Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSave the Old Masters—from Their Friends

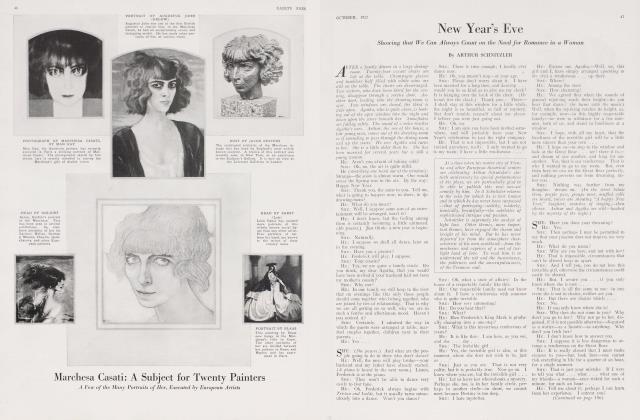

The Battle Between Those Who Love Paintings and Those Who Regard Them Only as Objects of Value

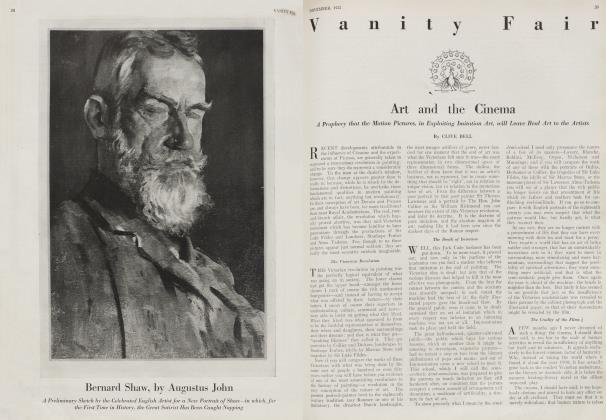

CLIVE BELL

THE men of science, who would please me better were they to show more modesty and take some less sweeping title, are again taking notice of the fine arts. By "taking notice" I mean, of course, laying down the law, that being the only sort of notice that professional gentlemen, be they chemists, biologists, doctors, lawyers or ministers of religion, are in the habit of taking of what they cannot understand. To be exact, then, the gentlemen of science—the chemists chiefly—are again laying down the law about art.

They often do it; last time they laid it down that any painter who has any intention other than that of reproducing exactly what "a man of science" sees, is insane: this is no exaggeration, I heard a whole dinner-table of them agree that they would have certified Conder insane on his pictures alone. But since being thought mad by a mad-doctor has apparently no terrors for a modern painter, our natural philosophers have turned from the moderns to the ancients; and, for the guidance of gallery-directors have promulgated the following:— (a) that it is impossible to remove the dirt, varnish and over-paint from a picture without injuring the original surface, and (b) that old pictures should therefore be left as they are.

Now though on the first of these rulings it would be silly and impertinent for a mere unscientific art-critic, who never dabbled .in anything deeper than H2O, to express an opinion, on the second I do think he is entitled to be heard. What is more, I would suggest that for a mere "man of science" to assert the second is very much what it would be for a mere art-critic to contradict the first.

However, the chemists have found willing listeners amongst the officials; nor is the reason for this agreement between the princes of science and art-direction hard to discover. It lies in the fact that both regard pictures, not as works of art, but as art-treasures. For both a picture is an asset, a national asset or a private, something that redounds to the credit of a nation or raises the social prestige of an individual; for both a picture is something to possess, not something to enjoy. Pictures are treasures, and notoriously the proper place for treasure is the inside of a strong-box; and that, in their hearts, is where most officials would like to keep their pictures.

Art as a National Asset

THE director's safe, they cannot but feel, is the truly appropriate repository for a masterpiece. No kindly man or woman who marked it will have forgotten the melancholy disquietude of the London officials after the signing of the armistice: of course they were glad that the war was over; but must they really believe that there would not be any more air-raids?

Why, then, presumably they must again expose to vulgar eyes those treasures which, during four happy years, they had had, albeit in the dark, to themselves. Again they must hang on the walls of public galleries what had been so much better lodged in the mysterious bowels of the underground railway. What nonsense it seemed. To be sure, in those dark days the public could not see their pictures, but they had them. What more did they want ?

Well, those who regard works of art neither as "national assets", nor as tokens of social distinction, but as means to aesthetic emotion, do want more. They want to see.

They want to see pictures, not to have them; and, unluckily, a good many old pictures are so thickly coated with dirt and varnish that one cannot see them at all. For all aesthetic purposes they might as well be in the Underground still; since to the most curious gaze they present little more than an opaque sheet of brownish glue. They might as well be where officials think they should be—inside a box; and that, indeed, is just where they are, for the sheet of fuliginous and indurated matter on them makes an efficient lid. To this lid it is useless for the satisfied curator to lead us, exclaiming—"Here is the famous portrait by Rembrandt of the Mayor of Dort, which Aelbert Cuyp so much admired; it was painted in 1639 and remained in possession of the family till 1899, when it was purchased by Sir Isaac Hoggensheim (now Lord Stratford-on-Avon) and by him presented, a few months before his elevation, to this gallery"; we are not moved.

We want to see; then we may b.e able to feel. But until we see the picture, we can feel for it next to nothing. This state of mind is, I know, unintelligible to many officials and to almost all chemists; the former are inclined to take it for affectation, the latter know that it is an infallible symptom of degeneracy. All the same, we do want to see.

This is where the chemist comes in; he can put at the service of trustees and reactionary directors impressive arguments against our being allowed to see, and a good deal of moral indignation to boot. Let me tell you, says he, turning sternly on the wretched degenerate, that were I to gratify your preposterous, your indecent, desires, damage would inevitably be done to the surface of the original work: I cannot remove the lid without removing some of the paint with it.

Well, of course, we deplore the fact; nevertheless, we had rather see something than nothing: we had rather have a damaged picture than a dirt-screen. Half a loaf, we perversely maintain, is better than no bread. Being human, we may be tempted to add that there are other chemists who assert that, proper precautions being taken, the cleaner can remove the lid without for a moment jeopardizing what lies beneath it; but if we are wise we shall forbear to trail across the scent a red herring which the adversary is far better equipped than we to follow.

Damaged Pictures vs. Glue

MORE prudently we shall take our stand on the simple contention that half a loaf is better than no bread, and that it is senseless to talk about ruining an old master by cleaning it when there is no old master to ruin,—only a sheet of sombre glue. To this sheet with a great name under it those who care for art will always prefer even an injured picture; while those who are proud of "our art-treasures" will always prefer the glue. There is the matter in a nut-shell—a fair and simple statement of the point at issue.

A fair statement?

Yes; I will prove it by an instance. Not long ago Sir Charles Holmes, who has already done so much to give the old masters in the British National Gallery a chance, and* will do more if the art-treasurers are not allowed to frighten him out of his wits,—Sir Charles Holmes, I say, not very long ago, ordered the cleaning of a picture of the embarkation of St. Ursula, by Claude. For many years this picture had presented to the admiring gaze of connoisseurs little more than a desiccated slop of rich pea-soup through which loomed dimly brown and ochreous forms. The filthy accumulations having been removed, the picture was revealed as a particularly brilliant composition, depending for its design largely on a series of lively notes (flags, fighting-tops and the frocks of the ten thousand virgins) painted in colours as pure and gay almost as those of Fra Angelico or Matisse. No one had ever guessed that anything of that sort lay at the bottom of the tureen, and the treasurehoarders were duly horrified. For them, they declared, the picture was ruined. So it may have been; but that only proves that what they like is the dirt and varnish of two hundred and fifty years, and not what Claude actually painted.

So much for dirt. The other point on which I would insist must appear, I know, to chemists, officials and all those who cherish their national collections but seldom visit them, more preposterous still. For it will happen, sometimes, that you see a picture, not coated with a sheet of cracked tarpaulin, but, on the contrary, highly visible and elaborately painted and bearing the name of an honoured master, who was not, however, the author of what you see. Unquestionably, on the canvas or panel there is a picture by that master; but what you see is the work of someone else who has imposed on the original his view of the matter.

(Continued on page 96)

(Continued from page 67)

Now, what I am going to say must sound, I know, unreasonable; for here you have a fine, bright picture, bearing a greatly honoured name, and this time, what more can a good citizen require? Believe me, I do not like being thought a precious, finnikin crank, a "Francesca da Rimini, nimini-pimini, je-ne-sais-quoi young man" by all people of sound sense and digestion, and yet I do suggest that there is a real and appreciable difference between the work of Signorelli (shall we say) and that of some pupil of Rigaud, who has painted over the Signorelli what he felt sure Signorelli ought to have painted,

For the gentlemen who write letters to the papers about "Our Art-Treasures" such hair-splitting distinctions may not exist; but they should know that there are those, besides the professional artcritics, who notice these things and would gladly see removed from primitive and sixteenth-century pictures, even at the risk of doing some hurt to the underlying originals, all those additions and improvements with which the seventeenth and eighteenth thought fit to embellish them.

The fact is, people who care for pictures are more sensitive in these matters than people who control galleries suppose. See what an atmosphere of interest and excitement pervades the new Venetian Room at the National Gallery, where the pictures have been properly hung against a simple grey background, so that each has a chance of making its own impression. The treasure-lovers are of course furious: "Give us back our red plush," they scream—red plush having become for them the familiar and appropriate tone, not only of a Venetian room, but of a Venetian picture. Now that they see the pictures themselves, in all their subtlety, they can't abide them.

It was a simple picture-lover too, a mere amateur, who once drew the attention of a high official at the Louvre, with whom he happened to be standing in the salon carré to the curious fact that the various masters there represented, though they lived in divers ages and countries, had all given to their pictures the same tone. Now tone, though few chemists are likely to be aware of the fact, is an essential means of artistic expression; but the tone of an old picture in the Louvre, is not, as a rule, the tone chosen by the artist, but the tone imposed by centuries of Paris dirt and varnish. It is not the tone of the master, but the tone of the museum. That is why the Louvre is perhaps the least appetising of all the great European collections.

Had the official deigned to make any reply, doubtless he would have told my amateur that it is unpatriotic to clean pictures.

It is unpatriotic because the pictures in the Kaiser Frederick Museum have been particularly well and thoroughly cleaned; so I quite understand that during the war no English or French man would have cared to clean a picture. But the war is over now, and there is even some talk of making peace. And since our treasures have been brought up from the dark tubes and cellars where they lay hid in the age of airraids, I am suggesting that we in Europe should push the process a step further and make them completely visible.

In America, perhaps, they were visible always. To be sure, you had no airraids; but, unless I mistake, you have plenty of official and other votaries of venerable dust and varnish.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now