Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

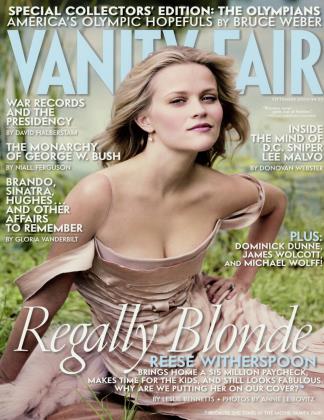

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWhile Legally Blonde earned Reese Witherspoon her $15-million-a-movie price tag and countless adoring fans, her dramatic test will be as a hard-to-love redhead: the scheming Becky Sharp in Mira Nair's adaptation of the Thackeray masterpiece Vanity Fair, opening this month. Unlike Becky, the 28-year-old mom likes to stay home and make dinner for the kids. LESLIE BENNETTS hears about the actress's movie-star marriage to Ryan Phillippe, her fight to be taken seriously—and her fear of cleavage

September 2004 Leslie BennettsWhile Legally Blonde earned Reese Witherspoon her $15-million-a-movie price tag and countless adoring fans, her dramatic test will be as a hard-to-love redhead: the scheming Becky Sharp in Mira Nair's adaptation of the Thackeray masterpiece Vanity Fair, opening this month. Unlike Becky, the 28-year-old mom likes to stay home and make dinner for the kids. LESLIE BENNETTS hears about the actress's movie-star marriage to Ryan Phillippe, her fight to be taken seriously—and her fear of cleavage

September 2004 Leslie Bennetts View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now