Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDAVID IS GOLIATH

Recording mogul David Geffen is part enfant terrible, part last tycoon— and Hollywood has never stopped talking about him. The MCA-Matsushita deal made him the richest man in town, he bought (but doesn't live in) Jack Warner's old estate for $47.5 million— and he's still on a tear. PAUL ROSENFIELD reports how the street-smart kid from Rrooklyn got everything he wants

From the March 1991 issue.

'The real way the rich are different from you and me," says Fran Lebowitz, "is that they have more options. Take David. Everything about him is unlikely. Everything." Says Cher, "Everything about Dave is a duality."

David Geffen is the man who last year bought Jack Warner's estate—the last great Beverly Hills house with grounds—and this year is talking about selling it. Before he moves in. And yet, he's overseeing construction of the outdoor marble kitchen that will separate the pool from the tennis courts. He's the rabbi who's also the fixer. Mario Thomas went to him for advice about whether to marry Phil Donahue. Michael Jackson, on the other hand, went to him for advice when he wanted to replace his lawyer, his manager, and his record-company president. "David is the most perfect combination of business and artist," said Geffen's friend restaurateur Peter Morton. "Unlike almost anybody else, he functions in both worlds." Another duality.

Geffen is the tycoon who dresses like a hip kid. He is also the man who went from being "in love with Cher to being in love with Mario Thomas to being in love with a guy at Studio 54." That's a duality that Geffen recently elaborated on. "I date men and I date women," he said one afternoon in his New York apartment. "What Woody Allen said was true. Say what you will about bisexuality, you have a 50 percent better chance of finding a date on Saturday night."

Of course, even then you have to be lucky. And that's another Geffen split people talk about: Is this Brooklyn-born billionaire lucky or is he smart? "Luck is just about being in the traffic," he said simply. "And I've stayed in traffic for a long time now. I've been wealthy my entire adult life. But I'll tell you one thing. I wouldn't rather be smart than lucky. I'll take it however it comes. Because I'd rather win than be right."

Hollywood's favorite Christmas saga for 1990 wasn't Godfather III as expected. It was Geffen. Suddenly David had become Goliath. In one week in December, the boyish mogul had been considered for the cover of Newsweek, turned down the cover of GQ, and accepted the cover of Forbes.

Yet a year [before], when Vanity Fair selected Geffen for the decade-end, media-themed Hall of Fame, cynics asked, Why? The recording-industry wizard may have successfully crossed over to the movie business with Geffen films (Risky Busimss, Beetlejuice)—but so what? Sure, he owned a third of Cats, and never had a flop on Broadway. And yes, his Geffen Records put out the chart-busting Aerosmith and Guns N' Roses, making his company the largest independent record label in the world. But there were other media stars who seemed to have a larger claim.

Twelve months later nobody would ask "Why Geffen?" In his extraordinary 1990 double whammy, he sold Geffen Records to the entertainment conglomerate MCA for 10 million MCA shares, worth $540 million, and eight months later, when MCA was sold to Matsushita for $6.1 billion, his shares were suddenly worth $710 million. With his extensive California landholdings (shopping centers, apartment houses), his modern-art collection, his film company, and his other investments, Geffen has suddenly become a new kind of celebrity: he's Hollywood's first crossover business star.

Geffen is a unique tycoon in a town of tycoons: he combines the business strengths of a Mo Ostin or a Michael Eisner with the creative gut of a James Brooks or a Barbra Streisand. What made David Geffen David Geffen and not MCA president Sid Sheinberg is that he really is friends with the talent that made him his fortune. He can talk music and movies and theater with creative artists, and he understands their process. Sheinberg can't do that; he can only do the numbers. But from early on—as founder of Asylum Records in 1970 through his appointment as vice-chairman of Warner Bros, in 1975 through his re-emergence in the music business with Geffen Records—Geffen has been able to do the numbers too. Even the celebratory $47.5 million purchase of the Warner house last spring, which many saw as a manifestation of a possible Mogul Complex, may turn out in the end to be just another smart deal.

The ink on the obituaries for Jack Warner's widow, Ann, was barely dry before her daughters, Barbara and Joy, gobbled up Geffen's offer as if it were a gift from above. They sold the house lock, stock, and antique barrel to the first bidder. "I bought it because I got seduced by the deal," Geffen says, sighing. "I get caught up in the gestalt of something. I got caught up in the Jack Warner of it all. He was this legend to me, and this was his house. Now I'm worried about how I can live in this house," he says. "I never spent the night in it, and I likely will not."

So it's an investment? "Ten acres, in Beverly Hills, with all the possessions, for $47 million," he explains. He sold off $9 million worth of antiques and collectibles last fall and still has some more to unload. And he probably could turn around and sell the house at a profit, this minute. "The worst thing that can happen," Geffen says, "is that I'll make money.'

On the last Saturday of the summer, ten days before the MCA-Matsushita deal was leaked in The Wall Street Journal, Geffen had what his lawyer, powerhouse rock attorney Allen Grubman, calls "David's ultimate reality check." Late on that cool morning in New York, Geffen and Grubman were on their way to SoHo for lunch; instead they drove to Borough Park, in Brooklyn, where both men grew up.

Grubman remembers Geffen saying plaintively, "I want to show you where I was bom." So they went to the CHIC CORSETS BY GEFFEN storefront on Fifteenth Avenue, where his mother had made bras for other women, and then they went to his boyhood apartment house two blocks away. They went to Coney Island and walked to the end of the boardwalk; they told stories for almost four hours. Shortly after Gmbman dropped Geffen off back at his Manhattan apartment, Gmbman got a phone call from Geffen.

"David said, 'You know, Allen, I'm never going to be the same again. Today we remembered where we came from. All the struggles. We have a tendency to forget.' "

"WHAT HE KNOWS BETTER THAN ANYONE IS WHO A STAR IS, AND ISN'T.''

"DAVID WAS SIMPLY DOING WHAT DAVID DOES-GOING FOR THE CURVES OF LIFE;

His mother, Batya Geffen, took in sewing during the Depression and then saved up enough to open her cor set shop. If David's father, a patternmaker, was peren nially out of work, Batya more than made up for it. What people always miss when they tell the David Geffen Story is not only that Batya bought the building she worked in but that she also became a landlord. So even early on, David saw money being made in the family. It was not like Neil Simon, who wanted to succeed to support his mother. Geffen, in fact, may have needed to outdo his. He didn't see Batya (who died in 1988 ) as tragic on any level; he found her life echoed in the "tons of biographies" he began reading as a teenager. "All of them said the same thing. Your life is your work. And she was living proof."

Geffen graduated from high school with a 66 average, in the bottom 10 percent of his class. "But King David has golden hands," Batya Geffen told her son. "King David can do anything he wants. So you are not a good student. So?" Geffen dropped out of two colleges. Then he learned the truth at twenty, at the William Morris office, where he had started working in the mailroom before becoming a junior agent. Jerry Brandt, then head of the agency's music department, told him, "You are barely twenty years old. And you're being a jerk. Is Norman Jewison going to waste his time signing with you? You should work with people your own age." That meant the music business.

So in 1968 he took a job as a music agent at Ashley Famous, working with such acts as the Doors and Peter, Paul and Mary. It quickly became clear what his role was: Talent Scout Extraordinaire. According to longtime Billboard columnist Paul Grein, "Clive Davis had the best ears in the music business, but Geffen had the best instincts about people."

The singer-songwriter Laura Nyro had been booed off the stage at the historic 1967 Monterey Pop Festival. Although Geffen hadn't been there, he later heard a tape and decided "anyone who sounded that good and had such a public disaster had to have something going for her." He went to Give Davis, at the time president of Columbia Records, and, Davis remembers, "talked me into Laura Nyro." "This was the high point for Laura Nyro, and the beginning for me," remembers Geffen. Soon he left Ashley Famous and went out on his own ( with his secretary, Elliot Roberts) and became manager for the musicians he discovered and developed.

Nyro turned into Geffen's first hit performer, and when he engineered the sale of her publishing company, Tuna Fish Ltd., for $4 million in 1969, each got half. "I loved Laura Nyro, and I wound up not speaking to her," Geffen says. He gets uncomfortable when you mention the way Nyro dropped him after the deal was done; the speculation is that she wasn't happy with the fifty-fifty split of the proceeds. Along the way she sent him a revealing "Dear David" letter: "Tell me that we can go ahead with the deal, be done with this nightmare, and you and I be soulmates to each other." They haven't spoken since.

Geffen moved on to Joni Mitchell, who was at the time traveling and doing one-nighters. The songstress and Geffen went on to live together platonically for a time in Bel-Air, but, more important, Geffen ended up helping shape her first (and best) four albums.

The reputation was begun. An eight-by-ten glossy that Jackson Browne sent to Geffen with a demo tape so impressed his secretary that she made her boss listen. Geffen drove out to Echo Park to the shingled boardinghouse where Browne lived, and wound up joined at the professional hip of the singer-songwriter. Upstairs at Browne's house, he met some guys who called themselves the Longbranch Penny Whistle. Geffen invested $5,000 in them, and renamed them the Eagles. Other early Geffen acts included Jesse Colin Young, the Association, J. D. Souther, Linda Ronstadt. He was managing a lot of artists, and was always making and doing, running from Monday amateur nights at the Troubadour to midnight recording sessions at Capitol to being backstage whenever anybody needed him. "David Geffen in back of me is what I want," Jackson Browne told the press. "He's always there."

But being there eventually began getting on his nerves. As a favor to David Crosby, Geffen smuggled an envelope of marijuana from a girlfriend of Crosby's in London to New York, where Crosby was singing at Carnegie Hall. David got busted and booked at the airport, and his older brother, attorney Mitchell Geffen, had to get him off. But it was Crosby who rankled Geffen the most. "Where the fuck is my dope?" the rock star asked the manager. David Geffen didn't like to be talked to that way. And soon he was out of the management business.

Ahmet Ertegun, the head of Atlantic Records, is the first name Geffen mentions when you ask him about mentors. When he and Geffen met, in - 1968, Ertegun knew what it meant to be a young man in a hurry (he had started Atlantic when he was only twenty-four). Geffen first tried (unsuccessfully) to persuade Ertegun to record Jackson Browne. "You can make a fortune," Geffen insisted. "David, have a fortune," Ertegun replied. "Why don't you make the fortune?" Ertegun suggested Geffen start his own label, and helped him form Asylum Records.

In his Rockefeller Plaza office today, Ertegun smiles at the memory of the young Geffen. Through the years they've tangled and tom each other apart, but they've remained friends. I ask Ertegun how Geffen was, at twenty-four, different from every other Sammy Glick in the record business. "Well," says Ertegun, "a lot of people have ambition. Y>u see them every day. But very few combine resourcefulness with a willingness to work, plus the intelligence." Capitol/EMI Records president Joe Smith puts it more tightly: "David was a laser beam from day one."

It's easy to ask disaffected people in the music business about Geffen's ruthlessness; they always see distortions and exaggerations. But Ertegun's nose was never out of joint, so it seemed a fairer question to ask him. "In our business it's not unusual to be ruthless. It's not ruthlessness in order to ruin people, or cause bodily harm. People just try to get what they want at any cost. And, by the way, the movie business is the same. And Wall Street is the same. And Detroit is the same."

"Ahmet is right," agrees Geffen. "Every business has a dark side. I had to leam this over time. I wasn't as smart when I first knew Ahmet as I am now," Geffen says.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 104

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 55

Was he brash?

"I was brash. I was a lot of things. If you see things in your life that are not working for you, it's best to let them go like heavy baggage. In the early years with Ahmet, I was often competitive and angry and disappointed."

And combative. After music attorney Brian Rohan had an altercation with Geffen at a luncheon at the Beverly Hills Hotel, Rohan got telegrams from all over. Reached in San Lrancisco, Rohan remembers "being very angry at David about a business deal—a signing of an artist I represented. Give Davis was hosting this lunch, and I saw David sitting there. We were old friends, but I felt he dicked me around. I'm large and Irish and I said something to David very quietly, and he fell back over a chair. Sue Mengers was sitting next to him, and she and some other people took dives under the table."

"It's extremely hard to blow David off when he wants something," says one prominent business manager. "He's obsessed. He was obsessed with Laura Nyro, he was obsessed with Joni Mitchell, he was obsessed with the Eagles." Geffen explains the obsessiveness this way: "Wherever I walked in 1970, there was somebody talented. The sixties had been such a powerful decade. And there were all these people who hadn't happened yet. Whether it was Steve Martin or Jackson Browne. And I couldn't believe nobody else wanted these people—that I could just pick them up for nothing. I would be impatient about wanting these people, and other people suffered the impatience."

I repeat to Geffen a line of one of his Hollywood mentors, agent Irving ["Swifty"] Lazar: "What Geffen wants, Geffen gets."

He smiles in a hesitant way that says, Not always.

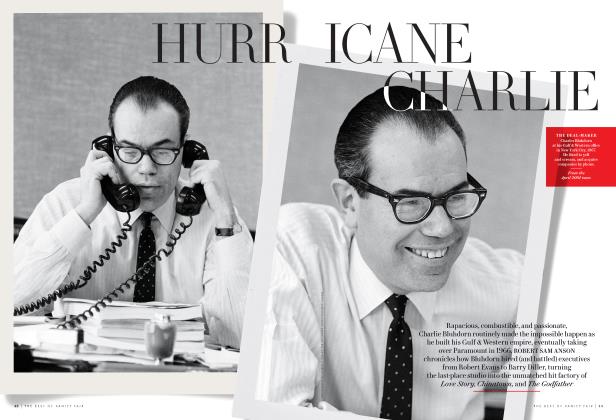

Within two years of its founding, Asylum was gushing oil, and Steve Ross, the mighty head of Warner Communications, asked Geffen to name a figure for the label. Twenty-four hours later, Geffen sold Asylum for a too low $7 million, and it merged with Warner's Elektra label. (The Eagles' next album, Hotel California, sold more than 10 million copies, and Warner's made more than $15 million in profits.) He immediately dropped 90 percent of the acts on both labels; according to Geffen, thirty-eight of the forty albums released by Elektra/Asylum the following year were hits. From the first, Geffen went after the solidest people in the not rock-solid music business. "Only, he never attended a staff meeting once in four years," claims Joe Smith, who replaced him at Elektra/Asylum. "And that's not a rap, by the way." Geffen was including himself when he characterized those days as "a group of nerds who were allowed to be who we were. There was angst, neurosis, turmoil... I love nerds."

He also loved talent. He was smart enough, tuned-in enough, to have understood what people like Ronstadt were talking about, even when they babbled. He gave his artists time to develop. He likened himself to a baby doctor—"I assist," he says—but he was more than that. Like Goddard Lieberson, he was a talent master, the coach who corralled everybody. "It was all pure instinct," says Bruce Springsteen's manager, Jon Landau, who calls Geffen his "rabbi." (Indeed, there is something almost ecumenical about Geffen when he talks about "eliminating for artists the danger of being cheated and abused.") Although Geffen wasn't a poacher, he wasn't above raiding other companies' ranks. He got the Band to leave Capitol Records, just as he got Bob Dylan away from Columbia. When Geffen wanted to sign Dylan, he "not only bought a house near Dylan's at Malibu," says Brian Rohan, "he also spent every day there with Dylan." He followed him to Europe. And he signed him.

After ten years in the music business, though, Geffen became restless. To keep Geffen happy (and also because Geffen asked him to), Ross upped the ante for his gifted protege: he gave him a shot at the movies. In 1975, Geffen, for better or worse, became vice-chairman of Warner Bros. Pictures. It was the beginning of the end of a boy's dream.

Growing up in Brooklyn, Geffen had been entranced by the movies. He sat through double features for twenty-five cents at the sky-blue Barwood. He remembers going to Radio City Music Hall to see the Rockettes, and that night composing his first Oscar acceptance speech. He knew every picture in Debbie Reynolds's four-picture deal with Metro; he knew Debbie was seeing Glenn Ford, who had been dumped by Judy Garland. He knew everything. But two decades later, it seemed he didn't know enough. His experience at Warner Bros, was a horror show from the first week.

Although Geffen did green-light some successful films in his year at the studio (Oh God!, Greased Lightning), he didn't care about or understand the corporate bureaucracy. He sent memos without carbon-copying them, and got himself into political hot water all over the lot. While Fox chairman Barry Diller—Geffen's friend and soul mate since they met in the sixties in the mailroom at William Morris—succeeded brilliantly in the shark-infested studio waters (he ran Paramount before Fox), he thinks that "companies are too inefficient, in the most honest sense of the word," for David. Geffen sums it up himself by saying, "I don't have the personality to be a corporate executive."

His experience with Robert Towne at Warner Bros, was perhaps his worst. Geffen agreed to bankroll the $6 million needed to complete Personal Best, Towne's directorial debut. Apparently Geffen thought (as was the case in the music business) that backing meant control, and Towne wasn't having any, complaining to everyone about Geffen's long, long phone calls at night. ("So he could have hung up," retorts Geffen.) Had Personal Best been a hit, all would have been forgiven (probably). But the movie turned into an overpriced—if intelligentbox-office dud, and ended up costing the studio $16 million. Warner Bros, ate the negative cost, and Geffen and the company wound up being sued by Towne for $155 million for breach of contract. The Towne affair was probably the last straw at the studio. Only a year after he accepted the job, Geffen left Warner Bros, by mutual consent, although he maintained a movie-production deal with them that he has to this day.

Looking back, Geffen becomes uneasy at his disillusionment during the Warner period. "Fifteen years ago I wasn't as smart as I am now. There were things I had ambitions for, which, if I had gotten, I would have died under the weight of. Today, if you said to me, 'Hey, would you run a movie studio?' I would kill myself. I can't think of a more honible job.

"I'm not saying that anyone in the world would hate those jobs, but they're really hard jobs. It's overwhelming. You never get to say, 'I won, and now I can rest.' You just have to make the next movie, and the next one, and the next one. Anybody who's good at these jobs has more failures than successes, because more movies are unsuccessful than successful. And failure is the most painful thing in the world."

Second most painful. The year Geffen left Warner Bros., he was incorrectly diagnosed as having bladder cancer, a catastrophe which left him believing he was dying and also led him to leave show business for several years. "I went in for a cystoscope, because I was peeing blood. When I woke up, it turns out they removed a tumor. And it was malignant, they said. I never went for another opinion, because the tumor had been removed."

Geffen taught at U.C.L.A. and Yale for four years and spent a lot of time in New York at Studio 54 ("I began wanting to get laid a lot"). Then, four years after the original diagnosis, "they rechecked the slides during a biopsy, and discovered the tumor had been benign." Geffen is dispassionate in the retelling of the story, although for years he couldn't talk about this period of his life. "My mother got furious. She wanted me to kill the doctor. Me, I looked at it like 'Well, I get to go back to work.' Like 'Oh, you're well, you won't lose your bladder, you'll live.' "

By 1980, relieved of the cancer scare and bored with his days at Yale and nights at Studio 54, Geffen was antsy to get back into business. He had amassed more than $20 million in California real estate, and the seventies were over. A soul-searching trip to Barbados with Paul Simon and TV producer Lome Michaels prompted Geffen to go back to work; Simon suggested he "just begin." Within two days, Geffen lined up backing for his new company from his former Warner's boss and father figure, Steve Ross.

What was unusual was the backing itself. A Los Angeles entertainment attorney calls the arrangement the "hat trick of all time. Essentially, Warner's financed Geffen Records, almost interest-free. David put in very little money except direct expenses. Warner's funded Geffen Records in a distribution arrangement that left Geffen owning all the assets of his company."

The start-up was shaky. Geffen overpaid for the first two acts—Elton John, whom he courted lavishly, and disco diva Donna Summer, to whom he paid $1.5 million for an album that came out when disco was on the wane. Then, out of the blue, Yoko Ono called, and within months Geffen Records was recording John Lennon's Double Fantasy. (Ono and Geffen quickly became friends; he was in fact the only friend with her throughout the night Lennon was murdered.) Double Fantasy was Lennon's last album, and Geffen Records' next couple of years were nobody's fantasy.

Patrick Goldstein, the Los Angeles Times s rock columnist, wrote the following item in 1982: "Question: What's the difference between Geffen Records and the Titanic? Answer: the Titanic has better bands." A few nights after the item appeared, Geffen ran into Goldstein at a premiere at Mann's Chinese Theatre and screamed at him. Dozens of people were riveted to the display. Geffen had been predicting that his label would soon be one of the most successful independents in the world. And he would not be proved wrong.

The label did not by any means become what it was to become by the late eighties, but it was succeeding, even without friends and former artists like Jackson Browne and Linda Ronstadt. Although Geffen can be a brat, and petulant, he also learns hard lessons, and what he learned by 1980 was that he was no longer a wunderkind. He found three of the best A&R men for Geffen Records—John David Kalodner, Gary Gersh, and Tom Zutaut—and gave them complete autonomy. "When everyone had written Aerosmith off, mostly because of drugs," recalls Kalodner, who signed the group, "it was David who told me, Abu should go for this.' Here was a group that was washed up, and David invested a million dollars in them.

What he knows better than anyone is who a star is, and isn't. In 1986 everyone said I was out of my mind to want to record Cher. David said, 'She has nine lives. Go do this.' It took me two years to get Nelson's album right [from bandmates Matthew and Gunnar Nelson, twin sons of performer Ricky Nelson], and David said, 'Stay with it. They're stars.' But he doesn't second-guess you.

"You don't go to him for musical evaluation," says Kalodner; but then again, Geffen doesn't expect you to. He redefined his role a while ago. "At the age of thirty-three, I stopped signing acts," Geffen says. "I don't hold myself out to be a talent scout any longer. I'm too old. But let me say this: if I'm not smart enough to know when to walk away, I'm sure somebody would tell me. Because I'm available. People walk in here all the time and say, 'Schmuck, what are you doing?' "

"Almost from the start," recalls an industry observer who has also done business with Geffen, "David left the day-to-day to his employees. People compare David to Bill Paley, but he is actually the opposite: Paley never cared about his executives, whereas Geffen saw to it that his employees became very rich. The way it works is, they call David when they need him, and he steps in."

And sometimes he steps in when they don't call him. For example, last year, when Geffen was lunching with Island Records chief Chris Blackwell, Blackwell brought up his displeasure with Geffen's signing of the controversial group the Geto Boys. Geffen hadn't the foggiest idea what Blackwell was talking about. When he got back to the office after lunch, he went right to the president of his record company, Eddie Rosenblatt, and asked about the Geto Boys. When Geffen heard the offensive demo tape, he told Rosenblatt to unsign the group. It meant Geffen Records lost a lucrative distribution deal with the Geto Boys' producer, Def-American Recordings, and it meant the loss of a half-dozen solid Def-American artists for Geffen. No matter how much Geffen trusts his team, though, it is his company, and he takes the heat when one of the label's groups stirs up controversy (as with the scatological Guns N' Roses and Andrew Dice Gay, both Geffen acts).

So Geffen has ultimate veto power, but most of his energy still goes into attracting and promoting. Example: A former PolyGram executive remembers one summer when "David went to Europe to pursue Peter Gabriel while we had him under contract. We were waiting for Peter to return from Europe, but David beat us to him. There's a bright star over this planet watching over David. He's lucky, apart from being smart. He's not even a great liar; he's a good liar, not a great one. But he's relentless." Geffen also went after and got Ric Ocasek, lead singer of the Cars. "We had the Cars under contract when I was still at Elektra," remembers Joe Smith, "and David wanted to sign him as a solo act. And I blew up. I decided to sue David and his artist and his record company. Then it hit me that David had to win—because Steve Ross would have to pay both attorneys' fees [since Warner's owned Geffen Records' distribution rights as well as Elektra], When I told David I was backing off, he said—and this is pure David—'You're doing the right thing.' By the way, Ocasek's album stiffed," Smith adds, "which usually makes me unhappy, but in this case didn't."

Geffen Records was eclectic, not folk-rocky like Asylum, and it became a true eighties label. Its huge success came late in the decade with the advents of Whitesnake and Guns N' Roses. Then Cher resurfaced as a recording artist, and, perhaps most remarkably, Aerosmith had its comeback. If that weren't a strong enough roster, add young acts such as Nelson and Edie Brickell and New Bohemians.

Geffen also went on to Broadway, after one of those "out-of-the-blue calls" from old friend Michael Bennett. He co-produced Dteamgirls, which resulted in the largest-selling original-cast album since Hair; next came the one-third share in Cats, netting him $6 million a year. Meanwhile, most of Geffen's films were coming out hits, such as Risky Business, After Hows, Lost in America, Beetiejuke.

By the end of the eighties Geffen was so influential and Geffen Records such a success that he was a member of what author Fredric Dannen (HU Men) called The Troika: Geffen; Columbia Records' then president, Walter Yetnikoff; and MCA Records' then president, Irving Azoff. "David is my idol," says Azoff, who [would become] the president of his own label, Giant Records. But the two of them are on-again, off-again. "Currently I'm David's biggest fan. How else can you feel about a billionaire?" So they're on-again? "We've been on-again for five years at least. The last time we were off-again was when he got mad when I signed Boston, and I got mad about something to do with Don Henley. But David forgives as quickly as he gets mad." Azoffs laugh is almost smug. He likes putting himself at Geffen's level; you can hear it in the smooth, relaxed voice.

Azoff may not be threatened by Geffen, but others not at Azoffs level are very threatened indeed. Geffen is at a point where he may be too powerful to have enemies: when you call people in the music business about Geffen they respond in one of two ways—either they say nothing or they check first with Geffen before talking.

Except for Walter Yetnikoff, the former Columbia Records president who was fired by Sony last year in a bloody, almost operatic scenario. One version has Geffen as the instigator of Yetnikoffs demise; the thinking was that Geffen suggested to Yetnikoffs top stars—Bruce Springsteen and Michael Jackson—that they show public displeasure with Yetnikoff. Through small leaks to the press, etc., Sony would get the message. Yetnikoff and Geffen, like Azoff and Geffen, and Azoff and Yetnikoff, are prone to what one onlooker calls "major rights and major making-ups." The same source says she's "never met anyone who wanted to be David's enemy." This woman never met Walter Yetnikoff.

"Isn't David kind of boring at this point?" Yetnikoff wanted to know. I asked him about his firing, and whether he thought Geffen had had anything to do with it. (Joe Smith had told me, "They'll all deny it.") Said Yetnikoff, "David says he had nothing to do with it. He called me a month ago, just as the MCA deal was closing, to tell me he had nothing to do with it. But I have indications he didn't work with completely clean hands." Yetnikoff paused. "This reminds me of a passage from Shakespeare. Methinks the lady doth protest too much." Yetnikoff paused again. "When David called me to kvetch, he said, 'Walter, your problem is you think money is the root of all evil.' And I said, 'Me, David? I'm Jewish ... The root of all evil, David, is fear. And what can I tell you? You're a frightened guy.' "

So is Yetnikoff scared of Geffen? "Nah. We're on-again, off-again. It depends on the lunar eclipses." Would Yetnikoff work with Geffen again? "Very carefully. But, look, I'm an iixelevancy in the life of David Geffen." So no hard feelings? "If I was mad-mad, I'd be screaming much more."

One day in his office, I ask Geffen point-blank about his enemies. "I don't believe I have a lot of enemies," he says. "If I do have them, I'm unaware I have them. I'm not involved in huge struggles with people all the time. Do you mean what Irving Azoff said in Newsweek? About me punishing my enemies and rewarding my friends?" Geffen begins to turn red. "That's about Irving, it's not about me. All right, it's true, I had a difficult time with Walter Yetnikoff. But not because I was mad at him. He was mad at me for some reason. But I was not unique in that he was having problems with me. Walter had problems with lots and lots of people." So Geffen didn't get Yetnikoff fired? "Ridiculous. Walter slit his own throat. I did not put words in his mouth to cause him to have all these problems. Besides, how could I be responsible for what Sony— a company run by people I've never met—does about management? It's insane to think it. Insane."

"He couldn't get Walter fired and he couldn't get me fired," says Joe Smith, "but he can plant doubts in people's minds."

And he can enjoy the drama when it finally happens. The day Yetnikoff was fired by Sony, Geffen reportedly called Azoff at seven A.M. and greeted him with the words "Ding-dong the witch is dead."

Eighteen months ago, Geffen was sitting comfortably, running his company, when the Time-Warner merger happened. Without anyone cluing David in. Geffen claims Time Warner chairman Steve Ross had "always promised me he'd buy the record company." Insiders believe Geffen had taken Ross too literally. But for Geffen, it was a given that Ross would take care of him during the merger by buying Geffen Records, and when it didn't happen, he began to listen to bids from Paramount and Britain's Thom-EMI, among others. When the one-page fax came from MCA president Sid Sheinberg, last spring, suggesting a buyout, Geffen was ready to listen. Four days later, a deal was cut, giving Geffen his 10 million MCA shares.

"David wasn't listening to hieroglyphics or soothsayers," says Irving Lazar. "David was simply doing what David does—going for the curves of life." In other words, he was gambling on MCA's being sold to another company (probably a rich Japanese one) and his MCA shares' being bought at a premium. "He knew Lew [Wasserman, MCA's chairman and C.E.O.] was getting on in years. He knew there were grandchildren, and trusts, and his hunch was that Lew was about to sell," says Lazar.

"I just think things through, and I make a lot of correct decisions," reasons Geffen. "And sometimes, once again, I'm lucky. It was smart to sell to MCA, but it was lucky that the Japanese bought it eight months later. I had nothing whatever to do with it. The focus is only on me because I was the major beneficiary financially. And because sometimes two and two and two makes ten. And right now I'm looking like a two-and-two-makes-ten."

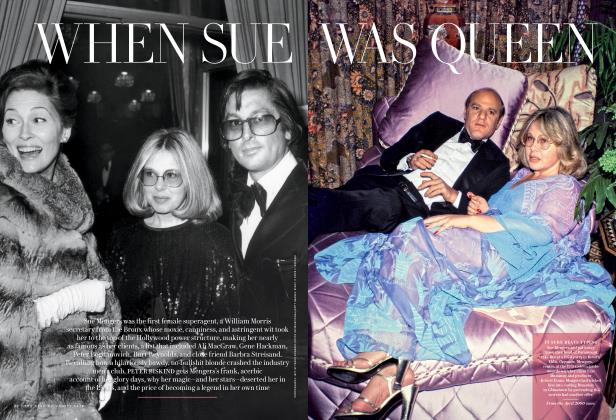

It was just another evening with the folks, Holly wo o d - style, circa 1975. Natalie Wood was there with her once and future husband, R. J. Wagner. Cher was there with [magazine eminence] Henry Gmnwald, who had just put her on the cover of Time. Michelle Phillips was with Jack Nicholson and Warren Beatty. In the comer at Sue Mengers's teakwood bar, Barbra Streisand mingled with Dyan Cannon, who was in a brocade caftan exactly like the one Marisa Berenson was wealing. George Segal was in a tuxedo.

David Geffen, as always, was in jeans.

There was so much ambition in the house that night you almost forgot the party was for Princess Margaret, the visiting royal who'd asked the English critic Kenneth Tynan to see to it that she attended a real Hollywood partyTynan went to the hostess of the moment, Sue Mengers [see page 28], "because he knew I could attract stars. Which I could. But what I couldn't do was to get the guys to wear black-tie. This was at the height of my social obsessiveness, the pinnacle of my social striving. Every star wanted to come, and I decided I had to include David." Mengers paused to let the scene emerge. "It was buffet, it wasn't seated, so you couldn't hide anyone. And as we escorted Princess Margaret in, the first face we saw was... David in the jeans, holding a glass of wine, and looking like 'Who cares?' And I paled. I thought, My God, can I get away with saying it's De Niro? So it was my worst nightmare. I mumbled David's name, and I'll never forget it. David lifted his glass and said 'Hiya!' " Sue Mengers shook her blond head in disbelief. "And the thing is I don't know if he'd do it different today. Hiya!"

He probably wouldn't. The thing no one can believe about David Geffen is how simple his life really is. He may commandeer the MCA jet at will and he may own the Warner house, but after all these years he still wears his jeans and sneakers everywhere and he still lives in the two-thousandsquare-foot beach house he bought in 1973. Although he was a version of a hippie in the sixties and sybaritic in the seventies, in the eighties his life was pared down. He takes exceptionally good care of himself (his trainer comes every morning), and all of the fat in his life has been trimmed away. (Literally: he went on the Pritikin diet last year. And figuratively: he wastes no time on anyone he's bored by.) Perhaps the simplicity is just the luxury of the truly rich. But it's more likely a part of his surprising, soul-searching human side, which is less well known than his compulsive business side: he has been a pioneer in California's self-help and spirituality movements since the seventies—he's done est [Erhard Seminars Training] weekends, Lifespring retreats, endless psychoanalysis sessions, and the fervid Course in Miracles, presided over by the gum of the moment, the beatific Marianne Williamson.

Simplicity and a search for the spiritual haven't meant a lack of intensity, however. According to his old friend Carrie Fisher, "David has the kind of intensity you usually associate with a drug addict. Only David doesn't do drugs. He's too reality-based. His favorite line is 'What are we pretending not to know here?' "

'There's not a centimeter of fat on anything that he's interested in," says Barry Diller. "He has such an extraordinarily precise ability to focus. He's able to look at what interests him with the most exact gaze of anyone I've ever known. It's as fine a measurement system as exists. That precision is a kind of genius."

"What separates David from other businessmen I've worked with," says antiquarian Rose Tarlow, who's redoing the Warner house with him, "is that I usually have to explain things three times. But David, within the span of a sentence, always knows what you're talking about. He'll say to an engineer, 'Indulge me. This is a crazy idea,' and it's the right solution. You can never outsmart him. Ever."

Geffen's smarts have led him to have an unusual number of close relationships with a lot of other smart and powerful people, especially the foui' friends who make up the David Geffen Best Friend Clique: Calvin Klein, Diller, talent manager-producer Sandy Gallin, and Disney honcho Jeffrey Katzenberg. (Designer Diane von Furstenberg fits in there somehow.) All four men claim they speak to David "365 days a year wherever in the world we are," as Katzenberg says. Disney's studio head calls Geffen "my best friend and also my harshest critic." (Geffen has so many friends that inevitably some of his closest are themselves enemies. For example, David Geffen may be the only man in Hollywood to have a close relationship with both Katzenberg and his arch-rival, MCA's Sid Sheinberg.)

Yet despite the family of friends that he's come to surround—and protect—himself with, Geffen is visibly and resolutely a single man, a solo act. Three or four nights a week he's home alone watching movies in his Malibu screening room. The private life he does have he feels should be just that. Geffen is not like some married producers in Hollywood who lead double lives, pretending to be straight; he shows up at dinner parties with whomever he's seeing at the time, whether a man or a woman. "I have not kept any secrets," Geffen says. "There's not a person who does not know my story."

Referring to threats from certain quarters of the gay press that they would "out" Geffen, he says, "No one can threaten me with exposure of something I'm not hiding." The fact is, sex is a nonissue, and a non-problem. And nobody's business.

One day Geffen sat in his Los Angeles office, took a letter opener from his antique table, and flipped it onto the Berber caipet.

"Try to pick it up," he said.

I reached down and picked it up.

"No," said Geffen. "I said try to pick it up."

Again I tried. Again Geffen said, "No, I told you to try. You see, you can't try. You either pick it up or you don't. That's my philosophy of life. Trying doesn't count." (This was pure est.)

Today Geffen sits in the office in his Eames chair, with his Evian bottle, and his view of Sunset Boulevard, and his daily life continues almost without change. Informed sources say he will stay put—for a while, anyway. His influence has grown enormously, and he has his usual agendas. There's significant buzz in the music business that Geffen wants Arista president Clive Davis to join MCA "because MCA has no presence on the East Coast," according to one L.A. attorney. "So David is giving Give the 'double-double sincere.'" (Davis says he "can't comment," but observers predict he will join MCA and bring Whitney Houston with him, since she reportedly has a "keyman" clause in her Arista contract which says that where Clive goes Whitney goes.)

Other informed gossips say Geffen is occupied trying to woo George Michael and Bruce Springsteen. He is also keeping a parental eye on his own artists' careers, too; although Aerosmith is thriving and nobody thinks Nelson is a oneshot, one industry veteran rates Whitesnake as "history," Cher as "fragile," and Edie Brickell as "a dead issue."

But the larger question is: What role will Geffen play next? What more can he do? Many think that with no other business planets to conquer, he will try to reinvent social Hollywood all by himself, playing the "A" host, living a mogul's life in his new mogul home. Not since the Sunday salons of the sixties and seventies at the Malibu house—ironically, Jack Warner's beach house—of attorney Paul Ziffren and his wife, Mickey, have there been the proper social gatherings in town. In the seventies, Geffen spent some Sundays at the Ziffrens', where East Coast names such as Ribicoff and Kennedy would mix with Hollywood names such as Zanuck and Natalie Wood. In the arc of David Geffen's reinvention of himself, the Great Host role would seem the next natural phase. "Hmm..." says Geffen, pondering it. "I'd like to know the person who's going to do that, because I'd like to go to the party. But I don't think I want to throw the party. I don't have those kinds of social graces. I'm not a wonderful host. I'm a wonderful runner of a record company." What most Geffen intimates see are the same people in for afternoon barbecues Sunday after Sunday, very low-key, not unlike Edie and Lew Wasserman's barbecues in the fifties, where Janet Leigh would throw Tony Curtis in the pool and Lew would cook hot dogs.

It was raining the morning David Geffen took Irving Lazar through the Warner house on Angelo Drive. The tour had great significance for Geffen because of all of his friends perhaps only [producer] Ray Stark and Lazar had authentic memories of the place. As they got up to the second-story playroom, Lazar remembered a birthday party there, for Cole Porter. Judy Garland had sung Porter tunes at the piano. Lazar re-created for Geffen the whole party, down to the menu. That moment of recognition by Lazar must have been important to Geffen, for if he is in love with any myth at all, it's the colorful-mogul myth. Men like Jack Warner and David Selznick and Bill Paley and Sam Spiegel obsess him.

Geffen spends a lot of time talking about Spiegel, the late producer-bon vivant, who was a kind of role model. Spiegel's drive must appeal to Geffen, and also Spiegel's ability to collect people. "In Saint-Tropez, I would walk on Sam's yacht, and there would be Grace Kelly," Geffen says wistfully. "Or David Niven. Or von Karajan, the conductor." ("But Sam was a phony," insists Lazar. "If David compares himself to Sam, he was deluded by him. Sam was a hustler, and David isn't.") Still, Geffen is in awe of Spiegel's track record On the Waterfront, The African Queen, The Bridge on the Rmr Kwai, Lawrence of Arabia. "Sam made great movies," Geffen says. "Now, I think we've done good movies, but they are not The Bridge on the Rmr Kwai. I'm quite sure I'm never going to make movies as great as Sam Spiegel's movies. I hope one day I'll make even one that comes even close."

What seems to be on Geffen's mind a lot these days is aging. Not the literal kind (though there's that too), but the creative kind; the "being wrong" associated with the late careers of overachievers like Darryl Zanuck and David Merrick. "Sam taught me about that too," Geffen says. "There's a point at which you can't do it anymore. We all at some point or another are no longer contemporary." Will he know the moment? "I hope I'm smart enough to know the moment. I was smart enough to know it in the record business."

People are watching more closely than ever now that Geffen is Goliath and not just David. "We want heroes, and then we want to kill them," he explains. "We want to see that they have clay feet. I don't want to be a hero. I have clay feet. I'm imperfect in every way." So why are so many people waiting for Geffen to fail? "You know what? They'll succeed. I will fail. I have no doubt that I will fail. But I will also succeed."

And will he be the ultimate Hollywood Godfather, the role many people seem to want him to play? The man who can fix things, who can smooth things over. The man who can get people placed and replaced. The man whose phone call has the effect of a corporation.

He thinks that this is too dramatic a notion, that he's the fixer. "I don't have a Godfather capacity," he insists one afternoon in Los Angeles. "Explain it to me."

Call David. David can fix it.

"You're imagining that this is so," he says. "There are people who might call me and say, Gee, you know so-and-so. Do you think you might be of some assistance in this? And if I could be I would be. I make myself available to people to be of assistance to them. And, therefore, they are available to me to be of assistance to me. People help each other. I think that's appropriate."

Real success, Geffen suggests, comes from fixing yourself and not the squabbles of Hollywood. "On the day you die," he says abruptly, "you will be the only one who knows what lies you told. And how well, or badly, you behaved at any given moment. How brave you were. That's why you have to forgive people. Because each of us has to live with what we've done." You also have to forgive your own publicity, your own myth. You have to disregard it. As Geffen strode into a screening room at Warner's one afternoon, he pointed to a blown-up photo of Elizabeth Taylor caressing James Dean's head in Giant,

"These people are myths," he said. "People think I'm one of these people, but I'm not. I'm just a boy from Brooklyn who wishes he were six feet tall, with blond hair and blue eyes. That's who I really am."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now