Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe New Sin in The Theatre

Being Some Reflections on the Production of an American "Joan" in Paris

ALEXANDER WOOLLCOTT

THE Americans who went to Paris this Summer (and to at least one dismayed -UL observer who watched the endless procession as it swarmed past the Cafe de la Patx, this latest A. K. F. seemed to include the entire adult white population with the possible exception of the bedridden and William Jennings Brvan) were made uneasily aware that somewhere down the boulevards certain compatriots of theirs were indulging in the dubious enterprise of presenting, in French, an American play about the Maid of Orleans. To be sure not enough of us were goaded by this rumor to the desperate point of actually buying scats. Wherefore, after three weeks of forlorn patronage, Jehanne dJ Arc was quietly removed from view and the embarrassing incident was mercifully forgotten. There would be no point to this post-mortem were it not for the fact that the most culpable member of the implicated trio ran away with all the praise, the others with all the pain.

Even the acidulous critic of Le Temps, who disdained in his review to mention so much as the name of the actress having the hardihood to play the Matchless Maid in Paris, did so far unbend as to speak in admiration of the marvels of investiture achieved for the occasion by Norman-Bel Geddes. Indeed it was the consensus of all the oral comment I heard along the boulevard that that remarkable young American artist had wrought miracles with incredibly paltry material. But I myself came away with the feeling that Mr. Geddes had done something of which he might well be deeply ashamed and that his production of Jehanne d' Arc in Paris, while all alive with tokens of his indisputable genius, was none the less fraught with ill omen for the career as a producer in the American theatre on which he is scheduled to embark this season.

FOR the play by Mercedes d' Acosta was such a play as might have been written by any tolerably intelligent Daisy Ashford of eight summers who had heard the great tale told by her dear teacher and haply pored a while over the Boutet de Monvcl pictures as they are brightly colored for all the nurseries of the world. It is difficult to speak with final conviction about any text heard only once and then through the medium of a possibly inadequate translation. But, thus heard last June in Paris Jehanne an Arc seemed as near being nothing at all as it would be possible for a play about the Matchless Maid to be. It reminded me vividly of a brief treatise on the same heroine which I myself wrote at the age of nine, a pleasing historical essay impressively interspersed with such rare, untranslatable patois as "femme" and "eglise" and reaching its high point in the speech where Joan's father said: "C'est vôtre imagination".

And as it was impossible to believe that Mr. Geddes thought that this was at all a good play, I was driven to the conviction that he had agreed to produce it because, with the entry into Orleans, the coronation at Rheims, the fighting at Ccmpiegnc and the scene in fateful square at Rouen, he saw such opportunities for colour and design and pageantry that the almost excruciating unimportance of the accompanying text: hardly arrested his attention. For our masters of decor, in their growing power in the theatre, are repeating faithfully the attitude toward the playwright which was characteristic of the equally oblivious actress in the bad old days of yesteryear. The stage has long known the processes of the star who would accept a script because its role or roles was full of opportunities for herself. She would see that it gave her one opportunity to weep over a pair of baby shoes, one opportunity to don a low-neck gown of black velvet, one opportunity to sing a plaintive melody by firelight and one opportunity to fling herself between two men and cry out: "Do not kill him. lie—is—your—father". Seeing which wealth of chances for herself she would look no further nor note even during rehearsals that the play itself was altogether cock-eyed and beneath contempt. Now one observes a similar oblivion possessing such artists as Mr. Geddes who accepts a Jehanne J' Arc because it has a great role in it for himself. This is the new sin in the theatre.

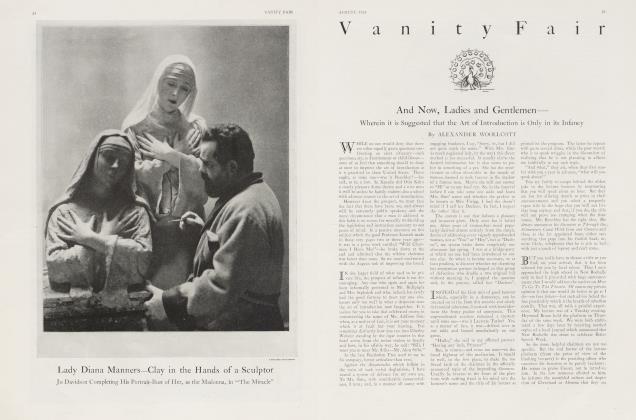

THE first announcement of this unfortunate international complication was made in the newspapers last Spring when, with slightly incredulous smiles, wc all read that an obscure writer named Mercedes d' Acosta, previously known only as the author of a brief and generally lamentable drama entitled Sandro Botticelli, had written two more plays for the uses of Eva Le Gallicnnc, in one of which that tense and even rigid young actress would essay the role of Jeanne d' Arc and in the other, quite unabashed, would then undertake the role of the Virgin Mary. Furthermore it was announced that these plays were first to be translated into French and then presented in Paris under the direction of Mr. Geddes, the young American who had wrought the Gothic twilight and the hearty, tumultuous pageantry of The Miracle.

Such incredulity as tinctured the receipt of this announcement by the sages of Broadway turned on two points. For one thing, it seemed reasonable to suppose that the appearance of young Miss Le Gallicnnc in Paris in a Jeanne d' Arc play written by an undistinguished American authoress could count upon being received with about as much popular rejoicing as would greet a minor French actor who elected to appear in English in New York in some untried Frenchman's opus on Abraham Lincoln. Indeed it seemed so unpromising a venture that one wondered what Parisian entrepreneur had so far forgotten his native caution as to extend the invitation and guarantee the production. This mvstcrv was cleared up by the enlightening discoverv that no such madness had broken out in the ranks of French management, that Miss Le Gallicnnc and Miss D'Acosta were going over on their own respective hooks and that the cordial assurances extended by Gemicr of the Odeon had proved, upon examination from close range, to mean nothing more than that he wished them well.

Gémier did offer them the tenancy of the Odeon stage on alternate nights but in addition to the fact that it was much too small for Mr. Geddes's scheme of production, the rental asked was so considerably above tile possible takings (even with every seat filled) that it was politely refused and the innocents abroad eventually took possession of the Porte-Saint Martin, a dingy and draught}old temple of the drama hallowed by memories of Cyrano de Bergerac.

THERE followed weeks of agonizing and costly preparation, for the French actor is a highly unionized fellow who will work only a lew hours a dav and who must be paid tor every rehearsal. The Spectacle of Mr. Geddes standing frustrated while his most imperious and irascible directions were being filtered through the mollifying speech of the French and Russian interpreters and knowing that, since the actors had to be paid any way, he could get nowhere with the fine old American threat of calling an extra rehearsal, must have been a sight to make the sympathetic heart bleed. Up, up up ran the bills for in a city where the actors even charge for having their photographs taken and where no single paragraph of publicity is vouchsafed except in return for some valuable consideration, production can be costly and the good ladies who had been assured that they could manage the whole production for $5,000 found, in the end, that their blissful three weeks had cost them the not untidy sum of $37,000.

The thing was beautiful to see, a fine colorful pageant, shifting from episode to episode without change of setting or fall of curtain, the successive crises in the procession ol loan from tlie fields of Domrcmy to the fagot pile in Rouen being marked in the endless flux ol figures and byplay of lights much as the successive patterns of a kaleidoscope emerge from the chronic chaos of its revolutions. At least this unbroken performance was the original plan, but after the first night, the proprietor of the bar in the theatre objected so violently that two twenty minute intervals had to be introduced so that he might profit by the appetite of such playgoers as were both thirsty and solvent.

EVEN with this aid, it was necessary to add much marching to and fro, much wordles pantomime and much banging of lances on shields to stretch Miss d'Acosta's little play into a full evening's entertainment. At timeten minutes and more would drift by with no word from her at all. Of course there is no limit to the possibilities of such extension. When once you saw the amount oi time Mis Le Gallienne could consume silently peeling turnips with pauses between turnips to register the fact that she was thinking hard about the blessed St. Catherine, you realized that, under such direction, a limerick could be made to take up as much time as an unabridged "Hamlet".

(Continued on page 114)

(Continued from page 69)

And as this went on and on, it dawned upon you that far from being distressed by the absence of a lovely and enkindling text, Mr. Geddes was actually happy in the fact that there was really no play there at all, no pesky dramatist littering up the stage with her scenario and tripping up his lovely processions with the nuisance of her words. Plenty of folk there were to crowd around Mr. Geddes after each performance, patting him on the back and telling him how marvellous it was that he had achieved such thrilling splendor with such meagre cues from the playwright. These enthusiasts bowed low before him and fought with one another for the honor of buying his drinks on the terrasse of the Cafe Nafolitain after the play. I suppose if he had come to Paris and achieved the same effects by producing the multiplication table, they would have just had to kiss him.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now