Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBauhaus Revisited

Thomas Connors

ARTS FAIR

Mack sets his sites. Sherman gives up her ghosts. Tipton hits the switch. Streep carries Plenty. Sneed backtracks. Art is all. All is fair.

DANCE

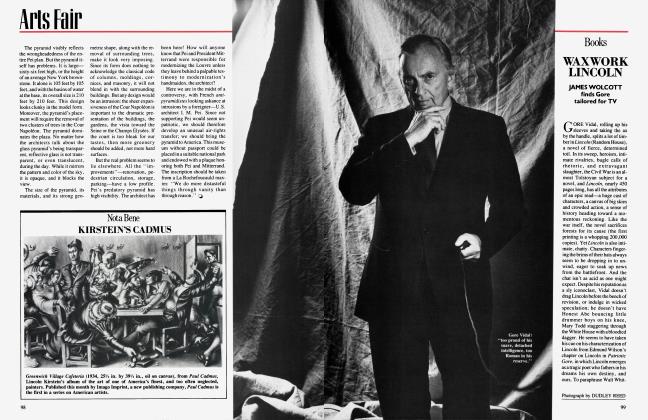

History threw Oskar Schlemmer (1888— 1943) a mean curve; for years, his achievements were overshadowed by those of his fellow Bauhaus-mates. But no longer. In this age of performance art and postmodern dance, people are giving the German designerdirectorchoreographerpainter a second look. This month, in conjunction with New York's Museum of Modern Art's exhibition "Contrasts of Form," the Joyce Theater is presenting a re-creation of Schlemmer's 1922 Triadic Ballet from the Academy of Arts in Berlin. And in February the Baltimore Museum of Art will mount a multimedia show of his work.

At the Bauhaus, that cathedral of new faith in art and technology, Schlemmer was the errant choirboy, peeking under ecclesiastical robes. Not that he wasn't serious, but he put a premium on playfulness. A lover of puppets, variety shows, and the circus, Schlemmer drew much of the inspiration for his theater from the famous Bauhaus parties. At the same time, he was a rigorous theoretician, shuffling Aristotle's dramatic unities like a cardsharp and analyzing the theater like a latter-day Euclid.

While his associates— Marcel Breuer, Walter Gropius—proclaimed their ideas in glass and steel, Schlemmer chose to work with lighter stuff: space and time, with the human figure as cynosure. During his abbreviated Bauhaus career, Schlemmer created more than a dozen ballets, three-dimensional realizations of constructivist principles. The dancer was the medium, conducting and defining the unseen coordinates within the frame of the stage. And in the dances themselves—simple and mundane, with neither plot nor emotional connotations—Schlemmer thumbed his nose at current theatrical conventions.

The Triadic Ballet consisted of twelve dances arranged in three parts (with Schlemmer among the three performers). The eighteen sculptural costumes—with their bulky padding, metal rings, rigid planes, and spirals—simultaneously concealed and accentuated the human form, restricting the dancers' movements. However, Schlemmer's intention was not to dehumanize but rather to isolate the pure, abstract geometry of the figure in space.

A year after the Triadic Ballet's last performance in Paris in 1932, the Nazis pulled the plug on the Bauhaus. While many of his colleagues moved on to cushy university chairs and big commissions in America, Schlemmer stayed behind, an artistic P.O.W. in his own country, barred from teaching and performing.

In 1977, Dirk Scheper, head of the department of performing arts at Berlin's Academy of Arts, brought the stage version of Schlemmer's Triadic Ballet back to life. He had nine costumes reconstructed from originals stored in Stuttgart, and the rest from sketches and photographs. He asked choreographer Gerhard Bohner to reimagine the forgotten dance pieces, and the work found a ready audience— mostly painters and architects. "The few dance people who came to see it," says Scheper, "thought it was funny that this is called a dance." Yet for all its conceptual underpinnings and its defiance of categorization, it reinforces the Schlemmer credo: "Not the machine, not abstract—Man always." Audiences take to it. "I see people leaving the theater," reports Scheper, "being amused and looking lucky."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now