Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

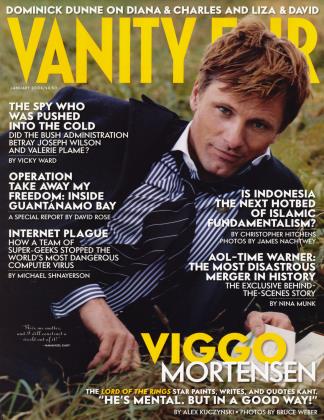

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowGiven Princess Diana's prediction of her own fate 10 months before she died, and how much her royal in-laws knew about the palace-rape tape she kept for protection, no wonder talk of conspiracy continues. While offering his own theory, the author remembers C. Z. Guest and reviews the Liza Minnelli-David Gest drama

January 2004 Dominick DunneGiven Princess Diana's prediction of her own fate 10 months before she died, and how much her royal in-laws knew about the palace-rape tape she kept for protection, no wonder talk of conspiracy continues. While offering his own theory, the author remembers C. Z. Guest and reviews the Liza Minnelli-David Gest drama

January 2004 Dominick Dunne View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now