Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE LONDON STAGE CLEARED FOR INACTION

The Bubbling Over of the War Cauldron Has Driven Audiences From the Theatres

Campbell Lee

LONDON dramatics have shifted quite suddenly from the stage to the street.

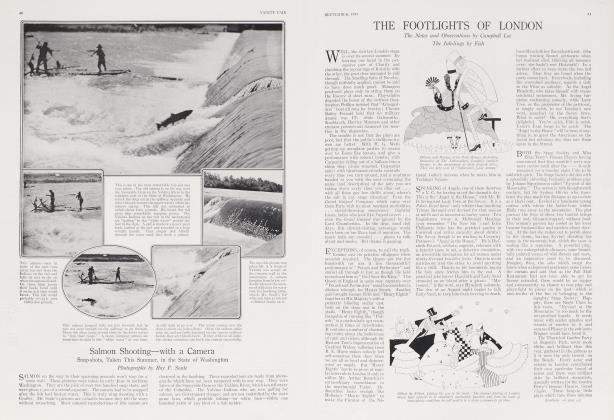

Only a few theatres are holding out against the exciting curbstone attractions produced by the war. With free spectacles of the King and Queen appearing nightly to enthusiastic crowds in front of Buckingham Palace, with Lord Lonsdale addressing the same audience from the top of a taxi, and a continuous come-and-go of ministers and military moguls at the War Office, nobody bothers about stalls at ten-and-six. Surely fate was in the war bomb that trapped twenty thousand innocent Americans in London and then gave them no place to go to but the South Kensington Museum and Madame Tussaud's Waxworks. If it were not for Miss Ethel Levey's inspiring singing of Some of These Days at the Hippodrome a good many stranded ones from the States would feel as though they never were to see home again. There is one man in London who spends his days at the steamship offices and who every evening goes to hear Miss Levey sing Some of These Days . . . sing it too, just as though she were singing it to him. His wife and four children are traveling in Switzerland and have not been heard from since the outbreak of hostilities. His two sisters are lost somewhere in the south of France. His mother-in-law went motoring in Germany late last month and has never come back. He is very worried and depressed. Of course a humorist would say that the mother-in-law-outlook was the one bright ray in his inky sky. But we happen to know that the only thing that sustains him at all is Miss Levey's song.

TWO poetic plays flashed for a moment on the British boards before the cruel reality of war put them out. One was Mr. Stephen Phillips' "The Sin of David." The other was Maeterlinck's "Monna Vanna," long under the censor's ban in England, but finally reaching a brilliant licensed performance. It is interesting that both of these plays, the premieres of the war season, should have had a military theme. "The Sin of David" is one of Mr. Phillips' archaic and ardent love stories. It is lyrically, told, and studded all over with the poet's tender little rhapsodies about the heroine's hair—not even Helleu can etch hair better than Stephen Phillips. The title role reveals Mr. H. B. Irving in a part quite cast for him. The David of the play is Sir Hubert Lisle, Commander of the field troops of the Puritan forces in 1643. He appears in the first act as a most blameless person, iron-willed, silent, cold ... a frightful out-and-outer. His first act is to condemn to death young Lieutenant Joyce who had yielded to the lust of the flesh. Sir Hubert has hardly delivered himself of this holier-than-thouism when he falls under the spell of Miriam, the disturbing young wife of a fellow officer, Colonel Mardyke. Miriam, played by Miss Miriam Lewes, frankly abandons herself to a reciprocal passion. One could hardly blame her. The Colonel is old and crabbed. Sir Hubert is exceedingly handsome in his armor. And he has a gift for pretty speeches. Very few Miriams could have resisted Sir Hubert, and this one made no effort to do so. Thereupon Sir Hubert commits the sin of David, when the ruler sends Uriah the Hittite to his death in battle so that he might marry Bathsheba, his wife. He dispatches Mardyke to the front on a fatal mission and subsequently weds the widowed Miriam. As in the Bible story there is a child. Just when their little son reaches the age when they have both transferred to him the passionate love they originally lavished on each other, the child dies. Under the stress of grief Sir Hubert confesses his crime. Miriam, cold now, repudiates him. They are eventually, reunited however, "in marriage at last of spirit, not of sense." The end is so extremely sentimental that only the critics who take their calling with great seriousness can discuss "The Sin of David" without speaking of the chee-ild. But the too-Tennysonian ending may be forgiven for the sake of the fresh and delicate phrasing and the melody of the piece.

"The Sin of David" was so very good that, for fear the public might not like it, Mr. Irving felt nervously constrained to play Cosmo Gordon-Lenox's famous one-act farce "The Vandyck" immediately after it. If this was to take the poetic taste out of the mouth it was entirely successful. It was a bit like caviare after cool, luscious melon. Otherwise "The Vandyck" is a fascinating study of a burglar who feigns insanity in order to steal the art collection of a certain gentleman. Mr. H. B. Irving was stagey as always, and, as always, extremely interesting. His flair for dramatic effect never fails him. This was as apparent in his fantastic interpretation of the thief who dances violently about the room shrieking that he is "completely cured, completely cured" as in his rendering of his last lines in David:

"Though the child shall not return to us Yet shall we two together go to him."

It was a crucial test of an actor's feeling for nuance that he could express such excessive sentimentality without being sentimental.

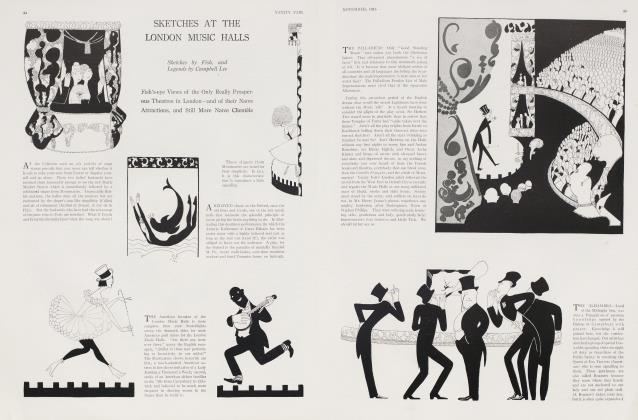

M. MAETERLINCK'S "Monna Vanna," a drama in three acts in verse, presented Miss Constance Collier in the title rôle. The besieged Li&ge brings the "Monna Vanna" motif fairly close, but there is otherwise no parallel between the Red Cross duchesses leaving daily for the front and Vanna, the fifteenth-century war heroine, who set forth clad only in her mantle and sandals and lifted the siege of Pisa. Prinzivalle, a Florentine general, holds the fate of Pisa in the hollow of his hand. He summons Giovanna to appear before him in the costume described. Giovanna accedes to his request in order to save Pisa. Guido, her husband, rages futilely. The scene in Prinzivalle's tent between Vanna clad only in her mantle of sequins and her own bright hair, and the Florentine ruler bandaged after an assassin's attack, reveals the fact that Prinzivalle had been a boyhood admirer of Vanna's, that he now loved her madly, and that he has no intention of hurting a hair of her head.

During their interview, there is an uprising against the general.

Vanna, to save his life, takes him back to Pisa maddening Mr. H. B. Irving takes him back to Pisa with her. Upon their return Guido disbelieves the story of Prinzivalle's platonics. He prepares to stab the Florentine. Vanna in a sudden realization that she loves Prinzivalle, turns about swiftly and brilliantly. Wait! She lied! She has brought back her prisoner to camp to kill him herself. None but she must have that pleasure. The key of the dungeon into which he will be thrown belongs to her. No one else must go near him. All this with reassuring interpolations to Prinzivalle. She loves him! They wiU fly together! As he is led away Constance Collier becomes for a second a great emotional actress. Guido believes her lie; "It was all a bad dream," he cries, taking her in his arms. Vanna: "Yes, it has been a bad dream . . . but the beautiful one will begin . . . the beautiful one will begin. . . ." The imagination leaps.

Continued on page 86

Continued from page 49

Pisa is painstakingly painted. All the characters assume leaning poses like the tower. Miss Collier is particularly Pisaesque. In the French version, one sees in Giovanna the strong family likeness to Lucrece and Holofernes with whom Guido proudly compares her. Unfortunately Mr. Alfred Sutro's translation is commonplace and unMaeterlinckian.

Miss Collier made a chaste and lovely picture in her mantle, her little rosy sandalled feet peeping out like Sir John Suckling's oft-named mice—but not beneath her petticoat.

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now