Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Playboys of the Campus

How the American Colleges Have Made a Definite Contribution to the Theatre

WALTER PRICHARD EATON

THE winter just passed may be tagged as the one when the colleges handed the ugh to Broadway. Incidentally they handed a happy smile to several managers—in the cash corners of their mouths.

In 1907, when Professor George P. Baker, then of Harvard, inaugurated his pioneer course in playwriting at Cambridge, and the now famous "47 Workshop" came into being, nearly everybody on Broadway, from David Belasco to the elevator boy at Cain's storehouse, indulged in snorts of derision. Before that the only academic influence in our theatre was, they said, the influence of church colleges on musical comedy, best to be observed in Boston after a Harvard-Yale football game. And that condition would remain.

"Playwriting cannot be taught. There is no school of the theatre but the theatre. And the theatre, of course, is Broadway. 'Phis playing with the playhouse in academic circles may be all very well as a pastime, but it is utterly ridiculous as a practical means of guiding and enriching the creative dramatic life of America."

(Broadway didn't put it in just those words, but that was what was meant.)

Well, let us see. Twenty years have now gone bv. Professor Baker has deserted Harvard for Yale, where his department has been endowed with a beautiful theatre. His students have gone out all over America, some to teach similar work in other colleges, some to write plays, some to act in them, some to design scenery, some to direct Little Theatres, some—perhaps the bulk—merely to be more enthusiastic theatre-goers in their communities. In twenty years Harvard has shifted from being the only American college to treat the practical theatre as a branch of education, to being almost the only good college not to. Twenty years is not a long time; it took much longer than that for the professional stage of Broadway to free itself of European dominion and train a crop of native dramatists who could furnish us with even tolerable dramatic fare. Still, in twenty years, this academic study of the drama ought to begin to show some results in the creative life of the nation. Let us take a look at Broadway during the winter of 1926-1927, and see.

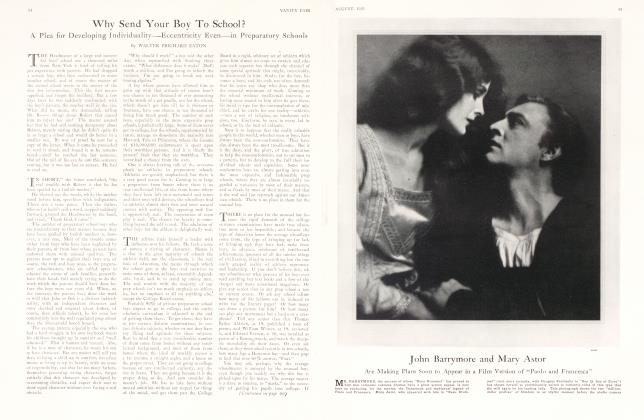

LET us begin with the Theatre Guild, since the Guild has perhaps the most consistent standard of production, and during the past winter certainly achieved the greatest proportion of popular successes. Two of the Guild's Board of Managers, including Lee Simonson, the scenic designer, came under Baker's influence at Harvard. Phillip Moeller, the stage director, was a student of the dramatic courses in Columbia, and Theresa Helburn, the executive director, was similarly influenced at Bryn Mawr. Nothing could be more academic, and less of Broadway, than the influences which shaped the Guild directors in their most plastic years. Two of the four most successful plays the Guild produced last winter were American dramas written by Sidney Howard—The Silver Cord and Ned McCobb's Daughter. And, of course, three years ago Howard won the Pulitzer prize with They Knew What They Wanted. Sidney Howard is a graduate of Professor Baker's playwriting course.

Beyond all doubt, the most popular play of the winter was the racy and authentic melodrama Broadway, the joint work of Phillip Dunning and George Abbott. George Abbott is a graduate of Professor Baker's playwriting course.

Rivalling Broadway in lively colour and almost in popular acclaim is a play called The Barker, written by one Kenyon Nicholson. Nicholson is himself a teacher of playwriting, an assistant to Hatcher Hughes at Columbia. Incidentally, Professor Hughes' play, Hell Bent fer Heaven, won the Pulitzer prize two years ago.

THE two plays which have been most often nominated by the critics for the 1926 Pulitzer Prize (not yet awarded at this writing) are In Abraham's Bosom by Paul Green, and Saturday's Children by Maxwell Anderson (co-author of What Price Glory?). The author of the first play, Mr. Green, is a young instructor of philosophy in the University of North Carolina, and his play is concerned with the problems of negro life in that state. When a student in the University, Green studied playwriting in the course given there by Professor Frederick Koch, and got his inspiration to write drama, and all his knowledge 6f technique, from his experiments with the University Players in their campus theatre. Abraham's Bosom is his first showing on Broadway. But Professor Koch himself is a product of the new movement in the colleges. He was teaching in the University of North Dakota, and putting on student pageants, when he heard of Baker's course at Harvard, went to Cambridge to observe it, and carried back to the Prairie the pioneer playwriting course of the West. The first class to be graduated from this course contained a youth named Maxwell Anderson, who came to New York filled with an ambition to write plays, and trained to seek his material in the life about him, and to render it faithfully. Here, then, arc two of the admittedly best native plays of the past season, best in the sense of sincerity and faithful transcription of life, both stemming directly from academic training, and academic standards of veracity.

But this by no means exhausts the list. Another success of the past winter is the ironic burlesque, Chicago, written by a young woman named Maurine Watkins, formerly a newspaper reporter in the city of hogs and machine gun bandits. Miss Watkins, filled evidently with a great desire to put upon the stage her reaction to the life of that village, being unable to do so in the columns of the Chicago press, sought out Professor Baker at Yale, to learn how to do it. She wrote Chicago in his course there, and it was first produced in the University theatre, not, it is rumored, without considerably shocking the Puritanical elements in New Haven. Be that as it may, Chicago is an academic play; it was planned, developed, and produced, inside the college walls.

Earlier in the season Philip Barry, a graduate of Yale and also of Professor Baker's course when Baker was still at Harvard, produced a fantasy called White Wings. It was not greatly popular, to be sure, but Robert Benchley went six times. It had its admirers, and gave to the season a spice of variety and a touch of the graceful and fantastic. During the season, too, Eugene O'Neill's Beyond the Horizon was revived for a considerable run. O'Neill, generally conceded our leading dramatist, is a graduate of Baker's course. And the man who produced his play, and the talented artist who has been his associate, Kenneth Macgowan and Robert Edmund Jones, arc both products of the academic theatre, and got their first interest and training at Harvard.

Perhaps it is not fair to include in this list Walter Hampden's production of Caponsacchi, a play in blank verse hewn by Arthur Goodrich out of Browning's The Ring and the Book. Though Hampden went to Harvard and Arthur Goodrich is a trustee of Wesleyan, they both attended college before the days of the dramatic awakening. Nevertheless the honourable place they hold in the dramatic world is reflected back as inspiration into the colleges, and, with Winthrop Ames, they may be classed as an important academic influence in our theatre, just on that account.

THIS list is merely for Broadway, and for a single season. It does not include any of the work done outside of New York, in the various Little and Community Theatres through the land, which are often unknown to Broadway, but which locally are of great interest and importance. Some of them are doing excellent things, even judged by exacting professional standards, and nearly all of them are, in their respective communities, the present day equivalent of the old time travelling company;— that is, they and they alone are keeping alive the spoken drama. It is so largely true of these theatres as to be almost the rule, that they are directed not by professionally trained men or women from Broadway, but by academically trained men or women, and that the nucleus of their amateur acting staff and scenic workers is formed of college graduates who have found in the academic courses the impulse for such expression. In other words, the colleges are recreating a theatre beyond Broadway, for the people of America, without any help from Broadway whatsoever.

All this has taken place in two decades, but so quietly that few people even yet seem to grasp the significance of the change, least of all the managers, who no doubt think they are responsible for all the improvements in play writing and production technique. As a matter of fact, they are responsible for practically none of it. It has resulted far more from the improved quality of the men and women coming into the theatre as artists, and this improved quality, in turn, is the direct result of the new collegiate courses in play writing and play production. It is still true that the place to learn to write plays, and to produce plays, is in the theatre. But it is not true, and it never was true, that the theatre is only the professional theatre of commerce. One thousand citizens of Iowa City, gathered in a university hall to see Prof. Mabie's students act Caesar and Cleopatra, constitute a theatre just as much as one thousand semi-morons gathered in the Republic Theatre, on West 42nd St. to witness Abie's Irish Rose. And, in such a university theatre, the student of playwriting not only tries his play on an audience, but brings back to the classroom the fruit of his experience, and with guidance and encouragement sets about correcting his mistakes. Anybody who has ever read plays knows that the vast majority of the manuscripts submitted to managers are hopeless, even those which may contain excellent ideas. They are as hopeless as would be the work of an engineer or chemist who set out to practice those sciences without any training. None of these is produced, and any talent that might lie behind some of them is never developed. But with certain colleges functioning as laboratories of the dramatic arts, a young man or woman with an urge to write or produce or paint scenery can study the rudiments of the art, can find out whether or not the urge is justified by real talent, and can then approach the actual theatre of the people not with an impossible manuscript in his hand, but with one at least sufficiently workmanlike to insure attention.

Continued on page 110

Continued from page 69

Still more important, however, is the fact that in such college courses a group of young people are gathered together animated by a common creative purpose, encouraged by each other's example, and guided and checked by the idealism of the university, not the exigencies of commerce. They not only find artistic stimulation in their mutual association, but they learn to look for their material, and to treat their material, with an eye single to its real dramatic value, and its truth to life. Nobody can deny that by intrinsic genius for stage effect, George M. Cohan is one of the best dramatists we have ever produced. But it is perfectly apparent that Mr. Cohan, beside such a writer as Maxwell Anderson, or Paul Green, has to take a lesser place in our regard, simply from his lack of the ultimate sincerity of the true artist, the ultimate vision for truth. Indeed, between a man like Cohan and a man like Anderson lies the real difference between our drama of twenty years ago and today, between a drama produced almost entirely by a theatre with no background but Broadway, and a drama produced by a theatre in which there is a constantly increasing leaven of college trained, or if you prefer, artistically inspired artists.

In short, through their practical courses in the arts of the theatre, many of our colleges are taking their place today, have indeed taken it, in the creative artistic life of America. This, I think, is a boon to America, and a decided advance in college education. For that reason I am, as a graduate of Harvard, all the more grieved that my own university, where Prof. Baker started the whole movement, has been the one ranking institution to repudiate it, and is now permitting Yale, North Carolina, Iowa, California, and so on, to influence the practical theatre arts of today, while Harvard goes happily back to a philological study of the plays of Beaumont and Fletcher, or awards a Ph. D. for a thesis about the influence of Latin Comedy on the plays of Ben Jonson. I vastly prefer Iowa, where you can get at least an A. M. for a first rate job of stage production. I think it is a good deal more important today to develop a Ben Jonson of our own than to pore endlessly over the works of one dead three hundred years. Certainly Broadway this past winter has borne heartening testimony to the fact that many American Universities think so, even if Harvard doesn't.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now