Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

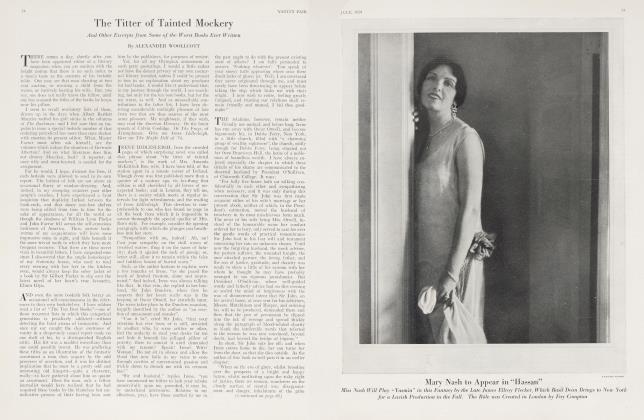

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Coming of Raquel Meller

The Amazing Career of a Spanish Chanteuse Who Began as a Blind Street Singer

ALEXANDER WOOLLCOTT

WITH her two hundred and fi ftv birds left lonesome behind in her villa at St. Cloud but (by special dispensation of a wry-faced French Line) with five of her six dogs occupying the adjoining cabin, the incomparable Meller will set sail for these shores the first week in April. She is, I suppose, the first lady of the European music halls and since an American management has now so far flung caution to the winds as to agree to pay her $6,000 a week for the visit, the least we all can do is to buy seats for her concerts and, in the meantime, meet and come to some agreement as to how we are going to pronounce her name.

On this point, the arguments in Paris have been singularly bitter. They do say that of the calls to which the Paris ambulances responded during the first six months of the year just past, a little more than half were occasioned by the knife-wounds, facial lesions, scalp abrasions and traces of mayhem arising between disputants as to how Meller should be pronounced. She is of Catalan stock, but, since there are many dialects in her cuello de bosque, I cannot pretend to know the right of the matter. I merely submit the fact that she herself pronounces it as if it were spelled Mavairc.

RAQUEL MELLER was born of strolling players in Barcelona and grew up underfoot in a troupe of Spanish pan tom i mists. For a time in her childhood, her sight failed her and for two years it was a blind girl who sang in the hill towns and Tuscany to which her folks had drifted—sang on the street corners at night as Trilby sang with Svengali and Gecko at her side long ago. She will tell you that a miracle gave back her eyes. It was an old beldame in Siena who brewed a mysterious ointment for their hurt but who, to make assurance doubly sure, bade her pray also to the good Saint Catherine of that sun-scorched and lovely city. The prayers were answered.

Meller had found some acceptance in her own city, but the conquest of Paris did not come until the year after the Germans had abandoned their most recent effort to capture it. When finally she stormed the begrudging city, it was by the terms of an agreement she herself proposed. She was to sing to Paris without pay for two weeks and then talk shop. At the end of that fortnight, the city was hers. And England was beckoning. You can measure that Parisian success by the fact that when she crossed the channel, a London music hall was delighted, or at least willing, to pay 300 pounds a week for the turn she could do in its program.

At that time, Raquel Meller had a husband. He was an Argentinian journalist she had acquired in the days of her comparative obscuritv, and the tale of that marriage repeats the history of so many such alliances. The good .Argentinian, it seems, did not at all relish the prospect of a wife turning famous on him. Wherefore the Paris triumph left him a trifle testy.

But it would take one dowered with the pantomimic gift of Meller herself to paint the domestic scene the morning after the London debut. As she tells the story, she awoke all eagerness to hear the London verdict, but, since she was unable to read or understand a word of English, she was dependent on the reportorial faculty of her lord and master. He gave her a ten-shilling note to go out to the corner and buy the papers and then, when he had finished his coffee, he was so good as to read aloud excerpts from the criticisms. 'File young chanteuse, sitting there beside his bed which was buried under a very counterpane of newsprint, heard through the sluggish medium of faltering translation that she had failed to please London, that her voice was no great shakes and that her style would leave the strange city cold. Meller, it seems, was something terrible.

IT WAS not until three nights before the engagement was to end that the dejected ladv stumbled on some compatriots who had also read the papers and who assured her that the critics were by way of being quite delirious about her.

However, the menage did not come to an end until Meller fled the home he made for her the next spring in his own Buenos Ayres. Even then he gave chase and had her arrested. Flic charge seemed to be that no woman would leave him unless she were mad, that she rather definitely had left him and was, ergo, mad as a hatter. In that South American court there ensued a scene of the kind Meller can play best. The famous eyes glowed like coals. Her gestures were superb. The court-room was hushed as she rose slowly to her full height and said:

"My lord, it is true. I have been mad. And that man was my only madness." The judge was so profoundly affected that he took her home with him.

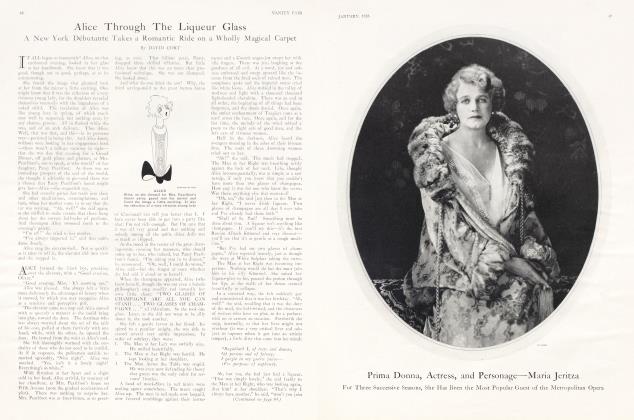

In Paris Meller holds tile stage for a little more than an hour, as one number embedded in a shoddy makeshift revue so poor in entertainment that one becomes expert in timing a breathless arrival at the theatre just as the orchestra is breaking into the prelude of the great lady's first song. She is a grave, singularly tranquil woman in her early thirties, a woman whose sloe-black hair, blue eves and cleft chin somehow bring back the profile of Julia Marlowe as it was tucked into a mvriad adoring bureau-mirrors in this country five and twenty years ago.

MELLER dips into the folk-songs of her 1 v 11 own countryside and the rest of Spain, each songcostumed to the hilt (while the patient Paris audience waits), each song sung with a lot of good acting thrown in. A young Spanish Yvette Guilbert, you might call her, and still leave a good deal unsaid, a good deal for instance, about the sly, shy art and all-conquering charm of the Yioletera song of which the tune and the imitation has long been familiar in America. That is the little street-singer's refrain, in the course of which Meller goes down into the audience with her flower-basket on her arm and veiled mischief in her meditative eve. As she distributes her bouquets with infinite graciousness, it is a sight to see the men tlo battle for them and more especially to see how the great, fat, fly-blown tourists from this countrv, when, blushing at her favor, they step forward in the aisle to take the flowers from her hand, become suddenly as small boys going up to teacher's desk to get their prize.

It has been thought impractical to try to absorb so leisurely, so individual and so costly an artist into the hurly-burly of an American revue. Wherefore her American manager plans just to let Meller go it alone, as she does in her own Madrid. Her present contract is with E. Ray Goetz, the husband of Irene Bordoni.

It is not the first contract for this country which she has signed and when she failed last time to make the promised appearance, there were a thousand rumours as to why. These ranged all the way from the tale that she was mortally ill to the tale that she was so fond of the King of Spain she just could not bear to sail so far away from him—the poor King of Spain who must share with the Prince of Wales these clays the burden of all such legends now that the available kings are so few, so venerable and —like the present beauteous majesty of Denmark, let us say,—so unassociable with the notions of romance. In thus groping for an explanation of Meller's astounding reluctance to invade America, it occurred to few Americans that perhaps she did not want to come and to still fewer that there really was no reason why she should.

Continued on page 92

Continued from page 37

Yet, if you will picture the emotions of Laurette Taylor or Al Jolson or Ethel Barrymore on being summoned to quit their New York and play an extended engagement in Peru, you will grasp the state of mind of the Parisian favorite at whose door an American manager comes knocking, contract in hand. Such a favorite has nothing to gain from such a tour except money, for whatever increment of prestige the tour might also yield would be taken from them at the incorruptible Douane of French indifference to what the outside world thinks. Wherefore, no star of the French theatre has ever swung this far out of its proper orbit except through pique or bankruptcy or a sudden shrewd suspicion that it were well to give Paris a rest.

Sixty years ago, the first of them thus faced an audience from the stage of the Academy of Music in New York—then a monstrous building way out in the suburbs, now a chill temple left behind by the moving city and scheduled for dismemberment. Her name was Rachel and she had come to New York only because she was cross at Paris for taking Ristori to its heart. As she flung the Tecla pearls of Racine before the New York swine, back home in Paris she was thought of as playing to an audience of redskins and blackamoors and, deep in their hearts, the Parisians will think of their Meller this Spring as doing the same.

Yet, when she has completed the motion picture of Carmen at which she has been working for some weeks in her own Pyrenees and for which she is to be paid the far from untidy sum of 2,000,000 francs, she will, I think, set sail. She is not incapable of suspecting that Paris will enjoy her more after a brief vacation and, after all, $6,000 a week is $6,000. And $6,000 is what the doughboys used to call beaucoup jack.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now