Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

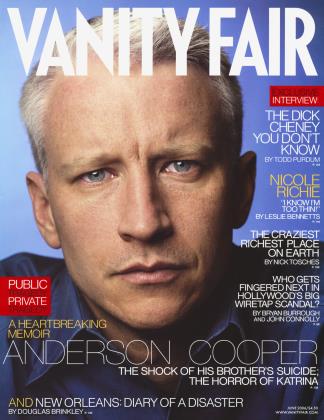

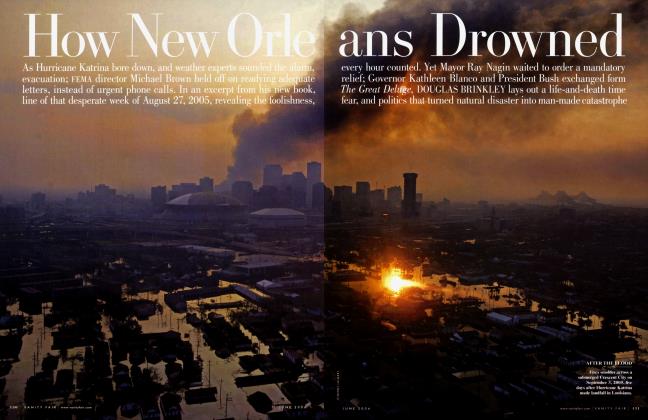

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWith his reports from the New Orleans disaster zone, ANDERSON COOPER became the conscience of a nation. But even as he shared the nightmare of a drowning city, another wall was coming down: the emotional one Cooper had built to shield himself from the memory of his brother's 1988 suicide. In an excerpt from his memoir, the now famous CNN anchor recalls how the epic tragedy he covered triggered a deeply personal reckoning

June 2006 Anderson Cooper Annie LeibovitzWith his reports from the New Orleans disaster zone, ANDERSON COOPER became the conscience of a nation. But even as he shared the nightmare of a drowning city, another wall was coming down: the emotional one Cooper had built to shield himself from the memory of his brother's 1988 suicide. In an excerpt from his memoir, the now famous CNN anchor recalls how the epic tragedy he covered triggered a deeply personal reckoning

June 2006 Anderson Cooper Annie Leibovitz View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now