Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCOVER STORY: THE FIRST 500

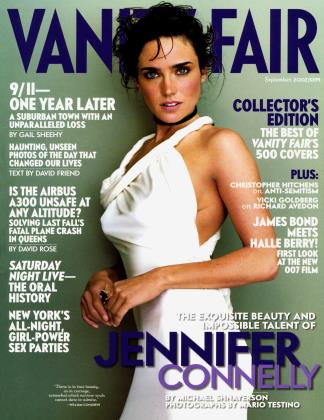

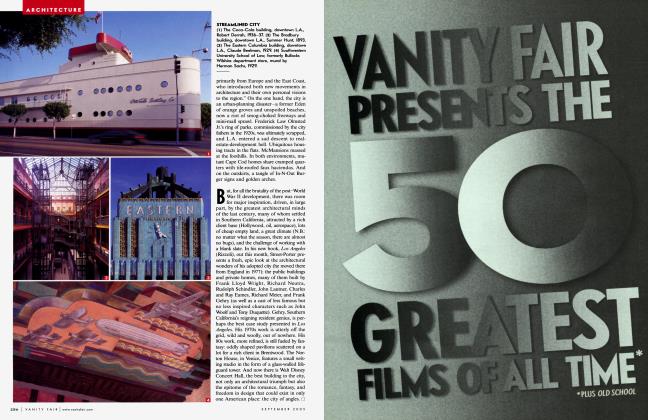

From the Jazz Age to the Depression, and from the go-go 1980s to the edgy start of the 21st century, Vanity Fair's covers have reflected the ideals and icons of their eras, inviting readers to the pleasures inside. As V.F. passes the 500-issue mark, here are some favorites among its elegant seductions

JAMES WOLCOTT

Magazine covers are mute observers of the present that recede into posters from the past. Like vintage posters, their faded pastels and antique details can tickle easy nostalgia. But the most beautiful, plush, superstylized covers of Fortune, The New Yorker, and Vanity Fair in their vigorous youth are more than souvenirs of a bygone age; they're emblems of ideals and aspirations that once animated a nation and a culture-signs of a dynamo optimism that would be dashed to bits by brute history. To track the covers of Vanity Fair in its first incarnation is to witness a country peeling off the genteel Victorian tradition petticoat layer by petticoat layer until it's lithe, frisky, and ready to dive into the champagne fizz of the Jazz Age. Founded in 1914 by Conde Nast and edited by Frank Crowninshield, a visionary genius disguised as an old-school gentleman, Vanity Fair took its name from the title of William Makepeace Thackeray's comic novel and its editorial spirit from the Shakespearean adage that all the world's a stage, its people merely players. The early covers are decked with Pierrots and Harlequins in diamond-patterned tights, diaphanous-gowned nymphs, and jewel-box lovers, tableaux reflecting a commedia dell'arte approach to the follies of the age. Some of these cover scenes had a gaslight glow. Others seemed illuminated by the bright lights of Broadway and the vaudeville circuit.

Visually, Vanity Fair was multicultural long before the word was manufactured. Fabulous illustrators such as Mexican-born Miguel Covarrubias, renowned for his portraits of Babe Ruth as pin-striped colossus and Greta Garbo drooping under the weary weight of her eyelashes, and Italian-born Paolo Garretto, who made Hitler's mustache an evil smudge; photographers such as Cecil Beaton, Horst, Baron de Meyer, Edward Steichen, Man Ray, and Nickolas Muray; and art director Dr. Mehemed Fehmy Agha introduced an energy, motion, theatrical brio, and courtly sophistication to American magazines, and elevated Vanity Fair into an elegant fun house for the best-dressed minds around. As the Great Depression deepened in the early 30s and Fascism reared its skull, the cover images took a more severe tilt, reflecting a world knocked off its axis. The "July 4" cover of 1933 shows Uncle Sam brooding like Rodin's thinker on the state of the planet, his head ceilinged by dark, troubling clouds. Inside, however, the contents of Vanity Fair played dumb to the psychological devastation of the Depression—it tried to whistle past the graveyard until prosperity returned—and this myopic denial, coupled with financial deterioration, lowered the curtain on the magazine in 1936. In the epilogue to the 1960 coffee-table anthology of Vanity Fair articles and pictures, I. S. V. Patcevitch, then president of Conde Nast, described the decision to fold the magazine as "heartbreaking" and wrote, "Ever since, for all the senior members of the Conde Nast publishing organizationincluding myself—the revival of Vanity Fair has remained an unrealized dream."

It took two more decades for the dream to be realized. In retrospect, the 80s proved the perfect opportunity. Ronald Reagan's morning in America was a rooster-crowing dawn of restored confidence and money creation. Only the long boom and conspicuous consumption of the Reagan era could fuel and sustain an expensive relaunch of a general-interest title in a magazine field that had splintered into a thousand niches. However, the lavish and glossy promotional buildup for Vanity Fair provoked inevitable grumbling from the peanut gallery, and by the time the first thick, keenly anticipated, all-star-contributors issue appeared, dated March 1983, journalists were juggling rocks in their hands, eager to converge like the villagers in Shirley Jackson's "The Lottery." The public stoning by the press nearly killed the reborn magazine in its cradle. Conforming to tradition, the first few issues of the new Vanity Fair featured illustrated covers. A rapid change of editors brought a change in cover policy, as Irving Penn portraits of authors and performers now loomed in dark, tight, all-pores close-ups. This, too, proved a stopgap. Italo Calvino may have been a wizard of a novelist, but a newsstand draw he wasn't. This profiles-inexcellence experiment was abandoned, and the magazine lurched through an identity crisis for its first (and, some thought, last) year of publication.

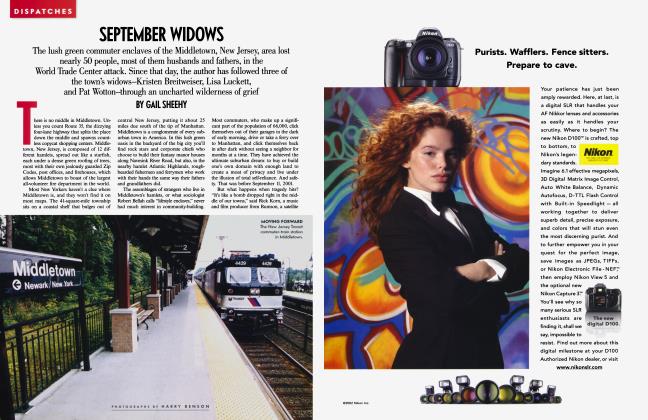

The cover of the April 1984 issue marks the true modern (postmodern?) christening of Vanity Fair reborn. Vanity Fair would be breathlessly contemporary but fulfill the mission and purpose of the original—to cover, in the words of Crowninshield, "the things people talk about... parties, the arts, sports, theatre, humor, and so forth." Some of the covers made news. Harry Benson's romantic capture of Ronald and Nancy Reagan holding each other as if preparing to whirl like Arthur Murray dancers was a controversial choice (the magazine was accused of pandering to the administration), but that was a minor fuss compared with the uproar two months later when a very different couple was showcased on the cover by the king of luxurious kink, Helmut Newton: Claus von Btilow (whose trial for the attempted murder of his wife, Sunny, would be retold in Reversal of Fortune) and his mistress Andrea Reynolds. Never had the name Vanity Fair seemed more apt. The 80s were a celebrity bonfire of the vanities, a muscle-beach orgy of exhibitionism.

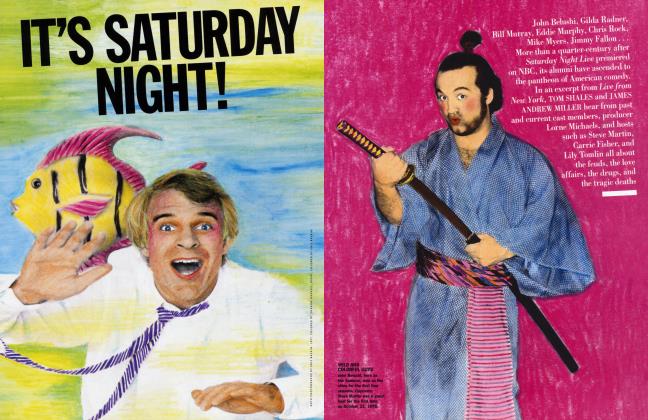

CONTINUED ON PAGE 311

Visually, Uinity Riir was multicultural long before the word was manufactured ... an elegant fun house for the best-dressed minds around.

Never had the name Vanity Fair seemed more apt. The 80s were a celebrity bonfire of the vanities, a musclebeach orgy of exhibitionism.

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 303

Since the Zeitgeist of decades often spills over the slotted time line (the "60s" truly began with the Beatles' arrival in America in 1964 and ended in the Watergate summer of 1973), the 80s were still going strong in 1991 when Vanity Fair published one of its most sensational cover coups, the Earth Mama portrait of a nude, proud, and pregnant Demi Moore (her stomach as big as a bushel) by Annie Leibovitz. Emanating almost more life force than a newsstand could contain, Leibovitz's nude madonna was praised, deplored, imitated, and widely parodied. It wasn't until the election of Bill Clinton in 1992 that the country seemed primed for a change of course, an attitude shift. Harvard and Yale would take precedence over Hollywood and Vine. Deficits (the morning-after hangover of Reaganomics) stretched to the distant horizon, and the jubilation over George Bush's Gulf War victory dwindled. It would be a time to retrench and reflect, and there were mutterings among media smarties that an 80s magazine such as Vanity Fair wouldn't be able to adapt. It would have to take profundity pills and swear off Dynasty shoulder pads, or end up rusting in the used-car lot along with other magazines overidentified with certain decades (such as Esquire with the 60s and New York with the 70s). Offering a nod to the consensus forecast for the 90s, Vanity Fair photographed Bill Clinton for the cover of the March 1993 issue in distinguished black and white. What innocents we were. His administration was soon tattooed in lurid tabloid colors and taken for a wild ride. For scandal, excess, and soap-opera drama, the 90s made the 80s look like a tune-up.

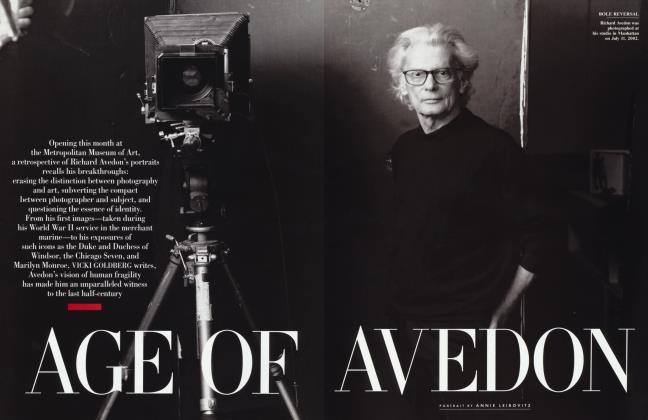

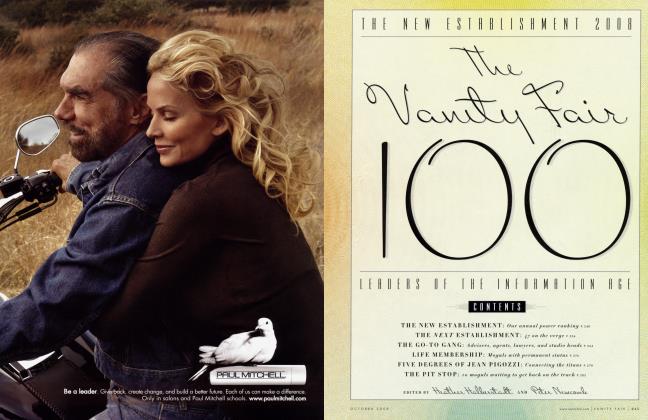

Nineteen ninety-two was also the year that Vanity Fair underwent its own change of administration, just in time for the show. Cover continuity was maintained—due in no small part to the phenomenal phone-juggling skills and tireless dedication of the indispensable features editor Jane Sarkin—but deepened, broadened, and finessed, or goosed with a goofy element of surprise (Jerry Seinfeld as Napoleon; Cindy Crawford lathering up k. d. lang in a bizarro gender-bender scenario). The magazine also infiltrated the executive suites of media and techno honchos, launching an annual search engine with the October 1994 issue to determine the pecking order of "The New Establishment." Taking the libidinal pulse of American business drove Vanity Fair in a new and defining direction, broadened its wingspan. The luscious work of Herb Ritts, Mario Testino, and Bruce Weber was complemented by covers that were more painterly than pop, as the color palette incorporated cool, minty blues, greens, and whites—a touch of frost. (Leibovitz's much-talked-about Gretchen Mol cover—the "nips" issue—holds up gorgeously as ice sculpture.) Weber provided a dreamy, elegiac remembrance of Carolyn Bessette, and Testino captured Princess Diana in her last, sunny bloom.

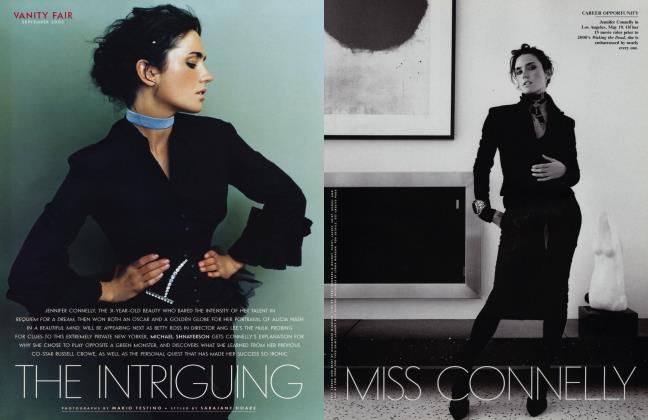

Perhaps the most painstakingly composed covers are the groundbreaking foldout editions done by Annie Leibovitz presenting group portraits of famous musicians, actors, the American Olympic athletes of the 1996 games, and politicians as if they were members of an 18th-century salon, an aristocracy of talent whose achievements intertwine. (The Bush II Cabinet took a break from the war on terrorism to get the foldout treatment in a special testosterone tnbute.) Leibovitz's music covers conjure up the "impossible interviews" of the original Vanity Fair, temporarily herding unlikely disparates such as Patti Smith, Dr. Dre, and Faith Hill into the same time-space bubble, with Macy Gray teleporting in from Alpha Centauri. The Hollywood covers, also by Leibovitz, are like an Oscar party come to still life, a mingling of Old Hollywood and New. The magazine has kept a beat ahead of the pack by playing talent scout and slapping on the cover newcomers who aren't bankable names—yet. Where some readers and commentators used to squawk about seeing the same old salamis, now they complain about staring at the cover trying to figure out who the hell this cutie grinning back at them is. This Heath Ledger, is it a person or a candy bar? But more often than not the magazine has been proven prescient in its rookie picks. Matt Damon, fresh out of the wrapper when he appeared on the December 1997 cover brushing his toothy teeth, has become a known commodity at the multiplex; Kate Hudson hasn't done too poorly for herself since October 2000; and the much-copied gatefold covers of the annual Hollywood issues roll out the showroom models of the talents most likely to succeed. The most prominent torso on the April 1996 Hollywood cover belonged to Leo DiCaprio—more than a full year before the release of Titanic.

The rotation of the stars isn't just a matter of refreshing the talent pool. It's putting new mass on the eternal cast of Vanity Fair, the comedy ensemble of fools, dreamers, coquettes, and knaves who act out the human drama on a bigger, sillier plane. When the original magazine began publication, the performing arts were the three-ring circus where vanity pranced for attention. The theater was pre-eminent, the movies a dim flicker. Movie stars dominate the covers of the second go-round of Vanity Fair not only because their good looks are enticing but also because Hollywood became and remains the international Valhalla of vanity, the pagan temple and world capital of mass illusion and myth. Not even TV and the Internet have been able to unseat it. Hollywood's faces are the most recognizable form of currency in our entertainment culture, trading cards that jump up and down in value, depending on the weekend's grosses. And our movie culture, to the discomfort of many, is the world's movie culture, which is why the covers of Vanity Fair's international editions carry the same pop that they do here. Tom Cruise and Julia Roberts translate universally. The cover of Time reigned for decades as the most telling and enshrining social indicator, but now that the newsmagazines peddle so many service-oriented bulletins—Shoes: Everyone's Wearing Them!— Vanity Fair monopolizes the mirror of our media existence. As with Frank Crowninshield's Vanity Fair, it is the sonar depth of the magazine's writing and reporting that keeps the faces of the pretty and powerful afloat in the pool of Narcissus. Covers seduce. The contents cinch the deal.

Hollywood became and remains the Valhalla of vanity, the pagan temple and world capital of mass illusion and myth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now