Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Dubious Case of Mr. George Moore

A Modern Critic Expostulates This Graceful Laggard of the "Naughty Nineties"

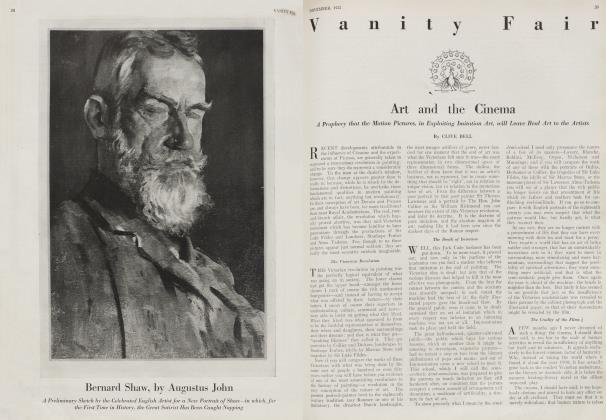

CLIVE BELL

POSTERITY must try not to giggle too much at our passionate admiration for his writings; as every forest has its nightingale, every age of culture has its Stephen Phillips, and Mr. George Moore is the Stephen Phillips of the nineteen tens and twenties. His popularity needs explanation nevertheless: there are hundreds of writers in England and America as bad as George Moore; why to him in particular was the handkerchief thrown?

A possible answer was suggested to me the other day by an entry in the diary (unpublished) of a young officer killed in the last year of the war. This boy, manifestly of superior understanding and sensibility, had, like most of us when young—and even when we are middle-aged—an acute taste for femininity and a prurient mind. This taste he could not gratify: he had gone straight from a public school into the army, and had never known a woman of fashion, though he had gloated over many from a distance. Too fastidious for drabs, or dirty stories, or the crude pornographic literature of the Palais Royal, he suffered the extreme miseries of starvation until he came across La Vie Parisienne. Then he burst into exultation. "I have subscribed for a year to La Vie Parisienne: no one detests more than I smutty pictures and obscene books, but when I get a really artistic thing like this, I can enjoy it with all my being." George Moore may be La Vie Parisienne of the cultured classes.

The Postures of Bourgeois Morality

PERSONALLY, I prefer the Palais Royal— the Place St. Michel is, by the way, a likelier draw nowadays. I prefer the works of MM. Max des Vignons and Aime Van Rod, because I detest the vulgarity of naughtiness. Mr. Moore is as naughty as you would expect a straggler from those naughty nineties to be; he puts out his tongue and t widdles his thumb and says what a bad boy am I. So doing he becomes bourgeois; for only by accepting bourgeois morality can one give oneself the thrill of being immoral. The genuinely free man says what Whitman said—"By God, I see no sin in fornication"—and there's an end of it. He does not create a vaguely purple ecstasy of an indiscretion that is only by the grace of indulgence sinful.

To Mr. Moore it would be too humiliating to realize that he was not a bad man at all, only a braggart. He glories in the name of sinner. And so he cannot leave the subject alone; for ever he must be dragging in metaphors and instances to shock the clergy and show what a devil of a fellow he used to be. He cannot so much as eat a crammed capon without boasting that the bird has been tortured, blinded and forcibly fed for his delectation. He doesn't care a rap; neither do I; so I don't feel called upon to crow when I eat my chicken and asparagus. But all this perversity gives the cultured a delicious thrill, which, however, they don't choose to admit; wherefore, when they praise George Moore, they praise him for—of all things in the world —his style.

A prose style may be both illiterate and stupid and yet possess qualities which justly extort admiration; but, so far as I can see, the only quality that covers the manifest defects of Mr. Moore's is transparent pretentiousness. His is the prose of a dull and none too well-educated fellow, trying to show off. It is an affair of quaint substantives and artistic adjectives used inappropriately because without understanding. He will say "thither" and "whither" when he means "there" and "where", and "unstrange" when he wants to say "familiar"—this last tid-bit, by the way, proves quite too hard for his mental gums, and he writes "your face is not unstrange" when he means "your face is familiar". But, to be as fair as possible, let me take as sample a paragraph from Memoirs of My Dead Life, which has twice been quoted at me as a piece of particularly fine writing.

A Specimen of Moore's Style

"THE spring tide is rising; the almond-trees are in bloom, and that one growing in an area spread its Japanese-like decoration upon the wall. The hedges in the time-worn streets of Fitzroy Square light up—how the green runs along! The spring is more winsome here than in the country. One must be in London to see the spring. In St. John's Wood one can see the spring from afar dancing., haze and sun playing together like a lad with a lass. The sweet air, how tempting it is! and how exciting! It melts on the lips in fond kisses, instilling a delicate gluttony of life; and it would be pleasant to see girls in these gardens walking through shadowy alleys, lit here and there by a ray, to see them walking hand in hand, catching at branches, as girls do when dreaming of lovers. Alas! the gardens are empty of girls, but there are some daffodils! The flower is beautiful in profile, still more beautiful is the starry yellow in full face; and that antique flower carries my mind back—not to Greek times, for the daffodil has lost something of its ancient loveliness, reminding me more of a Wedgewood than a Greek vase."

Now if this be not the arrantest Liberty window-dressing, I know nothing about English prose; which is, of course, quite likely. By "the spring tide", does he mean the spring time, or is it of the Thames he is thinking? "The Japanese-like decoration" is, of course, De Goncourt. Moore went to Paris in the Seventies and Eighties and tried to make out what the Frenchmen were talking about; he caught only their most blatant and least significant accents. "Winsome"—what a word! Sham "blue and white" at four and sixpence a dozen. "One must be in London to see the spring": the cult of the city was the cant of the age: it was a pretty affectation which the dullards worked to death. "Afar dancing . . . like a lad with a lass" (naughty! naughty!). "The sweet air, how tempting it is! and how exciting!" (and oh! but it was sweet!). "Fond kisses . . . girls in the gardens . . . (thirteen, fourteen, maids a-courting) . . . dreaming of lovers". Georgy-porgy, pudding and pie, kissed the girls and made them cry. "Alas! the gardens are empty of girls, but there are some daffodils!" . . . and quelques geraniums . . . We can all do as well if we try.

The Poetry that Mr. Moore Esteems

A FEW pages later, Mr. Moore gives us a taste of his poetic quality. He met her in a cafe, of course; and, of course, she was young and white and interesting and consumptive. And, then, of course, he didn't meet her again; but "the idea of a poem came to me that night ... on the Pont Neuf (of course) . . . the words began to sing together, and I jotted down the first lines before going to bed, and all the next day was passed in composition".

"We are alone! Listen, a little while,

And hear the reason why your weary smile And lute-toned speaking are so very sweet,

And how my love of you is more complete . . ."

That will do. It was not for its own sake, but for the sake of the author's comment, that I dragged the stuff in. It bumps on for a couple of pages at the same jog, the accent falling ever plop on the rhyme, each line conditioned by the necessity of rhyming with the last:

"Of evening, when the air is filled with scent Of blossoms; and my spirits shall be rent The while with many griefs."

It is almost the doggerel of a preparatory school boy who, towards the end of term bursts into song with,

"Three days more, hurrah! hurrah!

And then I shall see my ma."

And what, do you think, is the comment on it of this master of technique? "Great poetry, of course not, but good verse, well turned every line except the penultimate." The penultimate happens not to scan; Mr. Moore has noticed that: his notion of well-turned verse is apparently anything that does. Presumably, his notion of accomplished prose would be prose that was grammatical; judged even by that lenient criterion, his own is far from happy. Such is the vainglorious estimate of his own quality which he reveals with that lauded frankness.

However, the best judges assure me that there is a "childlike beauty" about Mr. Moore's mind. I agree that there is something childish; and begin to think of the mind of a small boy in a low form of a low school who reads what he takes to be naughty books on the sly. Try The End of Marie Pellegrini would you not swear that the author had been brought up on Ranger Gull? This jumble of melodramatic commonplaces was culled surely from surreptitiously studied translations of Nana and Bel Ami. Or is it the glove thrown down by an undergraduate of the Eighties, who has been for a jaunt to Paris and means the public to know it? No; I think, the tragic irony of the whole story, the death-bed scene with the jewels and expensive furniture (presents from the prince), the bitch in pup on the priceless embroidered cushions, the dirty harlots gambling and cheating and squabbling, the bottle of absinthe (of course) on a wonderful Empire table (naturally), and Marie herself dying on the balcony in her brand-new frock while the heartless world enjoys bocks and cigars at the Elys6e Montmartre, all this must surely come of reading Balzac in an abridged translation, when the author ought to have been puzzling over the pons asinorum.

(Continued on page 104)

(Continued, from page 48)

A Redeeming Virtue Detected AND yet I confess I read the Avc, Salve, Vale series with great pleasure; for an explanation of which curious fact I go to one who has explained much that is curious—to Samuel Butler. In that delicious essay The Aunt, the Nieces, and the Dog he gives us merely a handful of illiterate and utterly trivial, but genuine, letters, exchanged between a servant and two maiden ladies. Such documents, he maintains, always make enthralling reading, provided they are authentic records of sufficiently insignificant facts. And he proves it by specimens. In this Irish series, Mr. Moore's good faith is as manifest as his malice—no one would have invented such tittle-tattle. He means to tell the truth, more or less; and he honestly believes in the importance of his subject. What Mr. Hanson or Mr. Tonks said, seems to him as momentous as the sayings of Byron or the Duke. And the result is a book which has precisely the same sort of interest as the correspondence about the dog and the aunt between the housekeeper and the nieces. The Memoirs of My Dead Life (I am thinking of the 1921 edition) lack this charm because for childish vanity we are given a rather vulgar egoism: they are the musings, not of a housekeeper, but of a coxcomb; and the style has been gingered up accordingly. This raffish style is, however, just what is most admired by the genteel public, probably because it smacks most deliciously of La Vie Parisicnnc.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now