Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLimón's New Twist

DANCE

Thomas Connors

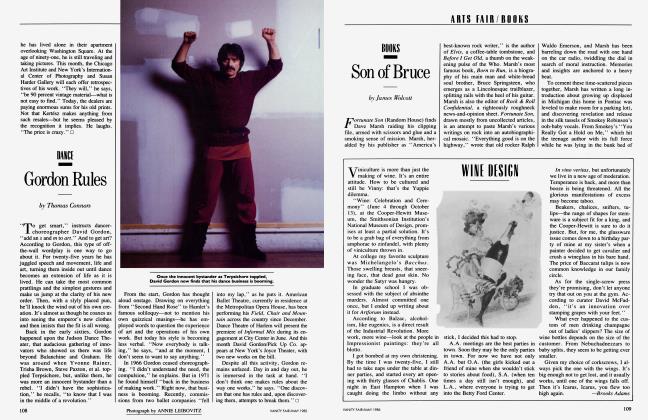

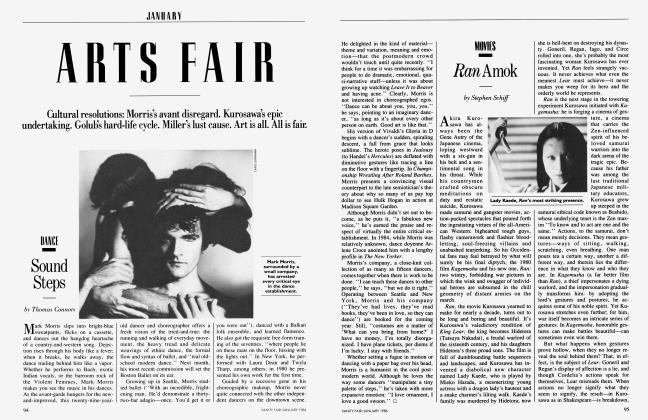

Lutz Forster doesn't look like the average dancer. He's taller and thinner than most, with a profile to rival Aaron Copland's; it's no wonder Pina Bausch—famous for picking offbeat performers—made him a member of her company ten years ago. With Bausch, whose acclaimed Wuppertaler Tanztheater brought Sturm und Drang up to date, Forster has sat calmly in his underwear while getting a hotfoot, walked through theaters offering tea to bewildered audiences, and danced so convincingly en travesti to Kurt Weill you'd have thought he understudied Sally Bowles. With such a curriculum vitae, it may seem odd that this thoroughly German artist has been named principal dancer and associate artistic director of the Jose Limon Dance Company, a major modem ensemble where American themes know no borders. But, for Forster, it's become a home away from home.

At the university in Hamburg, Forster studied Russian, French, and history. He took dance class once a week, but as "a hobby, nothing to take seriously." Avocation became vocation, and at twenty-one Forster entered the famed Folkwangschule in Essen, in 1973. While he mastered new German dance, he looked to Limon for ''something missing in my personal dance history." In 1981 he arrived in New York on a scholarship with the Limon company, and began performing between appearances with Bausch.

Jose Limon, who died in 1972, came of age in the golden days of American modem dance. His Mexican machismo had once compelled him to dismiss dance as a distinctly feminine enterprise, but a performance by the German expressionist dancer Harald Kreutzberg changed his mind. Suddenly he saw ''a vision of ineffable power . . . dance as Michelangelo's visions dance and as the music of Bach dances." With Limon's death, his company hit hard times. ''It was difficult to do more than just survive," recalls artistic director Carla Maxwell, a member since 1965. ''We couldn't go on doing just what we were doing; we were stagnating. Lutz has made a major transition possible."

Observers who find contemporary German dance a gross symptom of postwar angst may regard Forster's association with Limon's exalted sentiments a case of recombinant aesthetics. But to Forster, who was appointed in 1984, "the point of departure is the same: trying to find out something about people." Maxwell concurs: ''You can't hide in [Limon's] work; you can't hide in the kind of work Lutz has done. I think we're after the same kind of theater."

This season, Forster has invited his former teacher Jean Cebron to mount three works on the twelve-member company and has commissioned a piece from Susanne Linke, who also performed with Bausch. These new works, Forster's first artistic ventures, will be seen at the Joyce Theater this month during the company's first appearance in New York in three years. Forster himself will dance in Limon's masterpiece The Moor s Pavane, as well as in Anna Sokolow's Rooms and Meredith Monk's Break.

As for Forster, "I think tradition is something wonderful. So few things are originally American. Modem dance is one of them, and I don't understand why there isn't more interest—not in creating museums of dance, but in creating something new from this base."

While the Limon repertory may fit Forster like a second skin, he's well aware that it may not be fashionable in a dance world where drama and feeling are virtually verboten. ''Somehow, people have become very afraid of emotion. But as long as we haven't gotten to a time where robots are dancing, I want to see people onstage." Looking ahead, he remains cautious, yet optimistic. "I don't want to go shopping for choreographers. Some kind of continuity would be nice. I hope we can develop relationships with Jean, Susanne, and Meredith. And then perhaps me."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now