Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPortraits, cityscapes, nudes, nature—for almost half a century, Lee Friedlander has brought his witty, skeptical, investigative eye to every aspect of the American scene, capturing the divide between expectation and reality. As the Museum of Modern Art opens what is perhaps its largest-ever one-man photography exhibition, VICKI GOLDBERG explores the quirky, unexpected power of Friedlander's perceptions

June 2005 Vicki GoldbergPortraits, cityscapes, nudes, nature—for almost half a century, Lee Friedlander has brought his witty, skeptical, investigative eye to every aspect of the American scene, capturing the divide between expectation and reality. As the Museum of Modern Art opens what is perhaps its largest-ever one-man photography exhibition, VICKI GOLDBERG explores the quirky, unexpected power of Friedlander's perceptions

June 2005 Vicki GoldbergIn close to 50 years as a photographer (not counting his first commission, at age 14, a portrait of the local madam's dog), 70year-old Lee Friedlander has been just about as influential, as prodigious, and as unpredictable as the weather. On June 5, the Museum of Modern Art in New York will open "Friedlander" with more than 500 photographs, probably MoMA's largest one-man photography exhibition ever (with yet more in the catalogue). Peter Galassi, chief curator of photography at MoMA and curator of the show, says, "I think it would be hard to come up with another photographer whose combination of quantity and quality has exceeded what Lee has done."

In the 1960s, Friedlander skittered across the metropolitan scene armed with ironic amusement and sly skepticism about the promise of America. What he called "the social landscape" was an urbanscape of mirrors, reflections, and obstacles, the multilayered, plate-glass city where new geometries emerge and clarity dissolves amid the manifold offerings of commerce. City people are incidental to traffic signs and streetlights, which are sometimes stand-up comics improvising at the crosswalk: one triangular sign valiantly supports a triple scoop of clouds, another stands en pointe atop a fake Egyptian pyramid. Friedlander has a gimlet, goofy eye for what were once called photographic mistakes: bumptious phone poles, stanchions, signposts, and window frames that obstruct, fracture, and confuse the view till it becomes a metaphor for the distracted consciousness of contemporary life.

In "New Documents," a 1967 exhibition of Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, and Friedlander, MoMA curator and photographer John Szarkowski wrote that a new generation of documentarians merely wanted to know the world rather than reform it—a cool, impersonal attitude akin to 1960s Pop and conceptualism. Even today Friedlander keeps his emotional distance, the better to describe the gap between the ideal planted by hope and convention in our minds and the stubborn nature of reality.

He takes his own portrait obsessively and obliquely, whether as a stalker's shadow on a woman's back or as a reflection in a store window, with a trophy for a head. Out West he photographed his shadow on scrubby ground where profligate bursts of weeds sprang from his head and crotch and lumpish stones seemed to replace his inner organs. His copious self-portraiture and intrusive shadow underline his constant investigation of the nature of our perception of the world in photographs, insisting that his images are pictures, in which the photographer is always, unavoidably present. His self stands in for our own; it superimposes its notions on our surroundings, tailors our perceptions to its measure, and yet is imperfectly visible to our eyes or understanding.

He favors formal complication, absurd viewpoints, inconsequential settings.

Though he consistently favors formal complication, absurd viewpoints, and inconsequential settings, Friedlander has consistently, possibly uniquely, reinvented himself with new subjects and slight shifts in style—respectful portraits of jazz greats, idiosyncratic snapshots of family and friends, nudes (including Madonna) in unheard-of poses, flowers, and more. A series of American monuments includes Mount Rushmore in reflection behind tourists studying it with binoculars, and a bronze World War I doughboy prepared to shoot a woman passing by with a baby carriage. The monuments are mostly lonely memorials that preside over gas stations, beached ships, and weeds, our marble reverence for the past outmaneuvered by the persistent bargain basement of the present.

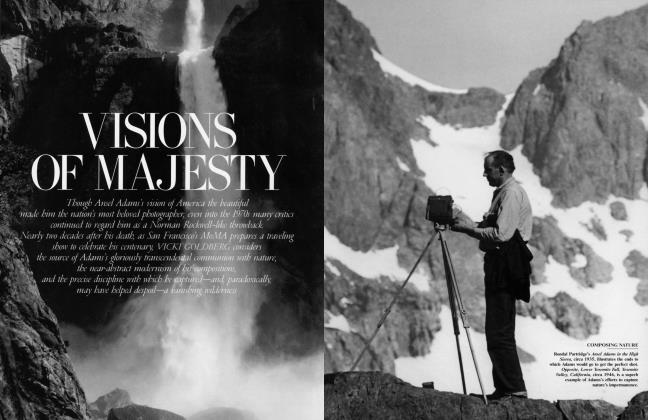

When Friedlander photographed television screens, some had eyes watching us, as if our representations could not be cowed. When he photographed factory and computer workers, labor looked as concentrated as hypnosis, with unintended consequences: two women poring over a thicket of wires became Siamese twins joined at the top of their hairdos. By the 1980s, he was discombobulating the landscape, especially in the West, as thoroughly as he had the city. Jeffrey Fraenkel of the Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco said Friedlander's pictures of Grand Teton National Park were "like Ansel Adams on crack." Others are full of delicate barricades: branches and leaves and underbrush that spatter and snake across the surface in patterns more clotted than Jackson Pollock's.

Friedlander's photographs are about ways of seeing and ways of being in a world where the built environment is as indifferent to us—and as messy and screwy—as the natural one. Who would have thought that America seen from such a wacky vantage point harbored its own order, humor, and hidden metaphors? No one but a photographer endowed with an elegantly complex formal instinct, a hip sense of irony, a maverick wit, and faith in the offbeat insights of his own spectacular curiosity.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now