Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowImportance of the Play in Contract Bridge

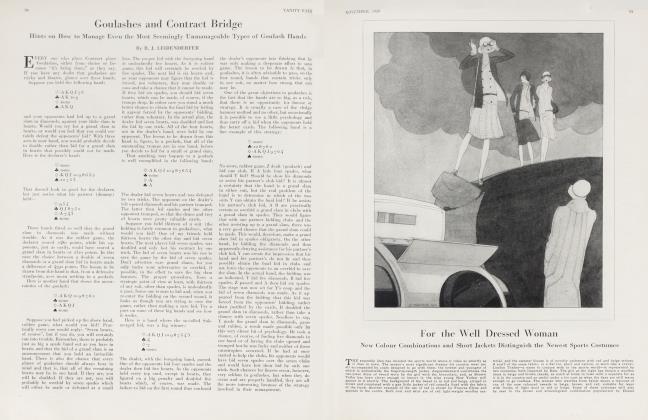

Showing That the Correct Play of the Hands Is More Important in Contract Than in Auction

R. J. LEIBENDERFER

IF there is one thing in auction that must be incorporated into contract and polished up and improved to the nth degree, it is the play of the hands. At auction there is always the incentive to score a game or a slam, but not the necessity for it that there so often is in contract. Games are frequently bid for in auction, but not more than half as often as in contract. The bidding for a slam in auction, is almost unheard of, while at contract it is a not unusual thing at all.

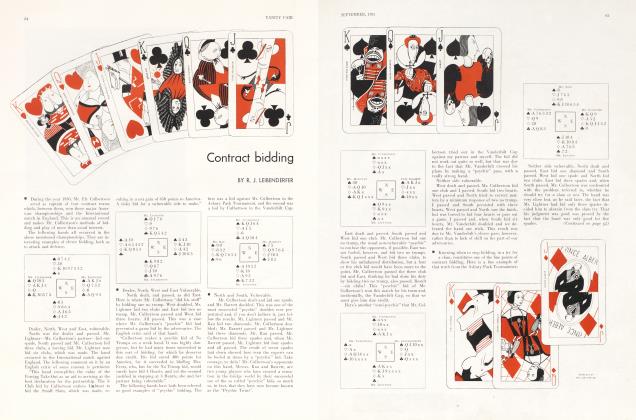

As a result of this it becomes much more important to play the hand so well that the game or slam that has been bid can actually be made. The player who can figure out the only way to score the game or slam that are so important at contract is the player who is going to shine as one of the new galaxy of contract stars now in the making. The bidding at contract is important, of course, but its ratio of importance to the play of the hand, is considerably less than it is in auction. Most authorities seem to agree that, in auction, the bidding is more important than the play in the ratio of about two to one. At contract, however, the play of the hands is just as important as the bidding, if not more so. Of what good is a daring try for a game or a slam if the play is not equal to the task. The answer is obvious, so don't set yourself or your partner a greater task by your bidding than you or he can carry through to a successful conclusion by your play. The following hands are interesting in that accurate bidding set a task that only still more accurate play was able to accomplish. The first of them was as follows: No score, rubber game. Z dealt and passed. A passed, Y bids two spades and B passed. Z bids four clubs, A passed, Y bid four diamonds and B passed. Z now bid six clubs and all passed. This bid for a slam by Z is very questionable, but his doubtful bid was more than offset by his clever play.

The Play: A led the ace of hearts and followed with the five of clubs. Y followed suit and, of course, B played the deuce so Z was forced in the lead at the second trick. He now had to figure out a way to capture B's king of clubs or the slam so daringly bid for could not be made. The only way to accomplish this result is by shortening his trumps in such a way that Y will be in the lead at the twelfth trick and so give Z a tenace position over B's king of clubs. To do this, Z must trump at least three of Y's winning cards and thus make the so-called "Grand Coup" three times. It is very seldom that a player has the opportunity to make the Grand Coup even once, so that the chance to do so three times in one hand, the "Triple Grand Coup", is an event of the greatest interest. At trick three, Z should lead the nine of spades and win the trick in Y's hand with the jack. Y should now lead the queen of spades and Z should trump in his hand with the eight of clubs (Grand Coup No. 1). Z should now lead the deuce of diamonds, winning the trick in Y's hand with the queen.

Y should now lead the king of spades and Z should trump in his hand with the nine of clubs (Grand Coup No. 2). Z should now lead the seven of diamonds, winning the trick in Y's hand with the king. Y should now lead the ace of diamonds and Z should trump in his hand with the ten of clubs (Grand Coup No. 3). Z should now lead the five of hearts and win the trick in Y's hand with the queen. Y should now lead the five of diamonds and Z should trump in his hand with the jack of trumps. (This play does not constitute a Grand Coup because it is trumping a losing trick, not a winning one.) Z should now lead his last heart and win the trick in Y's hand with the king. Now, no matter what Y plays, Z must win the last two tricks as he has left in his hand the ace, queen of clubs and B has left the king, six of clubs. In other words,

Y is in the lead at the twelfth trick and Z has shortened his trump holding by trumping three of Y's winning tricks and one loser. In this way he is able to shut out B's king of clubs and so score the small slam in clubs, a perfect combination of daring bidding and brilliant play.

Here is another interesting hand:

No score, rubber game. Z dealt and bid one diamond. This bid may seem peculiar to the average player, but the expert knows that a hand of this type, containing three four card suits and a singleton, plays much better at a suit bid than at no trumps. For that reason, Z started qff with a diamond bid but with the firm intention of showing the other two suits if the opportunity offered. A passed and Y bid two diamonds. B passed and Z now bid two spades. A passed and Y correctly bid three spades. When B passed, Z bid four spades and all passed.

The Play: A opened the eight of hearts and B won the trick with the ace. He has several possible plays, (a) to return his partner's heart lead and thus force Y to trump or (b) to lead a club or (c)to lead a spade. In this case, B elected to lead the deuce of clubs and Z won the trick with the ace. Z hasn't much choice but to lead a heart and trump in Y's hand with the trey of spades. His next play is also forced to some extent by his desire to obtain the lead in his own hand, if possible. Y should therefore lead the queen of diamonds. B should cover and Z should win the trick with the ace. He should now lead the ten of hearts and trump in Y's hand with the six of spades. It is at this stage that the hand becomes interesting and Z must use considerable thought. His best play now is the ace of spades, on which all follow suit. The queen of clubs should now be played and, when B does not cover, Z should discard the queen of hearts. A wins this trick and can lead either a heart, a club or a diamond, but his play, is immaterial. The heart is really the best play as it forces Z to trump with the eight of trumps. Z should now lead the deuce of diamonds, winning the trick in Y's hand with the jack. Y should now lead the jack of clubs and Z should discard the five of diamonds. Y should now lead the trey of diamonds, B should discard his last club and A wins the trick with the ten. No matter what A now leads, Z must win the next two tricks, thus scoring game and rubber. The play actually took place as given and Z's partner, after the hand, said: "Partner, the way you played that hand made me dizzy. I never saw anybody shift the play to so many different suits". It was a well played hand and shows the necessity of adapting your play not only to the cards held but also to the play of your adversaries.

Here is an interesting grand slam hand: No score, rubber game. Z, the dealer, bid two no trump. A passed, Y bid five diamonds and B passed. Z now bid five spades, A passed and Y correctly bid six no trump. When B passed, Z had the chance that comes so seldom and had the courage to take advantage of it, so bid seven no trump. All passed and A opened the seven of clubs on which Y played the eight, B the five and Y the deuce. Y now led the eight of spades. B played the deuce, Z played the jack and A played the trey. Assuming that A's lead is fourth best and therefore marks A with the king of clubs and that B is marked with the king of spades, how should Z plan the subsequent play of the hand so that he can make the Grand Slam against any defense or distribution of the remaining cards?

(Continued on page 104)

(Continued from page 70)

Solution: At the third trick, Z should lead the ace of diamonds and follow with the ten, winning the trick in Y's (Dummy's) hand with the jack. Y should now lead three rounds of diamonds on which Z should discard the ten of clubs and the seven and nine of spades. The discards of A and B are immaterial as will be shown later. Y should then lead the four of clubs, winning the trick in Z's hand with the ace. Z should then lead the ace of spades and discard the six of clubs from Y's hand. Z should now lead the deuce of hearts and win the trick in Y's hand with the king. Y should now lead his last diamond trick, the eleventh trick. On this trick B is forced to discard. He cannot discard the king of spades or Z's queen will be good, so is forced to discard a heart. He is thus left with the king of spades and one heart. Z can now discard the queen of spades and is thus left with the ace and trey of hearts. A is also forced to discard. He cannot discard the king of clubs or Y's queen of clubs will be good so A also is forced to discard a heart, and is thus left with the king of clubs and one heart. At the twelfth trick, therefore, Y should lead the eight of hearts and Z with the ace, trey, must win the last two tricks, irrespective of the original distribution of the hearts. This is a fine illustration of the double squeeze and is a hand taken from actual play.

These hands may help contract players to see that skill at playing the cards is just as important as a mastery of correct bidding. Brush up on your play or you will miss many a game and slam at contract.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now