Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLondon's Passion for American Players

A Footnote to the Discussion of Our Oft Reputed Unpopularity Overseas

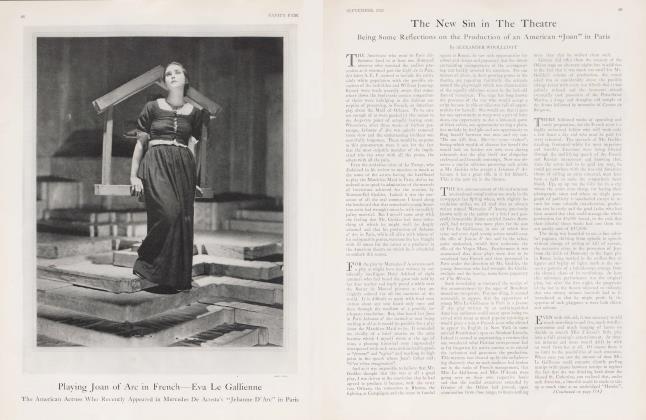

ALEXANDER WOOLLCOTT

EVERY American reaching his native shore in this season of autumnal migration is agreed with his fellows in one respect. As soon as he has embedded Emily's new black pearl in his tooth paste and hidden the flask of Grande Marnier in his camera case, the homing patriot is ready to meet the reporters as they swarm aboard at Quarantine. Approaching them genially and straightway putting the poor wretches at their ease by assuring them with a jovial smile that he used to be a newspaperman once upon a time himself, he is ready to make his statement, which, with sundry minor variations, runs somewhat as follows: "Americans are unpopular abroad."

This utterance has been made so often of late that the stay-at-homes feel obliged, as a matter of common courtesy, to give each returning traveler a chance to repeat it. I find a tendency to cross-question me on the subject manifested by friends who could not by any chance be conceivably interested in the answer. Usually I find myself in a quagmire of misgivings on the topic, being cursed with a suspicion that most Americans arc also unpopular at home and that, any way, since the first frontier was crossed by the Neanderthal man, gadabouts have always been unpopular abroad. But such refinements on the subject would have been gratuitous this fall.

"And how," they ask automatically, "do the Americans get on with the French?"

TO which deponent sayeth nothing, not knowing. For in three weeks spent in France, I did not happen to run across any French people. Like every one else, I have read of busfuls of American tourists being stoned by Parisians and had 1 stumbled on any natives in my wanderings it seems reasonable to suppose that they would not have resisted the temptation to shy a few boulders at any target so wide and inviting. Fortunately I encountered only other expatriates and he who is without passports must cast the first stone. Ask me, if you wish, how the Americans get on with the Argentines, the Italians, the Russians and even (if you want to stir up a hornet's nest) how they get on with the other Americans. But, with a single unilluminating exception, I had discourse with only one native in all the route from Calais to Monte Carlo. That was the Baron Henri Louis Legrange, with whom I chatted daily at Antibes as he bared his satin skin to the morning sun on opalescent rocks beside a turquoise sea. But one does not feel free to introduce the vexed questions of international finance into the peace of a baronial sun-bath and besides I felt such discussion would be misplaced considering the baron's years which arc, at this writing, two.

Then I hear, too, that Americans are quite unpopular in London, and, considering the manner and appearance of some that I saw there this summer, it does seem plausible. But if, as I have been gravely assured, the entire island seethes with dislike for this country and all its inhabitants (including Mr. Coolidge and your correspondent) I find it difficult to account for the way in which all the American players who appear on the London stage are clasped to the withered bosom of the London playgoer. It isn't merely that the man in the pit, embittered by the Yankee debt settlement, would refrain (after an inward struggle) from hurling vegetable marrows at the upstart invaders. The players from this country are received not merely with cordiality but with far warmer acclaim than ever any of them experienced in their native land.

When the lovely and immensely capable Jane Cowl made her first appearance on the London stage in June, the ensuing hulla-baloo from pit and stall could be heard as far as Land's End. And after the final curtain fell, only the fact that, with all the good will in the world, a mob can scarcely take the horses from an already horseless carriage, prevented her equipage from being dragged in triumph from the Duke of York's Theatre to her little house in the shadow of St. James's Palace.

ONCE in the first fortnight of the engagement, I passed by the stage alley of that playhouse where Charles Frohman used to rule. It was a good hour and a half after the end of the play and a fine drizzle—as fine a drizzle as one could ask—was emptying the sidewalks. But, at the stage door of the Duke of York's, a faithful band of playgoers was still standing guard, waiting for a glimpse of Miss Cowl on her way home from work.

And this, mind you, was for her work in Noel Coward's foolish play Easy Virtue, which he might have had the grace to call The Hundredth Mrs. Tanqueray. That is the drama in which Miss Cowl disported herself uneventfully at the Empire in New York last spring, the one in which, at the peak and climax of the second act, she nightly smashed to bits a small, inexpensive reproduction of the Venus de Milo, thus adding, however, in a long engagement, a considerable item to the really staggering crockery bill of last season's emotional dramas. The central role—that of a woman with a past who tries, unsuccessfully, to become a county lady— is one so easy for Miss Cowl that she must find it about as much of a strain as Elsie Janis experienced in turning a cartwheel. They say Miss Cowl will linger to play Juliet for the Londoners who so honoured the Flamlet we recently shipped over to them. If her performance in Easy Virtue caused a stir along the Strand, her Juliet, I imagine, should knock down the Tower of London.

Of course, such demonstrations are by no means reserved for Americans. For reasons which might deserve a footnote in any modern work on psychology (in the chapter on repressions and escapes) the Londoner is a far more passionate playgoer than his cousin in New York. His lady is even worse. She thinks nothing at all of sitting all day (with a bit of sewing to do and some sandwiches) waiting for the doer of the pit to open for the night's performance and then she's good for another two hours guarding the stage entrance, with her umbrella in one hand and her autograph album in the other.

The outcries of approval and satisfaction on first nights are so stentorian as faintly to alarm the stranger. When that flagrantly American opus Is Zat So? had its London 'premiere early last spring, James Gleason and Robert Armstrong, who deserted the New York cast for the London engagement, were fairly stunned by the uproar coming out of the dark on the other side of the footlights. And when these ructions continued after the fall of the first-act curtain, it needed all the bullying of the English cast to persuade them that the demonstration was friendly and that they ought to step out and take a bow. They thought they were being handed what, in their own quaint patois, is known as the raspberry. Is Zat So? entered at once into the affections of the English playgoer, despite the fact that he had to be assisted through its darker dialogue by a program glossary which carefully explained to him the meaning of such phrases as "apple sauce" and "banana oil", which set him straight on the difference between a "set up", a "wise-crack" and some "soft jack" and which kept him from confusion at those moments when a girl might be referred to as cither a dame, a skirt, a wren, a jane, a frail or, haply, a. broad.

THEN the Astaires continue their reign which seems destined to last as long as that of the fifth George. These youngsters were born to tread the measures of Master Gershwin and, in the mazes of his dances, they seem quite unhampered by such inconveniences as the ordinary human skeleton can provide.

And of course there is always Talullah Bankhead, a minor American actress who wandered into London a few seasons ago and has played practically all the leading roles available there since. After a session as Iris March in The Green Hat, she has been sharing with Glenn Anders the honours of They Knezv What They Wanted.

Finally, one balmy July night at the London Pavillion—that is the music hall ruled at present by the resilient Mr. Cochran—after the sprightly Spindly had done her turn, the dropcurtain fell, the footlights shone out and onto the little bit of forestage wandered an amiable and uncouth stranger, hands in pockets and chewing gum in jaw. He grinned sheepishly and started to ruminate aloud.

"Well," he said, "I'm supposed to come out here and talk a while. The manager tells me they's a lot of mighty fine people here tonight, but that don't mean much to me. This ain't my first experience playin' before titled folk. Of course, the first time it ever happened to me, I was pretty excited. That was back in New York the night the manager came back stage and told me Sir Harry Lauder was in the audience."

The audience stirred and chuckled.

"I was pretty set up about it," the drawl continued, "but since I come over here, I've learned that a Sir ain't so much to brag about. They tell me the Sir is the Ford of titles. I understand they's to be a bill put through the House of Commons making it a law that you've got to treat knights just like you'd treat anybody else."

(Continued on page 110)

Continued from page 65

At which a number of dukes guffawed and beat the nearest knights jovially on the back. In no time that audience was warming to our Will Rogers. And yet, I felt a vague discomfort, a sense of a resistance to him. For Rogers was ill at ease. He was working without his chaps and rope, but it wasn't that. He was working without his confidence. He was awed by his audience and they knew it and liked him the less on that account—less than they would have liked him had he rattled on with all the contempt which every audience so richly deserves. But they liked him a lot, they even let him talk on the Avar and the debt without hurling him into the street. They are so immensely cordial to all our players Avho come before them that I want to be there and watch the roof come off if ever the night comes when a London curtain rises on the master of them all—Al Jolson.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now