Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe streaming era has presented a vexing Hollywood question: What, exactly, is a movie?

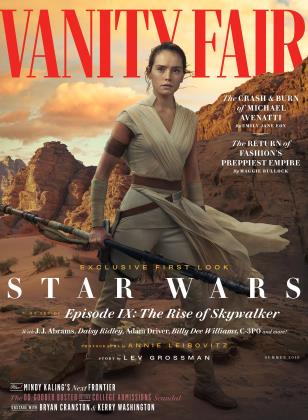

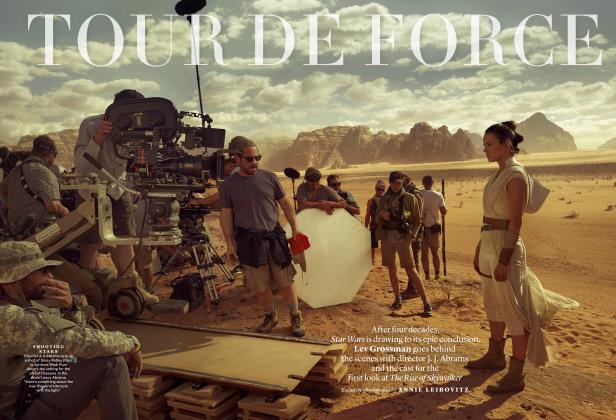

Summer 2019 Nicole Sperling Ben WisemanThe streaming era has presented a vexing Hollywood question: What, exactly, is a movie?

Summer 2019 Nicole Sperling Ben Wiseman View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now