Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHELLO, LONDON!

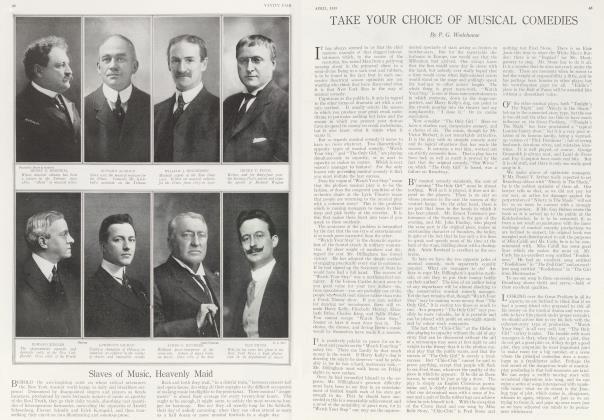

Vanity Fair's Spring Revue—At the Theatres, in the Park, Under the Picture Galleries—The Call to Farms

Campbell Lee

IT is a foggy day when the London stage is completely eclipsed. A month ago the theatres were as empty as churches. Actors began to talk like archbishops and to complain of the echo. Chocolates grew moldy in the pretty ushers' trays; spiders roped off the orchestra chairs.

Thank heaven, luck changes. Even now the profession is still precarious— as they say fishing is in the North Sea, but the haul has improved. Many new plays are popping their heads above the dramatic trenches. Bare shoulders have appeared in the stalls, and bored royalty in the boxes. The pit is full of critics and cigarette smoke. Galleries are packed, while strewn over the face of the scene are those sure signs of dramatic delight, the castaway wrappers of toffee and caramels.

Life in London seems to chatter on as usual, but her gaiety is like whiskey-and-soda medicinally prescribed; she needs it to keep her going under a load of responsibility that would ruffle a stone image. When she arrived at this truth, after the first pre-occupation of the war, theatre managers began cautiously to act. Sir Herbert Tree risked a new play called "David Copperfield." Sir Herbert took the pioneer hazards of a novelty in the teeth of revivals of everything under the sun. Sir George Alexander marked his twenty-fifth anniversary as manager of St. James Theatre by backing Mr. Besier (who was born in Java and has dramatized H. G. Wells and hence doesn't care what he does.) In a play called "Kings and Queens," it sounded like a gamble; so now was t. time for it. "Kings and Queens" spins around the theory that royalty comports itself quite like ordinary humanity in its hours of ease. As if anybody supposed it didn't!

Marie Lohr wears a crown carelessly and is particularly feminine.. Sir George Alexander, as the old prince with an eye for a pretty woman, and with a suave diplomacy is capital St. Jamesese. At the Strand Theatre, Julia Neilson and Fred Terry introduced "Mistress Wilful" of the Poor-Nelly-Charles II—Pepys—period.

Hastening to another and a more blithe Charles, London has also Hawtrey in a new play. Some day poor Mr. Hawtrey may perhaps find a play that fits him. His efforts are similar to a trial of all the tailors in Bond St. The Hawtrey latest is "A Busy Day," by R. C. Carton. It is all about a rich widow (Miss Compton) who must be saved from fortune hunters, and a "waster" (Hawtrey) who must marry money.

At a farce he laughs best who laughs throughout, and "A Busy Day," although amusing, has breaks in it. A joyous ripple is provided by a new actor whose name is Edward Fitzgerald. It has leaked out that this gentleman has been Hawtrey's business manager for years and years. Since his hit as the Irish waiter in "A Busy Day," London play-pontiffs have been staring hard at their cashiers, booking agents and even call boys and door men.

As regards the Belgians, if Germany had not included the company of Brussels' Theatre du Bois Sacre among the refugees she drove to England's shores, one more score would have gone up against her. Since these mobile players opened with "Ce Bon Monsieur Zoetebeek," with the naif Libeau in the title role, following it with "Le Mariage de Mile. Buelemans" and "La Demoiselle de Magasin," the company has established itself as one of the vivacious and delightful features of London life. Their new play, "La Kommandatur," is the first real play of the war. "Der Tag" simply succeeded in startling people by the fact that Barrie could miss it. "La Kommandatur" is a situation developing in Brussels under German rule. It is good red realism from first to last, human, witty, horrible. Fonson, the author, and a force in most of these plays of peculiarly Belgian bourgeois life, might be called a Dramatist of Dinner Tables. It is doubtful if he could write a tragedy, a comedy or a miracle play without two acts being played with the characters drawn up to a family meal, and all talking at once with their mouths full of poulet. Latin London crowds the Criterion, though the matinees are noticeably English in complexion. " It's so much easier to understand French in the daytime" is advanced. For this reason, perhaps, "Le Cloitre" an athletic monastery drama by Emile Verhaeren, the, Belgian poet, is drawing afternoon crowds.

Whatever the darkened streets have done for the evening houses, the Zeppelins, in a sense have helped the matinees. With the stripping of the picture galleries—the cellars, filled with works of art, must be quite uplifting places—one mild rival at least is dispatched The only visitors to the National or the Victoria and Albert are a few innocent trippers who look in vain for old masters and only find a few moderns discreetly hung and illuminated so that the bombs couldn't very well miss 'em!

WHILE the theatres are helping to keep things together during the crisis, as matters of dramatic interest they pale beside the movements society launches from day to day. If individuals are not giving their. art objects to a charity sale at Christie's, their houses to the War Office, or their talents to the cause, they are begging or cajoling pictures, palaces or parlor tricks out of others.

The latest originality is one of which any playwright might be proud. This is the Call to Farms. Ladies who love dogs and who have been brought up with flowers are urged to come over into Macedonia, otherwise the South Downs, and help with the lambin' and the milkin'. As all the farm workers have gone to the front, little lambkins are coming into the world without any layettes being prepared for them; cows standing in primrose pastures get about as much practical attention as the ones in the condensed milk advertisement.

It is so very serious that Lady Hustle, the Duchess of Fairelachose (old Welsh title), and other fashionables feel that English women, with their oft-sung love of country life and country crafts, should drop khaki-wool and Belgian babies and help feed the army by working the farms. Now did Mr. George Edwardes or anybody else ever have a better idea handed him? Here are one hundred pretty London girls suddenly abandoning bridge, tea at Prince's, skating at the other Prince's, flirting, bazaaring, dancing with the men-on-leave-who-must-be-amused and turning up in Sussex, this in the second act, to tackle rural economics and eugenics. Qualifications; lady has exhibited one rose at the Royal Horticultural Society, adores Mauve's sheep pictures and spends nearly every week-end in the country. Think of the costumes! Think of the Valse! Don't you see how all the men would immediately rush back to the farm, conveniently invaleeded, as the Scotties say, and the Babaas and Moo Cows and the Pink Piggies would stand forgotten in the background while the curtain went down on a barn dance of silk stockinged milkmaids and shepherdesses and irresistible Tommies?

WHAT makes Johnson break the pledge? Is it the barmaid? asks Vesta Tilley. Go to Kensington Gardens and see the model trenches and you'll understand about Johnson. Johnson, when his name is Atkins, is just now giving the drawing rooms great concern. It is almost as smart to discuss plans for dashing the festive cup from his lips, as it is to trot across the Park to see the two-by-sixgully he has to fight in—and live in. The Kensington Gardens trenches are the popular Mecca of the Parks spring crowd. If tea were served the society reporters would come and it would be called a function. Pretty girls are present in swarms with their own guides, khaki-cavaliers on leave. Tophatted groups from the clubs stand around arguing field tactics and direct the campaign with their sticks.

The crackling commands of an officer drilling one of the new Bantam Battalions (it's chic to be only five-feet-three) comes through the trees.

SOMETIMES, towards twilight, when the trench parties have gone, a little group of black-gowned women is seen walking slowly across the grass. They are the royal Princesses from Kensington Palace.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now