenty halls that his hands are red hot, that he does not know whether lie is on his head or his heels, that he has only one desire in life, namely, to lean against the railings and pant. He may be allowed to rest, hut he will not escape the scorn of his host, who falls on the remaining balls and dispatches them to all parts of the field with tin* speed of thought. '"That boy out there hasn't had any lately", he will exclaim and instantly the boy in question is made the target for a perfect shower.

When the hundred have all been driven they are collected and brought back. A census of them is held and should there he any missing, that cannot be legitimately accounted for, terrific threats—to be received with the broadest of grins—are launched at the culprits' heads. Then the balls—"all that are left of them,—gallant one hundred"—are teed again and the game only ends with the utter prostration of the guests and the gathering dusk. The last rite follows. In the hall are laid out the right number of plates, each bearing an enormous slice of indigestible-looking plum cake, a shilling and a sixpence. The labourers receive their hire and retire munching, rich and happy. And all this takes place as a rule, let me add, after a real round of golf in the morning on a neighbouring course famed for the steepness of its slopes and the tempestuousness of its winds. It would half kill the youngest of us, but seventy thinks nothing of it.

This singular entertainment hardly comes under the head of practise in the ordinary sense. Practise is generally undertaken with some serious intention of self-improvement. I do not think that Lord Knutsford has any very solemn ambitions in that direction. What he seeks is plenty of exercise and a certain lighthearted joy in the act of hitting. How the hall is hit or whither it goes, save that each scout should have enough to do to earn his cake, appears a secondary consideration.

WHEN I call him the greatest practiser in the world, I am putting him in a class of his own. Among the really serious and theoretical practisers, it is difficult to know to whom the crown should be awarded. He should, I feel almost sure, he an American, since American golfers habitually practise more than ours do—one of the reasons, perhaps, why they play better than ours do. I imagine that Mr. Travis, when he was climbing his way upward to the highest class in golf, must by all accounts have practised as long, as assiduously and as intelligently as any one that ever lived. I have heard stories from his friends of his spending hours and hours perfecting a single stroke; and certainly no golfer ever gave a stronger impression of drilled and mechanical precision of striking.

We had here in England at a rather earlier period of golf, something of a counterpart of Mr. Travis in Mr. Macfie, who won our first Amateur Championship in i885. Like Mr. Travis. Mr. Macfie was not a big or powerful man and owed his success to constant practise in the art of true and easy hitting. He now lives at St. Andrews hut he was a Hoylake golfer in the days of his novitiate. He would go on hitting and hitting till at last the shining of the stars drove him reluctantly homeward and it was always said that the Hoylake Caddies knew their Mr. Macfie had been out practising, by the rich harvest of derelict balls which they reaped early in the morning.

There is an American golfer who must, I think, have come near to Mr. Travis in assiduity. I have never had the pleasure of meeting him, hut I have had that of reading his book, upon which I base my opinion. That golfer is Mr. Marshall Whit latch. There is something truly pathetic in his account of his beginning.

"If I could play golf but once a week. that didn't prevent my practising at home— nearly every evening I went out in the kitchen after the maid had gone upstairs and I was at it. I had the photographs of great players on the kitchen table and I was sure I was doing everything according to the book. Hour after hour I went through this practise, but when I got out on the links my finely-trained strokes wouldn't work. Mornings I would be beaten invariably. Afternoons I would give up form and get there any old way. I always did better afternoons."

This nightmare time passed and he improved rapidly. Except in the matter of consistent putting and it is in respect to putting that his true greatness as a practiser appears for, says he "after an hour or two of practise I could putt with great accuracy." The italics are my own. Fancy a man who talks of an hour or two spent in continuous putting, as if it were five minutes! For years he struggled on, inventing new ways and toiling at them "for an hour or two" at a stretch and then he discovered that they had all been utterly fallacious, that the one thing to do was to relax and not to "set" the muscles, and he lived and putted happily ever afterwards.

It is often urged against our British players that they are decadent, inasmuch as they do not practise as their elders did. That is a controversial topic, hut at any rate some of their elders did practise a great deal. Mr. Hilton was a mighty practiser. The first time I ever saw him he was out playing spoon shots and there seemed to he a fall of snow in miniature on a patch of grass, so closely the one to the other was he dropping the halls. The stroke at which he really worked in his youth was the half iron shot. He could play the high full shot and the wrist shot easily and naturally enough, hut the intermediate distance—ah, there was the rub. However he laboured on and the stone that the builders had rejected became the head of the corner; that half iron shot, once so troublesome, became the one in which he could most confidently put his trust at a crisis.

IF EVER there was to all appearances a golfer who was born and not made, it is Harry Vardon. That perfectly graceful and easy swing looks as if it came untouched from Nature's workshop. Yet Vardon in his young days worked at the game like a Blackamoor. His first job at a little nine hole course, where lie was professional, green-keeper and everything else rolled into one, left him plenty of leisure and he used it to the full. There was one thing in particular at which he toiled, the throwing of the hands well out and hack on the down swing so as not to come down too soon on the hall. This he would practise hour after hour till, he says, he would come in at last feeling so tired and sick that he could not eat his dinner. In his case art has entirely concealed art and so it has in the case of another great player who has practised much, Mr. Bobby Jones. He too looks as if he swung the club by pure natural genius. Yet I doubt if anyone works harder than he does in preparation for some big event. When he was at Muirfield last spring for our Amateur Championship, he retired to a neighboring course whole afternoons together, while George Duncan endeavoured to doctor him for some malady of the iron clubs. Judging by subsequent events the prescription must have been an effective one.

(Continued on page 116)

(Continued from page 72)

These last are examples from high life, but some of the most soul-stirring instances of practise come from humble life. Two of the most inveterate practisers I ever knew were two devoted brothers who lived together and played all their golf together. They played what were, I suppose, nominally matches, hut nobody ever knew who won them and I doubt if the players knew themselves. Each round was only a means to an end. that of trying some new device. Occasionally each was selfish enough to try a device of his very own, hut as a rule they tested them together and undoubtedly came into the clubhouse one day remarking, "We have been trying to use our wrists more". We, who watched them, had a suspicion that one of the two was less fanatical than the other, that he would occasionally have liked a real match and a little less thinking about his arms and legs. But he was much too faithful and devoted ever to drop a hint of such a thing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now