Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEducating an Author

Some Highly Valuable Hints for Those Afflicted With the Guilty Urge to Write

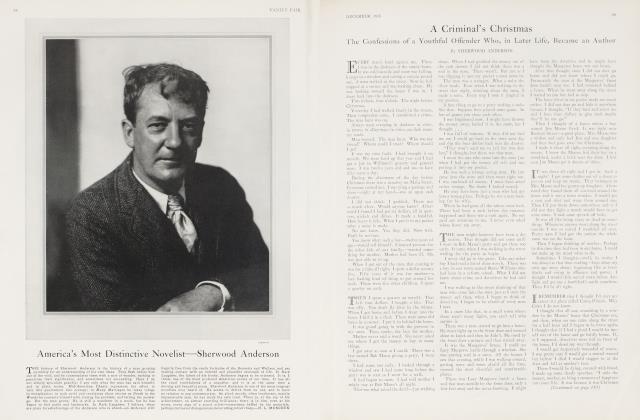

SHERWOOD ANDERSON

THIS is a subject on which I have long wanted to write. With what eagerness I about my task. Writing of authorship will of course enable me to write of authors, and I think authors are such wonderful beings.

I am one myself. People who do not know authors personally, never realize what charming, highly cultured people they are. Years ago, when I was myself not an author, I used to go into restaurants where authors sat. There they were—perhaps four or five of them—sitting at a table. Almost without exception their heads were beautifully shaped. I always thought they had such expressive hands. Of course, I could not hear their conversation although occasionally, even in those days, I did venture to walk past such a table. I pretended to be looking for my hat. Sometimes I caught a word or two. What golden words!

Before I myself became an author, I used to go about thinking that my desire to see my name on the printed page was peculiar to myself. I never dreamed anyone else had it. In those days I had many thoughts and impulses I was very sure were peculiar to myself.

FOR example, let us suppose that I am walking in the street. There is a tall and very beautiful building, by a bridge. I may have passed the bridge dozens of times before, but on the particular occasion of which I am now thinking, something led me to look closely at it. Perhaps the sun was just going down in a mass of gray smoke behind the building. Until that moment I had always thought of it as being white. Suddenly it became rosy red, it became blue, it became purple.

I had discovered that the building was beautiful and was very sure that of all the thousands of people who passed it daily, I was the only one who ever had made the discovery. I looked about me resentfully. It was evening and people were going home to dine. Men were driving trucks. They were hurrying to catch street-cars. What stupid men, I thought.

You will understand that all this occurred before I became an author and began to associate with other authors. Sometimes, nowadays, when I am in France, San Francisco, New Orleans or England, people ask me if we have such a thing as an American culture. "To be sure we have," I cry joyously. "Look at the number of authors we have."

Often nowadays it seems to me that everyone in America is at the business of becoming an author. My son of nineteen, who is in another city, has just written me a letter. He tells me that he has written a play. What a warm feeling I have inside myself. "Another author," I say to myself. "Slowly but surely America is coming into its own. Culture is growing here like mushrooms."

I have another son of seventeen. He goes into a room and closes a door. I go trembling along the hallway. uEt tu, Brute," I say to myself. "It is as I hoped. He is at a desk. His brows arc wrinkled. He is composing something."

My dog, when he smells a book or a bottle of ink, wags his tail with joy. How often nowadays I think of the beautiful lines of Julia Moore, Michigan's sweetest singer:

"It is my joy to compose and put words into rhyme

And the success of my first hook is this little notebook of mine"

I remember once going to a dinner given by authors for authors. It was in the city of Chicago. Mr. John Drinkwater, Mr. Sinclair Lewis and myself were the guests of honor.

Voilá—as we say in French—here we were. In the room, besides the three immortals, were some two or three hundred others—all authors.

IT IS so wherever I go. I have recently come II to Europe—to Paris to be exact. I came on a ship. I do not come to Europe often, as I do not often have the price of the passage. However that has nothing to do with the matter. That is not what I intended to tell you. Before I sailed, I met another author on the street. He also was bound for Europe. Will I be betraying a secret if I tell you that authors in general, while they love other authors in the mass, as one loves his native country, do not often love other authors as individuals?

But you sec how it is. They arc often together. It is because of culture. Everyone wants culture and where else is one to get it? You see, I do not mean to suggest that we authors do not have, in our hearts, a deep sympathy and even tenderness for each other. If you arc an author there is something within you that impels you to be talking always in a very cultural way, that is to say, about books, painting and sculpture, and of authorship. You see I am doing it now. I cannot help it.

And while I am on the subject, there is something else I might say. We authors are all very sensitive and the sensitive are cursed with a thing called self-consciousness. "I am a writer. Am I also an artist?" we are always saying to ourselves.

It is a dreadful question and it is always popping up. What we authors do is to reassure each other. Sometimes I am afraid that corruption is creeping in among us. We do love flattery. I tell you this by way of confession. Ordinary people, you sec, will not give us flattery enough, but we authors understand, each of us, the need of the other for flattery. Ordinary people, I suppose, have their own business to which they must attend. They have to go to a store; they have to catch a train. When they see one of us on the street they do not have time to notice the shape of our heads and the delicate lines of our faces. I do not blame ordinary people for this. I am just stating it as a fact.

THE unfortunate part of it is that we authors have too much flattering to do. It is all very nice and comfortable when the other fellow is piling it on for me, but when it comes my turn—what a bore!

However, as I started to say, when I was in New York and about to take a ship, I met another author on the street. He was about to take another ship. Naturally we both expressed great regret that we were not going on the same boat. "My dear fellow, you must get your passage changed. We must by all means be together." "No, you do it. You go on my ship."

A moment of self-sacrifice did come to one of us at the last. I think it was the other fellow. He said something that I am sure he did not mean. Now that I think of it I am quite sure that he was only being literary.

"Oh, Hell, man; I want to be the only author on my ship. You go to the devil."

On the boat I did take, there were six other authors. How many he found on his ship I do not know. I hope he found at least fifty. On my ship no one paid any attention to me. I never had such an uncultural time.

One good thing about constantly meeting other authors is that your mind is kept continually on the alert. If you do not say nice things to your fellow author when you meet him, how are you to expect him to say nice things to you? It is a test of the mind. It keeps you on the alert. You have to be always thinking up new things to say. My dear, my dear, I grow so tired of it sometimes.

Ships loaded with authors. Authors walking everywhere in the street. There is that train you sec over there in the distance. Look; it is just passing between those two hills. Formerly, trains running from town to town in America were loaded with travelling men going from place to place to sell goods. Now the trains are loaded with authors going from place to place to give lectures.

THE travelling men, some of whom I formerly knew, were terribly uncultural, but they were gay dogs. I used to be one myself. In those days when I started on a journey, I went at once into the smoking car and found another of my kind.

We began to tell stories. "Have you heard the one about the mule and the miner?"

"My father used to tell me that one, but here is one that is brand new."

The travelling men with whom I associated during the darker period of my life threw their stories about with reckless abandon, but we authors do not do that. We have to save our stories. My God! Do we not live by them?

Writers, when together, usually speak to each other on the subjects of "form" and "style". It is a much higher type of conversation.

But I was about to say something of the dinner given in Chicago for the three notable writers—that is to say, for Mr. Sinclair Lewis, Mr. John Drinkwater—who is English—and myself.

You will perhaps also notice that in speaking of these three notable writers, I have put myself last. I have done that hoping that if either of these two men have occasion at some time in the future to speak in public of other writers they will put my name in and will put it first. What I wish to convey to you, the reader, is that I am a very subtle man. Everything I do and say has a purpose.

TO return again to the dinner. (It may really have been a fifty-cent luncheon.) There we were—we three notable ones—sitting at a table at the head of the room and naturally, under the circumstances, looking as important as we could. I have to confess that Mr. Drinkwater—being English—succeeded better than Mr. Lewis and myself. Whatever else you may say of present day Englishmen, who are authors, this you must say: "They do succeed in looking more like authors than we Americans can. It is something we must learn."

There we were, I say, and there in the room were the three or four hundred other authors. Having adjusted myself as best I could, that is to say, having made myself sit in a chair and compose my face and head as I thought the face and head of an author should be composed, taking Mr. Drinkwater and not Mr. Lewis as my model, I looked about me.

'There before me in the room sat the five or six hundred other authors. I had at that time lived in Chicago for a long time but had not known how much we had advanced.

In a far corner of the room sat two little old ladies. At first I could hardly believe what my eyes were telling me. They were by way of being aunts of mine—two very respectable and charming little old women.

Well, now I do not propose to take their authorship on my head, and after all they were my aunts by marriage. At first I did not believe they were authors. "How delightful," I thought. "They have in some way managed to get in here in order to pay respect to me."

The thought quite warmed my heart. To be sure, had they wanted to pay me honour they could have met me at any time by simply inviting me to dinner. One of them at least was a very good cook.

They had, however, come into this public place to do me public honour. I thought it very sweet of them and as soon as the luncheon, the necessary speeches and so forth were at an end, I went to them, pressing my way through the throng, that is to say, through the six or seven hundred other authors in the room.

There they were, being very modest, it is true, quite pressed against the wall by the mass of authors, in fact, but each held a book in her hand, and each was the author of the book.

It is all quite true. The impulse toward authorship has in America become something national. It is all very encouraging to one who has at heart the cultural advancement of his native land.

BUT I am presumed to be speaking here of the education of authors. What everyone in America wants to be, I am presumed to be telling them how to be. Ye Gods, Mr. Editor, would it not be better for me to attempt telling these people how to escape being an author.

No. Well, I sec your point. You arc after circulation. If I could really tell people how to do it and do it quickly, your circulation, you think, would go up by leaps and bounds.

Very well, then, I will tell them. If any of your readers really wish to be authors and want to know how to succeed, I will tell them how to do it.

In the first place, and as I am addressing an American audience there is one thing I must tell you which will shock you a little. If you really want to succeed as an author in America, you should be born an Englishman. Very likely you were born poor. It may even be that your own people did not have many opportunities to associate with cultural people. It may even be that you are a clerk in a shoe store.

How are you to know about that great world of which you must necessarily write—if you are to succeed as an author? —That is to say, of the great world of Fashion!

It may seem to you a very hopeless prospect, but I am come to tell you there is hope for you.

There you arc, confined all day in the shoe store, and at night I dare say you are compelled to associate with other shoe clerks and people of that class.

Of course you find them of a very low class. Hardly any of them have any vocabulary to speak of at all. And you must have a simply huge vocabulary if you arc to succeed as a writer. In particular you must have ready at hand to drop here and there in your prose, a lot of very hard words.

Well, my dear man, I have promised to tell you how to succeed as an author in spite of these handicaps, and I will do it. You can read, of course, and that is what you must do. As soon as possible you must cut yourself off, as much as you can, from the life immediately about you and sink yourself into the life of books. It would be a good thing for you if you could read, all you can get hold of, of the books of Mr. . . .

There, I was about to give you the name of a very successful American author who has a beautiful vocabulary, but I will not do it. So few of my fellow authors ever boost me. Why should I do it for them?

And anyway, what I wanted to say was that, being a shoe clerk and being cut off as you arc from real life, you must go to books. Very few clerks are fortunate enough to work in stores where aristocrats or millionaires come to buy their shoes and these are the people you must in the end know most about.

Oh, the conversation of English aristocrats and American millionaires! It is wonderful to hear.

And what lives these people live. We ought to be very grateful to our popular authors who have given us such exact and glowing pictures of these men and women into whose presence we cannot go, and who, in doing so, have be-sprinkled their books with such marvelous words.

Well, there you arc, you sec. I have really told you all I know of authorship. I have told you how to do it. If you arc to succeed as an author in America all you have to do is to read the books of successful authors. It is really very simple. When you hear that a book is a best seller, run and get it. You will rarely be disappointed. Out of every book you will get something that will help you on your way.

I might, to be sure, be very old-fashioned and tell you to write, as simply and clearly as you can, of the life immediately about you. Hut that would be a betrayal. In the first place, who cares for such writing? And in the second place who cares for such lives?

TAKE your own life, for example. Is it not a terrible thing? There, I knew it was. And so is mine.

The lives of these other people, that is to say, of the people of the great world, the lives of millionaires and movie stars, to say nothing of the aristocracy of England, with which our best books are filled, arc of course far beyond our own poor lives. You and I cannot live such lives. It is simply impossible.

We can, however, acquire some little education as we go along. We can increase and enlarge our vocabulary. It may be that if you will do as I suggest—and I think I may promise you success if you do—and do it seriously and for a long time, you will, no doubt, learn many words you cannot pronounce. Hut when you have succeeded and can associate more with other authors you will hear some of them pronounce these words and can sec how it is done. It is like going to a grand dinner where, if you arc at all clever, you will watch and sec how other people use their forks.

And you will also find that other authors who have been before you in the great world, in the world that I might speak of as the field of the cloth of gold, will be glad to tell you any little things you do not know.

They will do almost anything for you, if you will only remember, first of all, when you come into their presence, to speak in glowing terms of their work.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now