Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowGoulashes and Contract Bridge

Hints on How to Manage Even the Most Seemingly Unmanageable Types of Goulash Hands

R. J. LEIBENDERFER

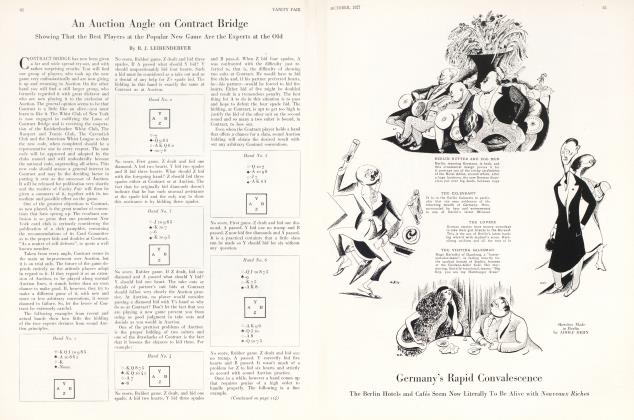

EVERY one who plays Contract plays Goulashes, either from choice or because "it's being done," as they say. If you have any doubt that goulashes are tricky and bizarre, glance over these hands. Suppose you held the following hand:

and your opponents had bid up to a grand slam in diamonds, against your little slam in hearts. Would you try for a grand slam in hearts, or would you feel that you could certainly defeat the opponents' bid? With three aces in your hand, you would probably decide to double rather than bid for a grand slam in hearts that possibly could not be made. Here is the declarer's hand:

That doesn't look so good for the declarer, hut just notice what his partner (dummy) held—

These hands fitted so well that the grand slam in diamonds was made without trouble. As it was the rubber game, the declarer scored 2480 points, while his opponents, just as easily, could have scored a grand slam in hearts or 2310 points. In this case the choice between a double of seven diamonds or a grand slam bid in hearts made a difference of 4790 points. The lesson to be drawn from this hand is that, from a defensive standpoint, aces mean nothing in a goulash.

Here is another hand that shows the uncertainties of the goulash:

Suppose you had picked up the above hand, rubber game, what would you bid? Practically every one would reply: "Seven hearts, of course", but if you do, you will certainly run into trouble. Remember, there is probably just as big a spade hand out as you have in hearts and that the bid of a grand slam is an announcement that you hold an invincible hand. There is also the chance that every player of goulashes should always bear in mind and that is, that all of the remaining hearts may be in one hand. If they are, you will be doubled. If they are not, you will probably be overbid by seven spades which will either be made or defeated at a small

loss. The proper bid with the foregoing hand is undoubtedly five hearts. As it is rubber game, this bid will certainly be overbid by five spades. The next bid is six hearts and, as your opponents may figure that the bid is forced, not voluntary, they may double or pass and take a chance that it cannot be made. If they bid six spades, you should bid seven hearts, which can be made, of course, if the trumps drop. In either case you stand a much better chance to obtain the final bid by letting it appear forced by the opponents' bidding, rather than voluntary. In the actual play, the dealer bid seven hearts, was doubled and lost the bid by one trick. All of the four hearts, not in the dealer's hand, were held by one opponent. The lesson to be drawn from this hand is, figure, in a goulash, that all of the outstanding trumps are in one hand, before you decide to bid for a small or grand slam.

That anything may happen to a goulash is well exemplified in the following hand:

The dealer bid seven hearts and was defeated by two tricks. The opponent on the dealer's left opened diamonds and his partner trumped. The latter then led spades and the other opponent trumped, so that the deuce and trey of hearts were pretty valuable cards.

Suppose you held thirteen of a suit (the holding is fairly common in goulashe.s), what would you bid? One of my friends held thirteen hearts the other day and bid seven hearts. The next player bid seven spades, was doubled and only lost his contract by one trick. The bid of seven hearts was his cue to save the game by the bid of seven spades. Don't advertise sure grand slams, for you only incite your adversaries to overbid, if possible, in the effort to save the big slam bonuses. The proper procedure, from a strategic point of view at least, with thirteen of any suit, other than spades, is undoubtedly a pass. Some one is sure to bid and, when you re-enter the bidding on the second round, it looks as though you are trying to save the game, rather than making a sure bid. Try a pass on some of these big hands and see how it works.

Here is a hand where the so-called Submerged bid, was a big winner:

The dealer, with the foregoing hand, passed. One of the opponents bid four spades and the dealer then bid five hearts. As the opponents held every top card, except in hearts, they figured on a big penalty and doubled five hearts which, of course, was made. The failure to bid on the first round thus confused

the dealer's opponents into thinking that he was only making a desperate effort to save game. The lesson to be drawn is that, in goulashes, it is often advisable to pass, on the first round, hands that contain tricks only in one suit, no matter how strong that suit may be.

One of the great objections to goulashes is the fact that the hands are so big, as a rule, that there is no opportunity for finesse or strategy. It is usually a case of the sledge hammer method and no other, but occasionally it is possible to use a little psychology and thus carry off a bid when the opponents hold the better cards. The following hand is a fine example of this strategy:

No score, rubber game. Z dealt (goulash) and bid one club. If A bids four spades, what should Y bid? Should he show his diamonds or assist his partner's club bid? It is almost a certainty that the hand is a grand slam in either suit, but the real problem of the hand is to determine in which of the two suits Y can obtain the final bid? If he assists his partner's club bid, A B are practically certain to overbid a grand slam in clubs with a grand slam in spades. They would figure that with one partner bidding clubs and the other assisting up to a grand slam, there was a very good chance that the grand slam could be made. This would, therefore, make a grand slam bid in spades obligatory. On the other hand, by bidding five diamonds and thus apparently denying assistance for his partner's club bid, Y can create the impression that his hand and his partner's do not fit and thus possibly obtain the final bid in clubs and not force the opponents to an overbid to save the slam. In the actual hand, the bidding was as indicated. Y bid five diamonds, B bid five spades, Z passed and A then bid six spades. The stage was now set for Y's coup and the bid of seven diamonds was made. As it appeared from the bidding that this bid was forced from the opponents' bidding, rather than justified by the cards, B doubled the grand slam in diamonds, rather than take a chance with seven spades. Needless to say, Y made the grand slam in diamonds, game and rubber, a result made possible only by this very clever bit of psychology. He took a chance, of course, of finding five diamonds in one hand or of having the clubs opened and trumped but he was lucky and neither of these catastrophes occurred. If he had at once started to help the clubs, his opponents would have bid seven spades over the seven clubs and would have lost their bid by only one trick. Such chances for finesse occur, however, very seldom in goulashes, but when they do occur and are properly handled, they are all the more interesting because of the strategy involved in their management.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now