Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

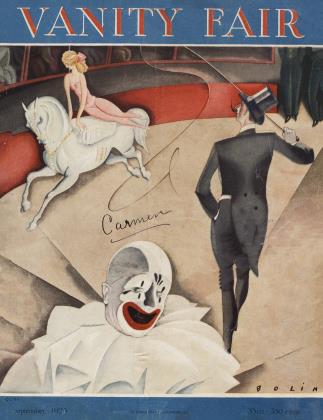

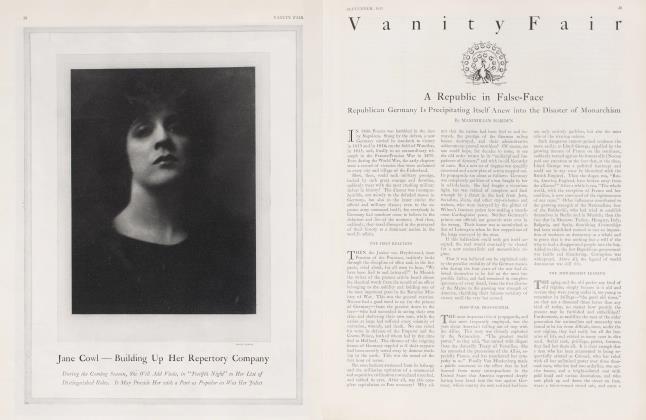

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowJean Cocteau as a Graphic Artist

E. E. CUMMINGS

The French Critic, Novelist and Poet "Unties Writing" with Surprising Originality

WHATEVER the words "Jean Cocteau" may convey to readers of Vanity Fair, to which he has contributed occasional of his masterpieces, it is highly probable that "modern French writer," or "poet, satirist and dramatist," is all that most Americans associate with this well known name.

I must confess that to me "Jean Cocteau" meant (until very recently) even less: to wit, "gilt-edged literary flaneur." I must also confess that my only definitely agreeable contact with Cocteau's work had been established with his ballet Les Maries de la Tour Eiffel; which articulate spectacle, alone and of itself, seemed to justify the existence of the otherwise deafand-dumb Swedish Ballet. As a final confession, I must state, that having been more amused by Les Maries than by anything else in Paris—more, even, than by the police—I entertained a wish to meet the author of this excellent satire, but that my wish died an unnatural death. For at the apartment of Louis Galantiere (who has brilliantly translated several of Cocteau's works) a militant suferrealist writer and one of the most charming of people, by name Arragon, described his distinguished contemporary, Jean Cocteau, in terms so vivid as to convince me that, coming after such a portrait, Cocteau himself would be a distinct anticlimax.

On this occasion Arragon (in his best form) made several enormous assertions; the smallest of which was, that the renowned poet and author of such novels as Thomas Flmfosteur, Le Grand Ecart, etc., etc., did not know how to write French. My surprise when Arragon uttered this very superrealist statement was by no means negligible; but I was infinitely more surprised to learn that Jean Cocteau— doubtless overhearing, from the Eiffel Tower radio station, or in some even more obscure manner, those terrible words—had been moved to produce a volume, not of poems, nor yet of prose, but of drawings. My third surprise came when I opened this book and read the first words of the dedication to Picasso: "Poets don't draw."

Cocteau continues: "They (poets) untie writing and then tie it up again differently. Which is why I allow myself to dedicate to you a few strokes made on blotters, tablecloths and backs of envelopes. Without your advice I'd never have dared put them together."

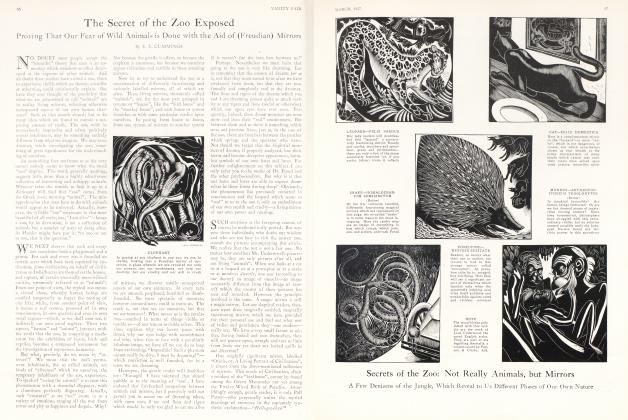

Judging by this profound and brittle bow to the greatest living draughtsman, and knowing Cocteau's predilection for satire, I anticipated a mass of imitative pretense. And once again I was surprised. For Desseins (as this collection of more than 200 of Cocteau's drawings is modestly entitled) reveals itself as a rather lengthy and random concoction of portrait sketches, scenes, caricatures, scrawls, imaginings—or what you will—strictly by a "poetic ironist" of this day and time, and possessing so much originality that if M. Picasso be to blame for its publication the world owes him a new debt of gratitude.

But let us take a few examples of Cocteau's drawing (the book is on sale in most of the New York book stores)—why not the person with the pipe, called Picasso, for instance?

NOBODY, I am sure, will deny one thing: meeting him for the first time, the flcsh-and-blood Picasso is a troll who has just sprung out of the ground. He is not a man. Picasso himself, I reiterate, is a troll—tightly made, genial, clinched, eyeful!, and moreover (as E. O. once remarked, descending the Elysees with me one fragile and immortal evening) "with little velvet feet such as dolls should have." Returning, now, to what I shall call this portrait of Picasso by Cocteau—let me assure any interested person who has not found him—or herself face to face with the original, that what Cocteau's drawing expresses, first of all, is an uncouth aliveness which Picasso's actual presence emanates. In other words, this sketch apprehends— in a spontaneous, acutely personal way—the tactile stimulus which a glimpse of the Spaniard, creature, or genius, called "Picasso" involves: the feathery jolt or, so to speak, shock, of confrontation.

(Continued on page 94)

(Continued from page 46)

Now let us consider a bit the drawing by Cocteau which is called P. Picasso-Igor Stravinsky. In this drawing, Jean Cocteau (the poet, the satirist, the Parisian, the literarv idol) stands oft—politely, maliciously portraying two celebrities of the "esthetic renaissance" of modern Paris, both of them foreigners, who happen also to be the world's greatest living painter and the world's greatest living composer. The extremely trenchant characterization admits of no tricks—the observer's vision is direct —here again, we are refreshed by that rarest of all virtues: spontaneity.

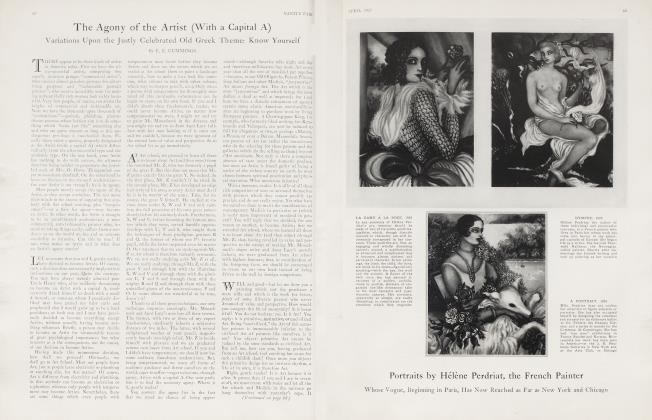

The President of the French Republic, in itself a compelling delineation (which I reproduce) of M. Millerand, of contemporary politics, and of politicians in general should be compared with another drawing of the same personage, (not reproduced here) entitled "M. Millerand leaves Toulon" (in a wonderful gollywog automobile, with too much flunkeyism and too many salutes) ; just as the Picasso-Stravinsky drawing should be compared with "Stravinsky playing the Sucre de Printemps" (a portrait not only of Stravinsky in action, but of his music as well—for from the piano issue wire-ghost-materializations, angular weirdnesses, remarkably suggestive of this composer's unique combinations of timbres.) And now, if one contrasts Cocteau's version of the president of the French Republic with "caricatures" having for their parody our own Coolidge, one begins to realize how insensitive most of the pictorial satire is which is being perpetrated in the U. S. A.—not that one can't mention Bob Minor, Covarrubias (via Mexico), Cropper, Frueh—and also, if one is peculiarly wide-awake, one begins to suspect that whereas Art is mobile, all mere classifications are stationary. (Take, for instance, the following specimen of classification, which adorns an article on caricature in the Encyclopaedia Britannica: "Few traces of the comic are discoverable in Egyptian art— such papyri of a satirical tendency as are known to exist, appearing to belong rather to the class of ithyp hallic drolleries [s/c] than to that of the ironical grotesque"

If this means anything it should be shot at sunrise.)

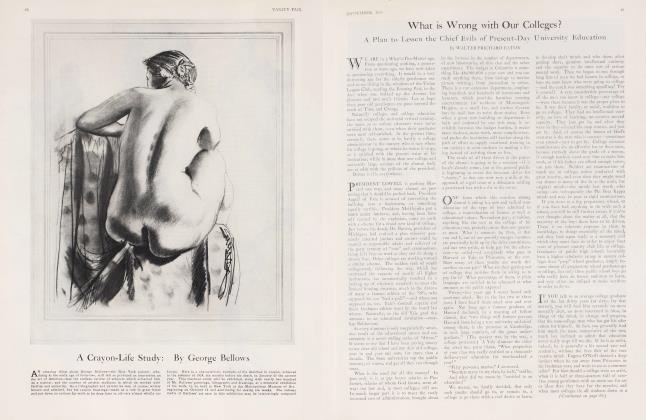

TO PROCEED further with Cocteau's drawings: I wonder just how any classification could effect Cocteau's extraordinary mobile interpretation of Georges Auric, the bright particular star in that singularly unluminous constellation of composers known as Les Six? Less intuitive, coarser, than the ectoplasmic Auric, but still a notable achievement, is another of Cocteau's satires called L'Expressioniste—a roly-poly personage, lolling over backward and dangerously warping the unhappy piano in a hey-day of unordered ecstasy.

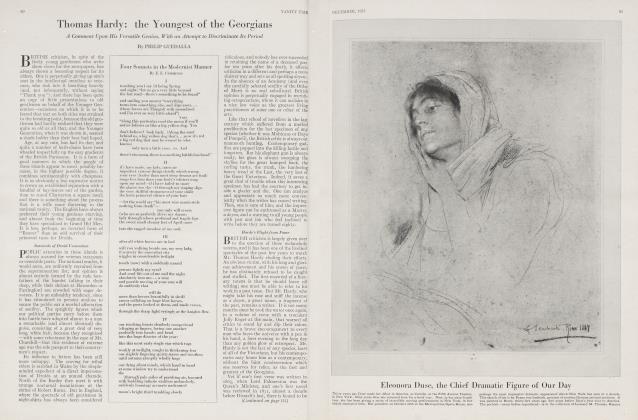

Next we come to the portrait of Pierre Loti. Primarily, this drawing is the creation of an extremely sensitive individual: secondarily, it is the reaction of a "modern" (though bv no means "super-realistic") writer to the "great literary figure of established reputation," the (defunct) "national genius," the over-worshipped narrator of exotic and irridescent tales. Anybody even superficially acquainted with the work (play would be a better word) of Loti, or with his literary-naval career, or with both, cannot fail to be impressed by the cruel delicacy, the unpitying skill, with which he has here been snared.

And now (at a dreadful risk) I should like to make a very few general remarks. The drawings from Cocteau's book selected here for reproduction give a fairly accurate idea of what Cocteau means, when he says that a poet "unties writing and ties it up again differently," in so far as such a statement means anything whatever (or in so far as writing resembles a necktie.) The point, however, is this: a writer, assisted by "blotters, tablecloths and backs of envelopes," has presented us with a collection of what he prefers to call "strokes," certain of which are—to employ the most abused word in our language—beautiful. A number of these "strokes" (like the Picasso-Stravinsky sketch) may, if properly cued, roll into the pocket of "caricaturewhereas others, like a superb line drawing of two sumptuous horses, which Cocteau fortunately calls Les Rimes Riches, refuse to occupy any pigeonhole, except the meaningless one of "Art." Moreover, in the course of perusing this book of Desseins, we encounter a variety of drawings which insist on falling into several categories at once; which is why I stressed, a moment ago, the dangerous futility of classification. Finally, there is a thing (no better term suggests itself) called Le Chant du Condamne a Mort, whose few lines are responsible for the most gruesomely morbid emanation which I have yet encountered in a drawing (although, perhaps, a person has to have known prisons to appreciate the precise flavor)—and this "Song" silences, to my thinking, any kind of classification, unless we are content with the label: Cocteauism.

This mention of "morbid" brings me to the drawings comprised in Cocteau's latest book, the most remarkable group, unquestionably, is Le Mauvais Lieu. The "content" or "subject matter" of the drawings in this group (or rather, the conventional prejudice aroused by that content) will render their appreciation, in the land of the free, problematic. Nevertheless, be they "ithyphallic drolleries" or be they something else ("works of art," for example), certain of these Mauvais Lieu satires—along with a few other ironic "morbidities" and a goodly number of drawings whose subject matter will not generate a qualm in the soul of the most vicious of moralists—establish beyond question the fact that Jean Cocteau, whom we have hitherto known as a writer, is a draughtsman of first-rate sensitiveness.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now