Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Agony of the Artist (With a Capital A)

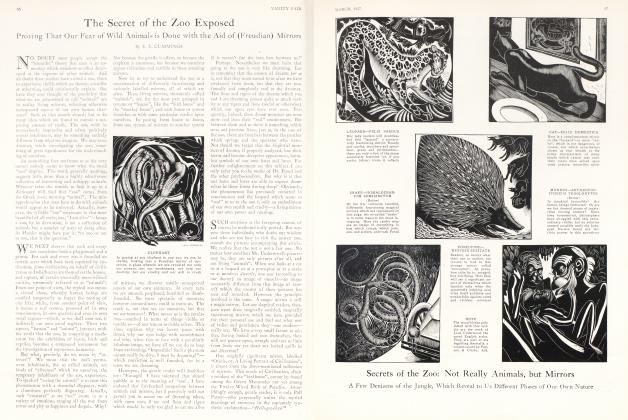

Variations Upon the Justly Celebrated Old Greek Theme: Know Yourself

E. E. CUMMINGS

THERE appear to be three kinds of artists in America today. First we have the ultra-successful artists, comprising two equally insincere groups: "commercial artists", who concoct almost priceless pictures for advertising purposes and "fashionable portrait painters", who receive incredible sums for making unbeautifully rich women look richly beautiful. Very few people, of course, can attain the heights of commercial and fashionable art. Next we have the thousands upon thousands of "academicians"—patient, plodding, platitudinous persons, whose loftiest aim is to do something which "looks just like" something else and who are quite content so long as this undangerous privilege is vouchsafed them. Finally there exists a species, properly designated as the Artist (with a capital A) which differs radically from the ultra-successful type and the academic type. On the one hand, your Artist has nothing to do with success, his ultimate function being neither to perpetuate the jewelled neck of Mrs. O. Howe Thingumbob nor yet to assassinate dandruff. On the other hand he bears no likeness to the tranquil academician— for your Artist is not tranquil; he is in agony.

Most people merely accept this agony of the Artist, as they accept evolution. The rest move their minds to the extent of supposing that anybody with Art school training, plus "temperament"—or a flair for agony—may become an Artist. In other words, the Artist is thought to be an unsublimated academician; a non-commercial, anti-fashionable painter who, instead of taking things easily, suffers from a tendency to set the world on fire and an extreme sensibility to injustice. Can this be true? If not, what makes an Artist and in what does an Artist's agony consist?

Let us assume that you and I, gentle reader, have decided to become Artists. Of course, such a decision does not necessarily imply artistic inclinations on our part. Quite the contrary. You may have always secretly admired poor Uncle Henry who, after suddenly threatening to become an Artist with a capital A, inadvertently drank himself to death with a small d instead; or someone whom I peculiarly disliked may have patted my baby curls and prophesied that I would grow up to be a bank president; or both you and I may have previously decided to become everything except Artists, without actually having become anything whatever. Briefly, a person may decide to become an Artist for innumerable reasons of great psychological importance; but what interests us is the consequences, not the causes, of our decision to become Artists.

Having made this momentous decision, how shall we proceed? Obviously, we shall go to Art School. Must not people learn Art, just as people learn electricity or plumbing or anything else, for that matter? Of course, Art is different from electricity and plumbing, in that anybody can become an electrician or a plumber, whereas only people with temperament may become Artists. Nevertheless, there arc some things which even people with temperament must know before they become Artists and these are the secrets which are revealed at Art school (how to paint a landscape correct!v, how to make a face look like someone, what colours to mix with other colours, which way to sharpen pencils, etc.). Only when a person with temperament has thoroughly mastered all this invaluable information can he begin to create on his own hook. If you and I didn't absorb these fundamentals, reader, we could never become Artists, no matter how temperamental we were. I might try and try to paint Mt. Monadnock in the distance and you might try and try to draw Aunt Lucy full-face with her nose looking as if it stuck out and we couldn't, because we were ignorant of the eternal laws of value and perspective. So to Art school let us go immediately.

AT Art school, we proceed to learn all there is to know about Art (and then some) from the renowned Mr. Z, who was formerly a pupil of the great Y. But this docs not mean that Mr. Z paints exactly like the great Y. No indeed. In the first place, Mr. Z couldn't if he tried. In the second place, Mr. Z has developed an original style of his own, as every Artist must do if he is to be worthy of the name. Take, for instance, the great Y himself. He studied at various times under X, W and V and only came into the full possession of his own great powers shortly before his untimely death. Furthermore, X, W and V, before becoming the famous masters which they were, served humble apprenticeships with Lr, T and S, who taught them the techniques of those prodigious geniuses R and Q, the former of whom was P's favorite pupil, while the latter surpassed even his master O. Our statement that we are studying with Mr. Z at Art school is therefore violently erroneous. We are not really studying with Mr. Z at all. We are really studying, through Mr. Z, with the great Y and through him with the illustrious X, W and V and through them with the glorious L', T and S and through them with the mighty R and Q and through them with those unbridled giants of the neo-renaissance, P and O. It seems almost too wonderful to be true, doesn't it?

Thanks to all these great techniques, our own technique improves amazingly. Mt. Monadnock and Aunt Lucy's nose lose all their terrors. The former, with two or three of my expert brush-strokes, obediently inherits a subjective distance of five miles. The latter, with several enlightened touches of your pencil, magnificently bounds into high relief. Mr. Z is beside himself with pleasure and we arc graduated summa cum laude from Art school. If you and 1 didn't have temperament, we should now become ordinary humdrum academicians. But, being temperamental, we scorn all forms of academic guidance and throw ourselves on the world, eager to suffer—eager to become, through agony, Artists with a capital A. Our next problem is to find the necessary agony. Where is it, gentle reader?

You answer: the agony lies in the fact that we stand no chance of being appreciated—although America talks night and day and American millionaires buy more Art every year than all the rest of mankind put together —because, to our Oil Oligarchs, Peanut Princes, Soap Sultans and other Medicis, "jenyouwine" Art means foreign Art. The Art which is the most "jenyouwine" and which brings the most dollars is dead as well as imported; but (and here we have a diabolic refinement of agony) certain more elastic American multi-millionaires are beginning to purchase work by living European painters. A Chewing-gum King, for example, who formerly liked nothing but Rembrandts and Velasquez, can now be induced to fall for aScgonzac or two, or perhaps a Matisse, a Picasso, or even a Dérain. Meanwhile American patrons of Art (or rather the connoisseurs who do the selecting for these patrons and the galleries which do the selling to them) boycott P Art americain. Not only is there a complete absence of taste agent the domestic product, but once an Artist is found guilty of being a native of the richest country on earth he must choose between spiritual prostitution and physical starvation. What monstrous injustice!

Wait a moment, reader. It is silly of all these rich compatriots of ours to surround themselves with pictures which they cannot possible appreciate and do not really enjoy. Yet what have we ourselves done to merit the consideration of contemporary Medicis in particular or (which is vastly more important) of mankind in general? You will reply that we decided, for one reason or another, to become Artists; that we attended Art school, where we learned all there is to know about Art (and then some) through Mr. Z; that, having revelled in value and perspective to the extent of making Mt. Monadnock's slopes retire and Aunt Lucy's nostrils behave, we were graduated from Art school with highest honours; that, in consideration of the foregoing facts, we should be encouraged to create on our own hook instead of being driven to the wall by foreign competitors.

WELL and good—but let me show you a v v painting which cost the purchaser a mere trifle and which is the work (or better, flay) of some illiterate peasant who never dreamed of value and perspective. How would you category this bit of anonymity? Is it beautiful? You do not hesitate: yes. Is it Art? You reply: it is primitive, instinctive, or uncivilized Art. Being "uncivilized," the Art of this nameless painter is immeasurably inferior to the civilized Art of painters like ourselves, is it not? You object: primitive Art cannot be judged by the same standards as civilized Art. But tell me, how can you, having graduated from an Art school, feel anything but scorn for such a childish daub? Once more you object: this primitive design has an intrinsic rhythm, a life of its own, it is therefore Art.

Right, gentle reader! It is Art because it is alive. It proves that, if you and I are to create at all, we must create with today and let all the Art schools and Medicis in the universe go hang themselves with yesterday's rope. It eaches us that we have made a propound error in trying to learn Art, ince whatever Art stands for is what■ver cannot be learned. Indeed, the Artist is no other than he who unlearns what he has learned, in order o know himself ■ and the agony of he Artist, far from being the result of he world's failure to discover and appreciate him, arises from his own personal struggle to discover, to appreciate and finally to express himself. Look into yourself, reader; for you must find Art there, if at all.

(Continued on page 98)

(Continued from page 68)

At this you protest vigorously: but I follow your curious advice, suppose look into myself and suppose I do not find Art? What then? Do you mean to tell me that I must forever abandon my hope of becoming an Artist:

Absolutely! Art is something which may or may not be acquired, it is something which you are not or which you are. If a thorough search of yourself fails to reveal the presence of this something, you may be perfectly sure that no amount of striving, academic or otherwise, can bring it into your life. But if you are this something—then, gentle reader, no amount of discrimination and misapprehension can possibly prevent you from becoming an Artist. To be sure, you will not encounter "success", but you will experience what is a thousand times sweeter than "success". You will know that when all's said and done (and the very biggest Butter Baron has bought the very last and least Velasquez) "to become an Artist" means nothing; whereas to become alive, or one's self, means everything.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now