Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOur Auction Bridge Refuge

A Sanctuary and Retreat for Persistent, Not to Say Incurable, Bridge Addicts

R. F. FOSTER

Problem XIV

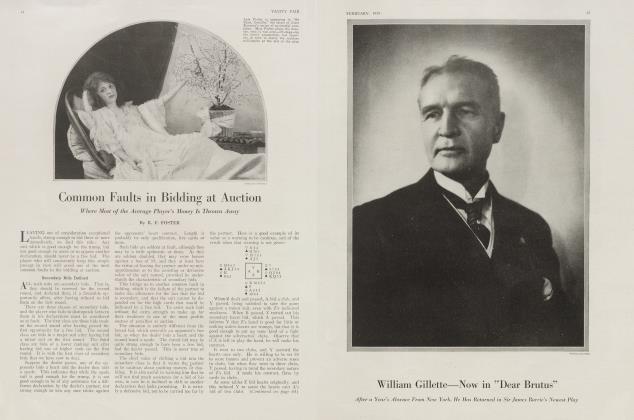

Here is a rather interesting ending, with eight cards remaining in each hand, which has apparently two solutions, but one of them will not get the required number of tricks against the best defence.

There are no trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want four tricks against any defence. How do they get them? Answer in the July Vanity Fair.

A PROPOS of the remark made by a correspondent which was quoted in a recent number of this magazine, to the effect that many of the disasters that were charged up to hard luck were due to bad bidding or play, the following hand was sent from The Elks Club at Glens Falls, N. Y., as likely to be of interest to our readers. It is the first instance I can recall of a suit-bid losing a little slam.

Z dealt and bid no trump, which both A and Y passed. B called two hearts, with the idea of asking a lead against the no-trumper. This is rather forward bidding, not only because it runs the risk of being left with the contract, after overcalling the hand about four tricks, but because there is no reentry for the heart suit, even if it were led and established.

Z doubled. This is the conventional double, to show that the suit bid by the opponents is the one weak spot in an otherwise excellent no-trumper. The answer to the double is for the partner to go back to no-trumps if he can stop the hearts twice, otherwise to bid his suit. Y did neither.

The double being left in, Z led the king of spades. On finding dummy with four, and the position of the queen doubtful, Z shifted to the clubs, leading the king, which held. Then he led a small diamond, which Y won with the ace. Y returned the spade queen, and followed with the ace of clubs and queen of diamonds.

As all these held, Y led a small trump, B playing the queen second hand, and Z winning with the ace. Z led the ace of spades, Y discarding the small diamond. Y had to trump the queen of clubs with the five of hearts and lead a trump. All Y's trumps being in sequence, the only trick B made was the king of hearts.

Asking for a lead against a no-trumper, without the hand to justify it, cost B just 766 points.

Here is a penalty score which I believe is about the record. If any reader of this magazine knows of a single deal in which a player is penalized 1,916 points, I should be glad to see it. This came up in the last game of a rubber at Belleair last March, the score being 18 to 0 against the dealer.

The dealer, Z, started with one no-trump, A bidding two hearts and Y three diamonds. When B went to three hearts, Z thought it a good opportunity to play a little poker and pretend to be afraid of the hearts by assisting the diamonds, bidding four. A, who had sorted his hand wrong, imagining he had five clubs and no spades, the four of spades being among his clubs, went to four hearts and Y to five diamonds, B and Z passing.

Fearing that he would lose the game and rubber if he allowed Y to play the hand at diamonds, A went to five hearts. This Z doubled. Hoping to drive Y back into the diamonds, which he had already bid up to five, A redoubled, but Y did not bite.

Y led the king of diamonds, which held, and followed with a small spade, on which dummy put the nine, Z the jack, and A trumped it, as he still thought he had no spades, and his partner forgot to ask him, as usual. A then led a small trump, thinking to drop them in two leads. Z won the first trump trick with the nine and led two more rounds, so as to exhaust dummy, Y discarding both his clubs.

When Z led the spade queen, A discarded his deuce of clubs. B won with the ace and led another spade, which A trumped with the ten of hearts. Then he led the ten of diamonds, which Y passed up, knowing Z held the ace. Z won the trick with the ace, and pulled A's last trump, returning the jack of diamonds, which Y overtook, making all the rest of the tricks, uncovering A's three revokes at the same time.

On a redoubled contract to win eleven tricks, A wins three only, so he is down 1,600 for that, and 300 for revokes and 16 for simple honors. Can you beat it?

HERE is an anecdote which might amuse the confirmed bridge addict. A certain Mr. Salee prided himself on having read every book on auction, knowing all the laws, and being up on all the modern conventions. He had done so much reading that he had time for very little playing, but was always ready for a rubber.

A five-hour journey was before him. Being unable to get a seat in the Pullman and finding the day coaches very crowded, he concluded to make himself at home in the smoker, although he did not smoke, and had nothing of interest to read.

Two seats ahead of him two well dressed middle aged men had pre-empted a double seat, with a board on their lap and were watching a third man who was canvassing the car for a fourth to make up a game. In answer to his question, "Play bridge?" as he passed up the aisle, Mr. Salee caught the repeated response, "Nope. Pinochle or bid whist." Fearing to lose such an opportunity to while away the time, and also to display his skill, Mr. Salee jumped up and offered his services. He was promptly accepted, and without waiting for the train to start, the game began, the only stakes being the nickel a comer for the brakeman.

They had only one pack of cards supplied by the brakeman, rather dirty, but complete. When Mr. Salee remarked that the laws required two packs to mark the position of the deal, he was told not to worry about the deal. "Any one that gets the deal away from me when it's my turn can have it," as his partner remarked, which called Mr. Salee's attention to the fact that his partner was dealing without any of the usual preliminaries of cutting for partners or seats. The only response to his protest was that if he did not like his partner, he could have either of the others. They could play bridge with any one.

The partner who fell to his lot was a sharp looking, clean shaven man, whom he afterward learned was a leading manufacturer in Hartford. He wore a soft hat, pulled well down over his eyes and had not taken the time to light his cigar, one end of which was rapidly being reduced to a pulp. After sorting his cards with a dexterity born of long practice, he shut them up, tapped the edges on the table, and looking defiantly at the man on his left, announced, "I reserve."

Not knowing exactly what this meant, Mr. Salee waited for the man on his right to declare himself, which he did by passing both the bid and the look of defiance to Mr. Salee. tapping his cards on the table at the same time.

"May I enquire what is meant by the expression, reserve?"

Before the question could be answered, the player on his left said he would pass, adding, "It means that your partner would like to hear from us before he bids. You keep quiet."

(Continued on page 104)

(Continued from page 77)

All four having passed without a bid, Mr. Salee threw down his cards and prepared himself for the next deal.

"Hold on there!" exclaimed the dealer. "I have a bid. I reserved. I'll bid a tiger club." The next player promptly doubled.' Explanations being in order, Mr. Salee was informed that if the dealer reserved, and no one else made a bid, he could start something on the second round. On protesting that he had never heard of such a thing, he was assured that they all played that way in Hartford, and that it was to be. in the new laws, when they came out in January. That being settled, in spite of the fact that he had never read of such a bid in any of the books, he asked the meaning of a tiger club, and was told that tigers, royals, and imperials were worth four times as much as usual, but the penalty for failure was 100, doubled 200, redoubled 400, and that the bidder must hold four honors.

"If I redouble, does it convey any meaning to you?" Mr. Salee asked the dealer.

"Only that you're bluffing, like Mr. Wood here. His partner must take him out. Let him bid. Go to it, Sinclair."

Thus admonished, the fourth hand bid a heart, and before the dealer had time to shift his cigar or take another look at his cards Mr. Wood bid two nullos.

"I think that is a bid out of turn," remarked Mr. Salee, "I elect to cancel it, so that Mr. Sinclair shall take no further part in the bidding." At this astonishing statement, Mr. Sinclair simply beamed on the rest of the table and announced, "We'll see about that. This bidding isn't properly started yet."

"We don't take any notice of those little slips in Hartford," remarked the dealer. "It's my bid. So you are going to bid nullos, are you? Well, I'll just bid two imperial diamonds." The bid being passed, Mr. Salee bid two notrumps, Mr. Sinclair three hearts, the dealer three imperial diamonds, intending, as he afterward explained, to show which was the stronger of his two suits; but Mr. Salee took it as a hint to drop the. no-trumper, and Mr. Sinclair doubled, the dealer redoubling. Mr. Wood led the ace of clubs.

"Well, this is all very irregular," remarked Mr. Salee, as he spread his cards. "According to the laws, the bidding should have stopped when I bid two no-trumps."

"What laws?" inquired Mr. Sinclair, and on being told The Whist Club, the dealer retorted, "What do whist players know about bridge? We play according to Hoyle."

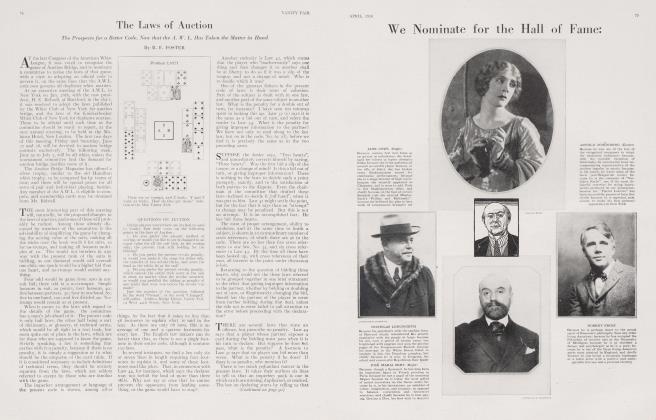

"That's right," agreed Mr. Sinclair. "Shoot again', partner." Thus encouraged, Mr. Wood led another club. This was the distribution:

Having trumped the second , club, three rounds of hearts followed, the dealer discarding his only spade. Another club trumped by dummy and over-trumped, allowed the dealer to trump the next heart with the ten, overtaken by the jack, and one more club fell to Mr. Sinclair's trumps. Eight tricks, promptly scored as 1,544 for the Sinclair and Wood end of it.

"I don't think you played that hand very well, partner," remarked Mr. Salee. "The first four tricks, are, of course, not to be helped; but if you trump the third heart with the queen, you make your contract, and win, I really don't know how many points, on imperial, I think you call them, diamonds redoubled. If you had left me alone, or rather assisted my no-trump bid, I could have made four odd easily."

"Then why don't you bid it yourself?" was the prompt rejoinder. "I reserve the first bid, showing I've got a good bid in my hand, but am in the .high grass to kill anything they call. Then I show you four honors in two suits, and you have both the other suits stopped. If you paid a little more attention to the game and not so much to-the laws, we might win something."

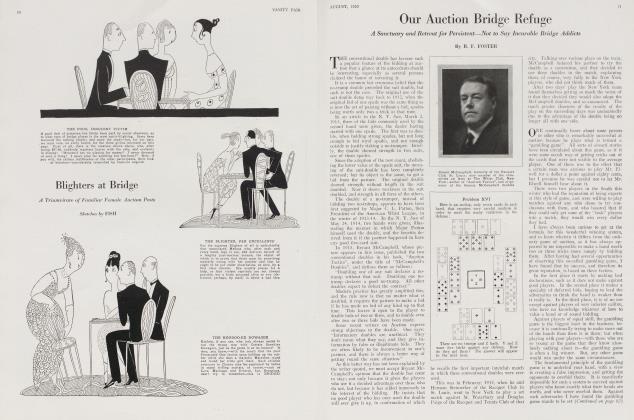

Answer to the May Problem

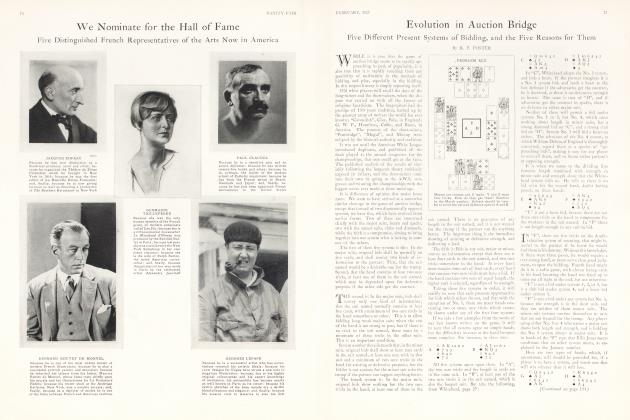

THIS was the distribution of the cards in Harry Boardman's problem, XIII, which appeared in the last number of this magazine. These problems of ours are becoming increasingly popular and the inquiries engendered by them are coming to us from all parts of the world.

There are no trumps and Z leads. Y and Z want five tricks against any defence. This is how they get them:

Z leads the nine of clubs, which Y wins with the queen. Y returns the queen of diamonds, putting the lead into A's hand, and giving that player the choice of two continuations.

If A leads a small heart, Y discards a diamond, Z winning the trick and leading the ten of diamonds, upon which Y forthwith discards the ten of clubs. Now Z can put B in the lead with the losing club, and Y makes two spade tricks.

If A leads a spade instead of a heart at the third trick, Y just covers whichever card A leads, and Z discards a heart Supposing B to win this trick with the ace of spades, he will lead a diamond, which Z wins with the ten, leading the queen of hearts, on which

Y discards a small spade. Now Z must make two heart tricks, or Y makes two spades, according to A's play on the heart queen, the club ten being good either way.

If B leads a club, instead of the diamond, after winning the spade trick, A will discard a heart and Y will lead the diamond. Now A must discard a heart again, or lose all his spades. Z wins the diamond trick and puts A in with the heart, so that Y shall make two tricks in spades.

B may refuse to win the spade trick, in which case Y holds it with whichever card he played to cover A's lead. Y then leads the diamond, which, naturally, Z wins, leading back the queen of hearts, upon which Y will discard a spade. Now if A leads another spade, Y covers and B wins with the ace; but he loses a trick in each of the black suits to Y.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now