Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

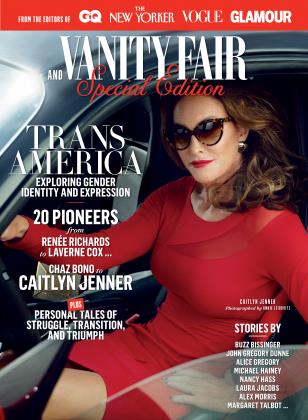

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBUZZ BISSINGER traces transgender history: the advances, the anguish, and the road to acceptance

August 2015 Buzz BissingerBUZZ BISSINGER traces transgender history: the advances, the anguish, and the road to acceptance

August 2015 Buzz Bissinger View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now