Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

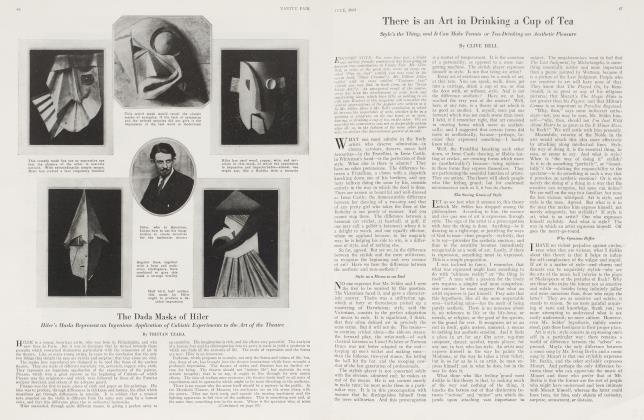

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowArt and the Cinema

A Prophecy that the Motion Pictures, in Exploiting Imitation Art, will Leave Real Art to the Artists

CLIVE BELL

RECENT developments attributable to the influence of Cezanne and the experiments of Picasso, are generally taken to represent a tremendous revolution in painting; and to be sure they do represent a considerable change. To the man at the dealer's window, however, that change appears greater than it really is; because, while he is struck by the deformations and distortions, he overlooks those fundamental qualities in modern painting which are in fact, anything but revolutionary. In their conception of art Derain and Picasso are, and always have been, far more traditional than most Royal Academicians. The real, rootand-branch affair, the revolution which happily proved abortive, was that mid-Victorian movement which has become familiar to later generations through the productions of Sir Luke Fildes and Landseer, Stanhope Forbes and Alma Tadema. For, though to us these pictures appear just normal rubbish: they are really the most eccentric rubbish imaginable.

The Victorian Revolution

THIS Victorian revolution in painting was the perfectly logical equivalent of what was going on in society. The lower classes had got the upper hand—amongst the lower classes I rank of course the rich uneducated bourgeoisie—and instead of having to accept what was offered by their betters by their betters I mean of course their superiors in understanding, culture, sentiment and taste were able to insist on getting what they liked. What they liked was what appeared to them to lie the faithful representation of themselves, their wives and daughters, their surroundings and their dreams: and that is what they got "speaking likeness" they called it. They got portraits by Collier and Dicksee, landscapes b> Stanhope Forbes, idylls by Marcus Stone and tragedies by Sir Luke Fildes.

Now if you will compare the works of these Victorians with what was being done by the same sort of people a hundred or even fifty 1 years earlier you will have before you evidence of one of the most astonishing revolutions in the history of painting—a revolution in the very conception of the nature of art. I he poorest portrait-painter bred to the eighteenth century tradition (say Romney or one of his imitators), the dreariest Dutch landscapist, the most meagre artificer of genre, never fancied for one moment that the end of art was what the Victorians felt sure it was—the exact representation in two dimensional space of three dimensional forms. The dullest, the feeblest of them knew that it was an artist's business, not to represent, but to create something that should be "right", not in relation to vulgar vision, but in relation to the mysterious laws of art. From the difference between a poor portrait by that poor painter Sir Thomas Lawrence and a portrait by The Hon. John Collier or Sir William Richmond you can measure the extent of this Victorian revolution, and infer its doctrine. It is the doctrine of pure imitation, and the absolute negation of art: nothing like it had been seen since the darkest days of the Roman empire.

The Death of Imitation

WELL, this Jack Cade business has been put down. To be more exact, it petered out; and now only in the purlieus of the academies can you find a student who believes that imitation is the end of painting. The Victorian idea is dead; but note that of the various diseases that helped to kill it the most effective was photography. From the first the contest between the camera and the academy was absurdly unequal: in each round the machine had the best of it: the daily illustrated papers gave the knock-out blow. By the general public even it came to be dimly surmised that an art of imitation which in every' respect was inferior to an imitating machine was not art at all. Impressionism took its place and held the field.

The great half-educated, quarter-cultivated public—the public which buys for various reasons, which at another time it might be amusing to investigate, expensive pictures— had to retreat a step or two from the blatant philistinism of papa and mama: and out of Impressionism came a new school to meet it. This school, which I will call the semiaesthetic demi-mondaine, was prepared to give the patrons as 'much imitation as they still hankered after, on condition that the patrons accepted a certain amount of arrangement and decoration, a modicum of artificiality, a tincture in fact of art.

To show precisely what I mean by the semi- demi-school I need only pronounce the names of a few of its masters—Lavery, Blanche, Boldini, McEvoy, Orpen, Nicholson and Munnings; and if you will compare the work of any of these with the portraits of Ouliss, Herkomer or Collier, the tragedies of Sir Luke Fildes, the idylls of Sir Marcus Stone, or the museum-pieces of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema you will see at a glance that the rich public no longer insists on that presentment of life which its fathers and mothers took for unflinching verisimilitude. If you go on to compare it with English portraits of the eighteenth century you may even suspect that what the patrons would like, but hardly get, is what they wanted then.

At any rate, they are no longer content with a presentment of life that they can have every morning with their tea and toast for a penny. They require a world that has an air of being subtler and stranger, that has an unmistakably mysterious side to it; they want to move in surroundings more stimulating and more harmonious, surroundings that suggest the possibility of spiritual adventures; they want something more artificial, and that is what the semi-aesthetic people give themOnce again the man is ahead of the machine: the brush is mightier than the lens. But lately it has seemed to me possible that just as the insufficiency of the Victorian academicians was revealed to their patrons by the cabinet photograph and the illustrated paper, so that of their descendants might be revealed by the film.

The Crudity of the Films

A FEW months ago I never dreamed of such a thing: the cinema, I should then have said, is too low in the scale of human activities to reveal the insufficiency of anything but itself and its admirers. It appeals exclusively to the lowest common factor of humanity. Why, instead of taking the world where it found it about the year 1900, it has actually gone back to the crudest Victorian melodrama; on the literary or dramatic side, it is below the meanest lending-library novel or the silliest west-end play.

The cinema, I should have said, is too hopelessly obvious and unreal to have any effect on the at all civilised. They must see that it is merely ridiculous; that human nature is taboo and the happy ending obligatory; that no complications are admitted; and that the misfortunes which befall the sympathetic characters are never the consequences of the complexities of their own natures but always of impossible circumstances and fantastic misunderstandings. The heroine with a past must never really have had a past at all; the hero suspected of having once told a lie or spent a night out (either sufficient grounds for an irreparable breach) has of course been completely misrepresented—though when he explains the truth to the woman who adores him she does not dream of taking his word till the villain has confessed or documentary evidence has come to light. And the villains and villainesses—naturally they are incapable of a decent thought or of so much as common tact and civility; the brand of Cain is burnt all over them to the tips of their moustaches and ominously white kid gloves, though somehow or other they have hitherto succeeded in taking in the whole world. Meredith's much quoted observation,

"I see no sin:

.In tragic life, God wot,

No villain need be! Passions spin the plot."

would pass for rank heresy, and the height of cynical immorality, in cinema-land.

And I should have gone on to demonstrate that the inability, or unwillingness rather, of the cinema to say anything of interest to the eye was more striking even than its contempt of brain; for it was on the visual side that the possibilities of development seemed boundless. Without dwelling on the stupidity of the production in which, though vast crowds were continually dashing across the stage, no attempt was ever made to give a little character to the business by an incident, by making someone lose his hat or his head, by allowing some 'super' to particularize himself as much as half a dozen sheep in any flock may be trusted to do whenever the shepherd is in a hurry, I should have observed that the standard melodramas were invariably acted in the most commonplace settings.

I should have argued that no attempt was ever made to give accent and intensity by a manipulation—so easily effected with an instrument as pliable as cinemaphotography—of space and proportion; that there was simply nothing to look at, except occasionally a pretty woman or a daring acrobat; that it was all insipid, standardised matter for the million (just what they would get in a dairy restaurant when they went out for tea); and that it could have no effect whatever beyond lowering—if that were possible-^the taste and intelligence of the proletariat. That is what I should have said a few months ago, but since then we have seen the Caligari film, not only in England but all over America.

"Caligari" and Its Signifiance

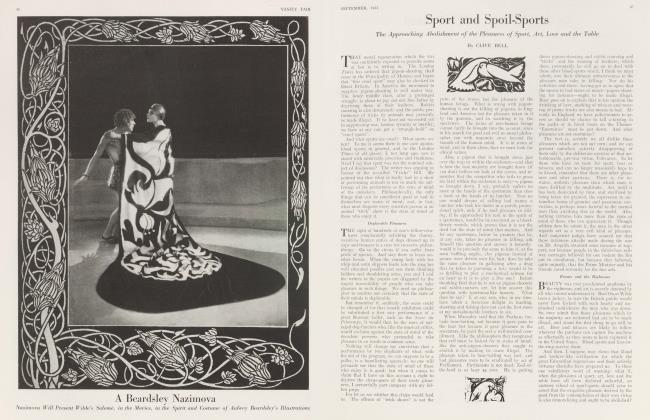

LET no one imagine that I am going to call the Caligari film a great work of art: it is a very poor one. Only, in relation to the ordinary melodramas it is much what the pictures of Orpen and Lavery are to those of Collier and Fildes. There is some appeal to the brain and the eye; there is arrangement and accent; there is a rudimentary, aesthetic intention. Caligari, so far as I know, is the first attempt to create an art of the cinema. To begin with, the story is not wholly contemptible; and it is well chosen because there are things in the nightmare*of a lunatic that can be perhaps better expressed by the cinema than by any other means.

What is more significant, however, are the vfsual novelties; for here, instead of commonplace rooms, streets, parks and prairies, or ape-like reconstructions of the past in the manner of Alma-Tadema, we see an attempt to create a background which shall be at once decorative and appropriate. Dramatic effect is obtained by juggling with proportion and perspectiveAccent and emphasis are imposed on important figures at critical moments by giving them a value which is dramatically correct though quite out of natural proportion. The producers, in a word, have got their effects by employing those means which are the familiar instruments of art.

The Caligari film, then, is not a mere unorganized record of crude events; it aesthetic intention and certain artistic qualities. It may be compared in one respect with the pictures of McEvoy and Lavery, and, in another, with the novels of Compton Mackenzie and Hugh Walpole; at any rate it belongs to a world of thought and feeling complete? different from the world of Frank Dicksee and Marie Corelli. And it does seem to me possible that as the illustrated papers supplanted the Victorian painters, so an art of the cineim developing along the lines adumbrated in Caligari, may come to compete with the Georgians. e

The Breach Between Art and Life

EXPECT no sudden and overwhelming slump to surprise our popular painters; I am not prophesying a catastrophe. But if the cinema, which hitherto has catered almost exclusively for the uneducated, takes to catering for the half, surely those painters and writers who have catered exclusively for the latter must be to some extent affected. And, sup. posing this to happen, what effect might it have upon art? Well, it might hurry on a movement which is going fast enough already. It might widen the breach between art and life, between the artist and the artisan.

So long as there were no cheap daily papers, no photographs, and no steam engines-—till the end of the eighteenth century at any rate— the journalists, illustrators and craftsmen were so mixed up with the artists that there was no sorting them out. The nineteenth centuiy changed all that; and industrial democracy has already its newspapers which have nothing to do with literature, its machine-made wares which have nothing to do with craftsmanship, and its photographic illustrations which have nothing to do with plastic expression. *Up to the present the cinema has competed merely with the reporters, the penny-dreadfulists, the manufacturers of melodrama, and the photographers.

And it is because the Caligari film seems to suggest an invasion of the middle country, of the territory hitherto occupied by those painters and writers who stood between the uncompromising artists and the barbarous horde—painters and writers who while giving the semicivilized public what it wanted inveigled that public into wanting something better than the worst—it is because, in a word, the Caligari film forbodes another victory for the machine on the frontiers of art, for the standardized on the frontiers of the personal, that I am inclined to regard its appearance as an event of some importance.

Should the cinema take to dealing with themes a cut above those of the penny-dread ful and the popular melodrama, should these themes be developed in photographs a cut above the sensational academy-pictures, we may come into possession of a new semimechanical art, but personal art will be driven closer and closer to that stronghold which is inaccessible to the profane. Concerning itself exclusively with purely aesthetic problems, appreciated only by those rare people who are capable of reacting to abstract form, art might become, like the highest mathematics, the preoccupation of a tiny international elite. The great painter of the year 2000 may be to the cultivated public what Einstein is to me. And such a change, though it would make no fundamental difference to art, to life would make a very great difference indeed; it would make it, I think, less vivid and entertaining.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now