Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWhy I Love France

By an American Who, Despite the Fashion, Acknowledges the American Debt

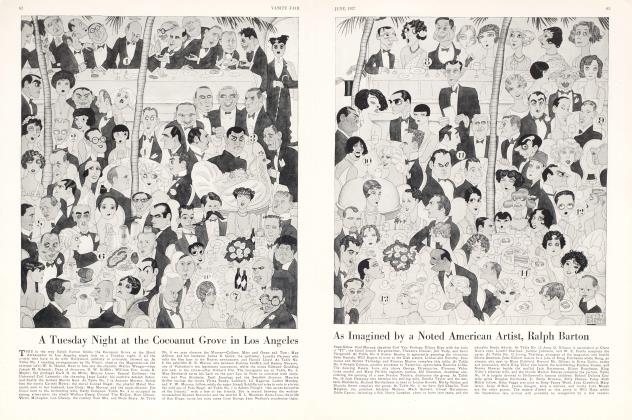

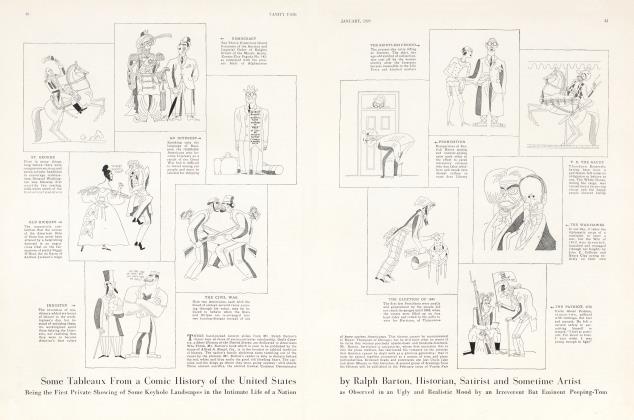

RALPH BARTON

IN THE stagnant days before the War when we could consider the problem of race prejudice without feeling moved to Do Something About It, one of the End Men in Lew Dockstader's Minstrels used to stop the show by shouting over the clatter of his melodious bones, "Come in heah, Rastus, and quit playin' wid dose white boys! Dey lick de 'lasses off yo' bread and den dey call yo' a niggah!"

I used to laugh at that when I was young and cruel. Today I regard the joke as a bitter indictment of the human race for its ingratitude and its bad manners, for now the 'lasses has been licked from French bread and it is America that is calling France out of its name. As a Francophile—no, let me confess it at once— as a love blinded, gibbering, hysterical Francomaniac of long standing, I look upon the present deplorable disaccord between France and America as the greatest calamity produced by the World War. Perhaps, if I thoroughly understood the international debt situation, or even if I felt that I ought to pretend that I did, I might conceivably (I am being very large) harbour some sort of grudge against the French ; but, as matters stand, I can not lose sight of the fact that I do not, myself, particularly enjoy the first of the month, that I am inclined to regard my income tax as an insufferable imposition and that I meet notes at the bank with such singularly bad grace that the very meanest behaviour on the part of any debtor would excite my sympathy rather than my indignation.

If it is true, and I suppose, from a pawnbroker's point of view, it is true, that France owes us a few rubbishy dollars, borrowed from us to pay our own profiteers for dud shells stamped out in converted chandelier factories at a time when she was too busy winning the war to count the change or check the goods, then our debt to France for the example of her magnificent history, her consummate civilization and her superb mistakes is incalculable. Rendered diffident by the withering cynicism of our bill-collecting and hard boiled statesmen, I would not presume to contend that France's example possesses a market value in money, nor would I have the courage to attempt to make of it an argument in favor of the cancellation of the debt. I merely feel, in my maudlin way, that the civilization with which France has dowered us is worth more than money, and that, indeed,life wouldhardly be worth living at all in these late English colonies without the enrichment and the flavour which we have borrowed for it from the French.

This statement will sound shockingly unpatriotic only to those who have never stopped to consider what an abundance of fair things France has bestowed upon us, or to ask themselves how, now that we possess them, we should ever get on without them. It is a harrowing, but a fruitful experiment to imagine all that is French or that ever has been French suddenly extracted from our life, and to contemplate the resulting wreckage. Would we not find ourselves existing in a bleak and primitive culture—a plucked skeleton of a civilization: The tyranny of our Babylonian architecture would be unrelieved by an occasional glimpse of a French window, a Mansard roof or a graceful Renaissance grill. Our women, stripped of the creations of the rue de la Paix, would have to scurry for Mother Hubbards and replace the subtle allure of French perfumes with indigenous Lily of the Valley. With France erased from history, the Norman Conquest would never have taken place and our language, at one blow, would be robbed of practically all its words relating to art and higher culture, the figurative terms of poetry and the idiom of gentility, of courtesy and of elegance.

Picture, if you can bear it, a world without champagne! A stricken planet guzzling gin and Scotch and vodka and other barbarous fire-waters, not possessing the genius to turn its grapes into Burgundy, or Bordeaux or Vouvray,struggling along in ignorance of such refinements as Château Yquem, Château Lafite, Pape Clement, Chamber tin, Romanee-Conti, Clos-d-Vougeot; existing without the tender aid of the Houses of G.. sl. r [(The alarming scarcity of this king of champagnes, especially in its best year, 1911, makes the withholding of its name from such a group of gourmets as constitute the readers of Vanity Fair a cannv precaution.)], Veuve Clicquot, Mumm, and Pommery & Greno; deprived of the alchemy of the monastery of Chartreuse! A de-Gallicized people would drink by capacity, knowing nothing of the fine art and science of drinking, of intelligently delighting the eye, the nose and the finger tips as well as the gullet, of respectfully rendering to a great wine its proper glass and culinary accompaniment.

And here, the mention of the art of the royal maître d'hôtel, Béchamel, makes his contemplation of a French-less world almost too painful to continue. Subtract from this life here below French cooking, and you have left —grub. In the place of foul aide de Bresse truffée á la périgour dine, you have a wet frankfurter; without selle de Pauillac à la française, you may gnaw at fried beefsteak; for filets de sole Marguery, substitute boiled cod-fish, and for crepes Suzette, flapjacks. Imagine, with what fortitude you can conjure up, the loss of soufe a Poignon, bouillabaisse Marseillaise, caneton à la presse, coqau vin, poulet roti à la crème, poulet sauté Côte d'Azur, langouste, pâé de foie gras de Strasbourg, pommes de terre souffées, Bar-le-Duc, of a dozen cheeses, a score of fruits, a hundred vegetables, a thousand sauces and ten thousand miraculous dishes conceived and prepared by a race of master cooks, who, like the Grand Conde's chef, Vatel, are ready to slay themselves for the honor and dignity of their calling. In the history of France the names of great cooks survive from remoter periods than the names of great poets, and kings and cardinals boast of having invented sauces. Today, French cookery completely dominates the kitchens of the world and the French chef, crowned with starched linen and enthroned amid glowing coppers, sits in Paris, supreme dictator of the civilized palate.

Although a bare thirtieth of the world's population speaks the French language (as against an English-speaking tenth, a German-speaking fifteenth and a Russian-speaking twentieth) French literature takes its place, if not at the same lonely height of glory occupied by French cooking, certainly in the first rank of the literatures of the world. From the Chanson de Roland through a long and imposing list of great writers, French letters have set a noble pace and their loss would be disastrous. Villon, Rabelais, Montaigne, Pascal, Roche-foucauld, la Fontaine, Perrault, Corneille, Molière, Racine, Fénelon, Saint-Simon, Voltaire, Buffon, Rousseau, Beaumarchais, Lamartine, de Musset, Mallarmé, Stendhal, Mérimec, Baudelaire, Gautier, Hugo, Dumas, the giants Balzac and Flaubert, the Goncourts, Zola, Maupassant, Renan, Taine, France, Loti, Vérlaine, Rostand, and the post-war Proust, Duhamel, Romain, Cocteau, Valéry, MacOrlan, Maurois, Morand and the Comtesse de Noailles—such names shine as stars of the first magnitude in the firmament of the world's literature. In the field of painting the French again rise to preëminent heights. Here they count as the saviours of a dying art. Painting had lain on her deathbed for a century, gasping her last, when the Frenchmen Poussin, Courbet, Ingres, Degas, Renoir, Manet, Monet, Cézanne, Rousseau, Seurat, Forain, Moreau, Toulouse-Lautrec, Redon, Matisse and the naturalized Van Gogh and Picasso applied the pulmotor to the venerable old girl and sent us all flying to the galleries to look, or to our easels to try again. Modern music is almost completely in the hands of the French and Paris inspires the lutes of the world.

Continued on page 100

Continued from page 60

With France counted out, medicine, astronomy, chemistry, invention and science in general would be hopelessly crippled. Germs and radium, smokeless-powder, electric steel and the photograph would have to be discovered all over again and we would not know how to Pasteurize our milk. Deprived of the pioneer discoveries of E. J. Marey and Louis Lumière, we should even have to get along somehow without motion pictures.

We would, of course, without these glories of France, still have Beethoven and golf, but—and this would be the greatest loss of all—we would not have the French as professors in the art and mystery of living. They know, as no other people on earth knows, how to live, and it is this great gift that fills their country with foreigners every year.

Last summer no fewer than 220,000 Americans, obeying their finer urges, went to France. While they were gone, the newspapers of this country decided, for some unexplained reason, to convince their public that American tourists were being insulted and attacked in the streets of Paris. As an American tourist in Paris during the months between March and October I did not see or hear, directly or indirectly, of any such occurrences as were reported in the newspapers and I can only suppose that they were marking time until the Browning case opened. On the other hand, it must be confessed with shame, that the tourists furnish almost hourly provocation for assault—for lynching, very often. They are inclined to look on Paris as a vast and glorified Coney Island and they shed their inhibitions as they enter. Surrounded by a people whose language they do not understand, they feel themselves somehow hidden by the fact and invisible to the natives. They behave accordingly. Dignified old gentlemen get magnificiently boiled in public bars and the young go in exclusively for pranks that would land them in jail at home. The male tourist, as a rule, has learned about France from the burlesque theatres and the funny papers and he vaguely expects to be met at the Gare St.-Lazare by a bevy of beautiful chorus girls who speak English with a cute French accent and possess loose morals. He feels cheated and disappointed to find that the women he sees most of in Paris, namely, concierges, chambermaids, charwomen and the bedraggled ladies about the Cafés du Dome and de la Rotonde are generally strikingly plain and excessively straight-laced. The female tourist looks on the words libertine and Frenchman as synonyms and moves about Paris armed to the teeth against amorous attack, little dreaming that she is shocking the French beyond expression with her knees and her habit of lounging when she sits down.

Far from hating us, as our newspapers and misunderstood tourists would have us believe they do, the French are rather inclined to grin and bear us and to serve up Paris to us at, heaven knows, a mean enough price. They are an intelligently curious race and they try very hard to understand us. They learn English to this end and we suffer from a national inaptitude for languages, and it is to this fact, I think, that all our mutual misunderstandings can be traced. English, because it is the language of the dollar and the pound, and because it is a good language, will eventually force itself upon the world as the universal tongue, but until this happy day arrives, the American who does not take the trouble to learn French can not know France. Once an American does learn French and by this I mean French that will work across a dinner table and not the French that we inflict on waiters and taxi-drivers and scatter in jewelled phrases throughout our sterner idiom—he discovers to his amazement and joy that a Parisian is a New Yorker who waves his arms a little when he talks about investments and a Lyonnais is a Chicagoan with a moustache. For, fundamentally, there is a sympathy between the two races. We have the same desires and ambitions, the same faults and the same childish outlook on life in general.

This summer, another army of tourists will invade that green and pleasant land of France. They will sit in restaurants and cafes which are never visited by the native French, sighing for home and candied sweet potatoes. Embarrassed by the language, they will be unintentionally very rude to waiters, wine-butlers, taxi-drivers, hotel employees and policemen, who, chiefly, will bear the shock of the American invasion.

The French, on their part, will tend them and feed them, support them when they are too drunk to stand alone, and send them home happier and richer by an impression of the outside world and, perhaps even, better Americans for being only 99/4%.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now