Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMcNAMARA'S SHADOW

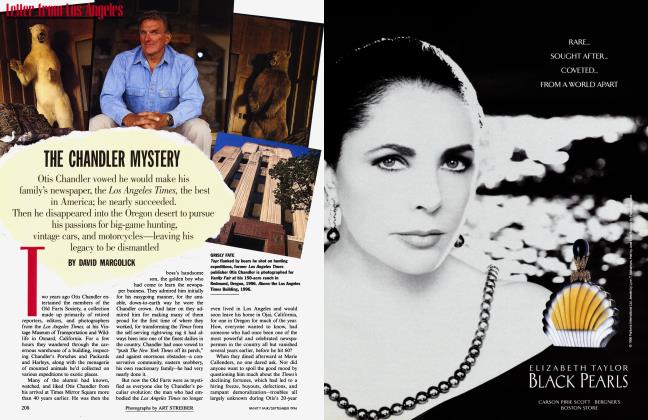

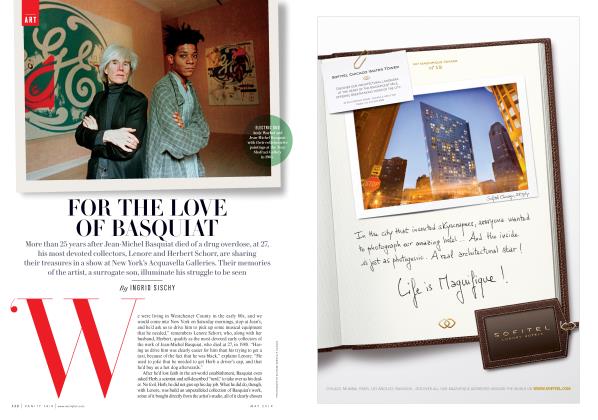

For 10 agonizing years, Paul Hendrickson struggled with his definitive study of Robert McNamara. The Living and the Dead, due out this month, reveals the full duplicity—and humanity—of the architect of Vietnam

DAVID HALBERSTAM

Many years after, you would spy him now and then on the street—a narrow figure in a tan trench coat hurrying down Connecticut Avenue or across Farragut Square or through the park that cuts in front of the White House. You would see him and start: My God, it's McNamara. The body was still lean and fit, remarkably so, but the face had now aged almost terrifyingly, as if meant to be a window on what lay heaped within. He was a ghost, a ghost of all that had passed and rolled on beneath his country in barely a generation.

—From the first page of Paul Hendrickson's The Living and the Dead.

Thirty-one years ago they seemed an unlikely pair to be pulled to a kind of mutual destiny, Bob and Paul. Bob was Robert McNamara, the secretary of defense and signature figure of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, the man to whom Johnson turned in all delicate issues of national security during the Vietnam War, not only because McNamara was so effective a spokesman and one who still carried the Kennedy imprimatur, but also because he was a man without doubts—at least in public. He was "the best man in this country," Johnson once told Turner Catledge of The New York Times. Paul was Paul Hendrickson, just emerging, at the age of 21, from Holy Trinity, a Catholic seminary in Alabama, where he had spent seven years studying to be a priest.

The date that Hendrickson left the seminary (he is very good at remembering dates, and after some 12 years of tracking Robert McNamara, he is also very good at matching the critical dates in his own life with those of America's involvement in the Vietnam War) was July 15, 1965—"that is, 13 days before Lyndon Johnson told the Big Lie, saying that the American force in Vietnam was going to go to 50,000 when in fact the decision had already been made to go to 175,000 men," he says. At the time, Hendrickson was both sick and in despair. He weighed only 135 pounds; as he later said, his bowels felt as if they were filled with razor blades, the result of too many years of following a path that was decidedly wrong for him. He made his way to St. Louis, where he quickly shed the accoutrements of his previous life, in particular his awful black mohair priest's suit, which he sold in a pawnshop for five dollars. "Can't pay you much—we don't have much call for preacher's suits," the pawnbroker said.

He had never been out on a date or even kissed a girl. "I was a world-class geek," he recalls, filled with self-doubt and an overwhelming sense of failure. He knew almost nothing of the profound social/cultural changes that were then rocking the country; they had barely penetrated the seminary, except for the great excitement on the night of John Kennedy's election, when Father Terrence assembled all the seminarians and told them, yes, the news was very good, the country had elected its first Catholic president. Hendrickson let his seminary haircut grow out. He tried to date, awkwardly at first. He would tell girls that he had gone to Staunton Military Academy, since he could not bring himself to tell the truth. He enrolled at St. Louis University, a Jesuit school, and went on to do graduate work in American literature at Penn State. Thinking he might become a writer, he stumbled into journalism, worked for a time in Indianapolis for the SerVass family on The Saturday Evening Post and at Holiday magazine before getting what he thought of as his first real job, as a reporter at the Detroit Free Press in 1972. It was a strong paper, and he found good mentors there. In 1974 he went to the National Observer, an excellent Dow Jones weekly, which never quite caught on. After it folded in 1977 he moved to The Washington Post's "Style" section.

To his surprise, he was good at journalism. Not only was he a good writer, but the seminary had bequeathed to him an intense intellectual discipline and other qualities that stood out in the profession. If most good reporters had a certain audaciousness and brashness, he was shy and private; he seemed to doubt himself at all times. But what distinguished him was his uncommon sensitivity, the ability to empathize, to identify with the people he wrote about. His stories had a certain texture to them: "It's like he's always not so much writing as he's always weaving, the texture is so good," says Mary Hadar, his editor at the "Style" section. "I fell for him from the start," said Ben Bradlee, then executive editor of the Post. "What he brings is not so much a newspaperman's sensibility to his stories but a novelist's sensibility. He's like a delicate flower that has to be watered more than the other plants in the newsroom. But he's a very good journalist too. The questions always get answered."

If Hendrickson shied away from stories that demanded he possess a tough and cocky exterior, he excelled at those that needed an unusual degree of subtlety and humanity. "His great strength—and I think it comes in part from the seminarian background—is his ability to empathize. He becomes in some way involved with the people he talks to, shares their pain," says Hadar. "And, fortunately for him as a journalist, he can back off just enough at the last moment and sense the feelings of the people his subjects may have affected in their lives."

"The deeper I went in, the more ties there were, and the bigger they were.... There was a totality of lying."

Robert McNamara, in those years, was still an icon, the man on whom no one in Washington laid a glove. The city might have turned on the Vietnam War, and would, a few years later, treat the Watergate conspirators harshly, but McNamara remained untouchable. A surprisingly deft and extremely ambitious operator, he at first basked in the reflected glory of the Kennedys; for a time, that protected him from the wrath directed at other architects of the Vietnam War. Then, as the Kennedy glow began to fade, he benefited from his friendship with the opinion-makers of Georgetown, particularly Katharine Graham, the publisher of the Post and an old friend from college days at Berkeley. Though he never spoke out on Vietnam, he would meet with the era's most senior journalists, in carefully controlled situations in which he would signal his doubts about the war, never, of course, speaking on the record. He frequently made television appearances, though the subject to be discussed was always agreed upon beforehand with his hosts—either overtly or covertly—and was always nuclear war, never Vietnam. He managed to become the least scrutinized major public figure of the modern era.

Ironically, it was one of those sanitized television appearances during which he spoke movingly about the terrors of nuclear war that connected him to Hendrickson. In the fall of 1983 both Hendrickson and Mary Hadar watched The Day After, a television movie about the horrors of nuclear war. Following the movie there was a panel consisting of, among others, Elie Wiesel, Carl Sagan, Henry Kissinger, and Robert McNamara. Hadar remembers seeing the panel and thinking, "McNamara—what a great story: a man who started out in this city with such great promise and then who has slipped into a kind of silent villainy. Maybe what we are seeing is a haunted man trying to get back something of his life." In her version, the first person she thought of for the assignment was Hendrickson, "because his great strength is empathy." Hendrickson remembers the idea as his own. He thought McNamara the most humane and humble of the participants. In the light of the struggle that would ensue between himself and McNamara, Henrickson now reflects, "I learned the hard way over the years that that face I saw that night was pure bullshit."

The day after the program, Hadar and Hendrickson talked. "I wonder if we can get him," Hadar said. He was, after all, the most elusive man in Washington, a figure of respect and probity, a member of the Post board. It was a bit of a reach for the edgy, irreverent "Style" section to approach him for an interview. Hadar thought there might even be trouble if they tried, and told Hendrickson she would talk to Ben Bradlee about it. But Bradlee was enthusiastic from the start. Hendrickson wrote McNamara immediately. Some five weeks passed and he got no answer, and then one morning, when he was sleeping a little late, he got a phone call at eight. "The voice at the other end sounded like a machine gun," he remembers. Hendrickson was skeptical enough to wonder whether the early hour of the call was an attempt to catch a journalist at a weak moment. McNamara said that he had no interest in being interviewed; he had a brutal travel schedule, which he thereupon outlined in detail to Hendrickson—meeting after meeting, airport after airport, each, it appeared, on a different continent, all, it seemed, for the betterment of mankind. Furthermore, he did not care about or read the "Style" section of the Post, and he did not want the piece done.

But somehow the letter had piqued his interest, coming as it did after the nuclear-war panel, and Hendrickson was invited to come by and see him a few days later in the late afternoon. That day they spoke about nuclear issues. Hendrickson had boned up on the subject, and he was an expert on how to talk to the Good McNamara, the one who was obsessed with preventing nuclear war. The V-word never came up. Why McNamara decided to see him, Hendrickson was never sure, in retrospect. Perhaps because McNamara felt protected at the Post. Perhaps because he did not read the "Style" section. Perhaps it was the ability of the ex-seminarian to exude innocence when he was not entirely innocent. Perhaps it was—and this was critical—the fact that Hendrickson had no history of being involved with or writing about Vietnam. There was one moment near the end of their first session when McNamara, referring to how many of his friends spoke of him as doing penance at the World Bank, said, "It makes me goddamn furious when people say I went to the World Bank to do penance for . . ." For a split second he hesitated, and Hendrickson thought he was going to say Vietnam, but then McNamara added, . . Defense."

Hendrickson began to undeigo nothing less than a second great crisis of faith in his life.

I think each of these two men in that moment believed he could manipulate the other: McNamara, the legendary control freak who always set ground rules for journalists, who still put the Vietnam section of his life off-limits (and who, after refusing to talk about Vietnam with me when I interviewed him for my book The Best and the Brightest, later told my friend Teddy White that the real problem with my book was that I had failed to ask him the right questions); and Hendrickson, who with his deft ability to read people saw that a window on the most secretive and conflicted of public men was now amazingly, albeit briefly, being opened to him. Whatever the reason, Hendrickson had passed his audition, and a series of sessions between the two men took place, spaced out over time, three or four or five weeks between meetings. Vietnam, Hendrickson thought, was everywhere and nowhere. It never came up, but the shadow of it was always there. ("Like Banquo's ghost on Macbeth's stage, it had seemed to hover just beyond the automatic click of the inner office door," Hendrickson later wrote.) Somewhere along the way there was the beginning of a relationship; the two seemed to like each other.

At a certain point during the interview process, Hendrickson's editors at the Post, including Ben Bradlee, mentioned to him that he should ask McNamara about a woman named Joan Braden. It is a testimony to how naive Hendrickson was and how removed he was from the high life of Georgetown society that he did not know at first whom they were talking about. For, at the time in Washington, the gossip was everywhere that McNamara, seemingly one of the great squares of the Western world, was having a passionate and rather public affair with Joan Braden, a prominent Washington socialite. She was the mother of eight, still married to and living with Tom Braden, a syndicated columnist. He apparently acquiesced in this arrangement, and they all seemed to travel openly together, if not as a threesome, then as a kind of tag team where Braden would be with his wife and then go off, to be replaced by McNamara.

The next time Hendrickson saw McNamara he asked about the situation. "Oh, that," McNamara said. He paused for a moment to consider. "I'm going to tell you two things—you write whatever you want to, whatever you have to. Just make damn sure you've got it right and that it's all factual." The second thing he said was that, as far as he was concerned, the less said about the relationship the better. A few days later he gave Hendrickson a phone number where the Bradens, who were traveling in Spain, could be reached. Hendrickson, thinking that he had come very far from the seminary, asked Tom Braden about the relationship between his wife and McNamara. "If it's balls, it's balls," Tom Braden said—a curious remark, which Hendrickson interpreted to mean: if they're doing it, they're doing it. Then Braden went back to drawing a bath and put his wife on the phone. Is it a romantic relationship? Hendrickson asked her. "Yes," she answered, "I will not say it isn't."

The resulting series of three articles, published in The Washington Post in May 1984, was, not surprisingly, a sensation. Hendrickson had come up with astonishing stuff; not only had he captured the emotional complexity of McNamara, a haunted man desperately on the run from himself and from the central issue of his career—Vietnam— but he had discussed the tastiest bit of Georgetown gossip of that season: the menage a trois. Predictably, Bradlee loved it. McNamara was less enthusiastic. He was in Europe with Joan Braden when the articles were published. He asked Hendrickson to send them by courier to him in Europe, and he read them on the way back. A few days later he spoke to Hendrickson: "Your courier service worked just fine," McNamara told him, "though I must say they are not the articles I would have written." Still, Hendrickson thought he had established a relationship with McNamara. By then he was receiving offers from publishers to write a book about him. In some complex way, he liked McNamara, empathized with his struggle against his divided self, and in his innocence he believed that he could write a book with McNamara's full cooperation.

Gradually, however, it became clear that the relationship was over. Access was withdrawn. McNamara said he was doing a book with another biographer and therefore could not be involved in a rival project. But Hendrickson decided to go ahead with the book anyway and signed a contract for $250,000 (as an advance against future royalties) with Summit Books. It was a huge amount of money for a young reporter who was then making about $45,000 a year. Unfortunately, Hendrickson quickly became a prisoner of the advance, believing that because the money was big the book too would have to be big. That meant he was miscast, trying to compete with such large-scale biographers as Bob Massie and Robert Caro, author of an epic biography of Lyndon Johnson. The Post articles were miniatures; their strength was a kind of journalistic version of cinema verite. Then there was the problem of losing McNamara's cooperation. "I think when he lost his access Paul felt he lost his book," Mary Hadar said later. Other reporters might lose access, she noted, and feel it was not so harmful to their books; indeed, they might even feel freer to pursue secondary sources. "But Paul works through personal connection," she explained, "and he really needs the heartbeat of his subject matter, the ability to work off a living person and to feel connected, and I think he felt lost without it."

The other thing that had begun to trouble him was that, as he started pursuing the McNamara of Vietnam (as opposed to the haunted McNamara fleeing Vietnam), he began to come upon the massive record of McNamara's deceptions, of public statements that systematically contrasted with private deeds. "The deeper I went in, the more lies there were, and the bigger they were, and I was completely unprepared for it. There was a totality of lying. It was devastating to me. I was finding out that the main subject of my book was a systematic liar. And I was unprepared for that—it was always important for me in some way or another to like the people whom I wrote about. So I would call my wife and say, 'Ceil, look at these lies, look at these lies.'" Other journalists—Seymour Hersh and Bob Woodward, to name two—might have had their appetites whetted in a case like this, but Hendrickson could not handle it. He kept a list of McNamara's lies, marked carefully on a sheet of paper, that contrasted what McNamara was saying publicly with what he was doing privately. The title he put over that chart is instructive: "Denying Man/Lying Man/ Stretching Man/Manipulating Man."

Hendrickson began to undergo nothing less than a second great crisis of faith in his life. The years 1985 and 1986 were terrible for him. "He would come upstairs from his office and you could feel the weight he brought with hiril, as if he were being pulled down not just as a writer but as a man," says his wife, Ceil. He consulted a psychiatrist, who told him to downscale the book in his mind; friends who were writers told him much the same thing. But he felt he owed something big because of the big advance. The book, he decided, was his own Vietnam. On leave from the Post, he worked on it from September 1984 to May 1987. By early 1987 he was broken both financially and emotionally. To his own mind he had accomplished nothing. His editor, Jim Silberman, remained encouraging, certain there was a book there. Finally, Hendrickson called Mary Hadar at the Post and asked if he could have his old job back. "Instantly," she said.

He wrote another, smaller book, about Marion Post Wolcott, a distinguished photographer of the 1930s, who along with Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans captured the grim mood of the country in the Depression. But unlike the other photographers, she simply stopped working at a certain point in her career. The parallel to his own life was all too obvious. "I was trying to answer an elemental question: If you give up something so basic to you, can you live out the rest of your life?" he says. The book received considerable praise and was nominated for a National Book Critics Circle award in biography.

At that point Jonathan Segal, the editor at Knopf who had worked on the book on Wolcott, called Hendrickson and asked him how he would do the McNamara book if he were to pick it up again. "Please, Jon," he answered, "don't even ask me about it." Well, suggested Segal, why don't you write me a letter? And so, over the next 72 hours, Hendrickson sat down and wrote a 45-page letter in which he said he would not try to write the definitive McNamara book but rather a book in which McNamara was the central character, a book in which his actions were shown to have had a profound impact on other people. McNamara would be the center of the wheel, and the spokes would go out from him to five other people. "You've found it," Segal told him, "and if you don't do it now it'll be terrible for you for the rest of your life. It'll haunt you forever." Knopf bought out the old Summit contract, and Hendrickson went back to work. He was, thought Segal, liberated, because he had found five people with whom he could empathize; he had found a human connection.

This time he knew the way. This time the form fitted his talent. Again he left the Post— this time from September 1993 to January 1996. The work flowed. His characters fascinated him: the young man who had tried to wrestle McNamara off the Martha's Vineyard ferry; the widow of Norman Morrison, the Quaker who had immolated himself in front of the Pentagon; James Farley, a Marine lance corporal whose face, as he wept at the news of the death of a comrade, had been immortalized in a Larry Burrows photo that originally ran in Life magazine; Marlene Vrooman Kramel, an American nurse in Vietnam, who looked back at her experiences there in unexpected ways; and finally Tran Tu Thanh, a middle-class, young Vietnamese, recruited by the Americans and then tragically abandoned by them.

In those same years that Paul Hendrickson had seen his original book slip away, Robert McNamara's reputation had steadily lost its gloss. Increasingly he seemed a relic from another age, a man who spoke out readily on all issues save the one he was supposed to speak out on. He was boxed in, impaled by the very myth he had so artfully created, first as one of the "Whiz Kids" at Ford Motor, and then at the Pentagon as the man who, because he had all the information, never made mistakes. The source of his power as a ferocious bureaucratic infighter had always been information—he had more correct information than anyone else, and that meant his was the greater truth, and therefore he was never wrong. But on the most important call of his life he had been wrong, and it was something he could not deal with. He had had his doubts about America's involvement in Vietnam as early as December 1965, but he had ended up remaining silent in public on a policy of which he was the principal architect, and which eventually tore the nation apart.

In 1996, Hendrickson finally finished the book. In terms of other writers whose books on Vietnam took over their lives, he gave himself the bronze medal for completing it in 10 years; Neil Sheehan won the gold for A Bright Shining Lie (16 years), and Bill Prochnau the silver for Once upon a Distant War (12 years). Though technically Hendrickson had taken 12 years from start to finish, he felt Prochnau deserved the silver because Prochnau had struggled without a break, whereas Hendrickson had gone back to the Post. Hendrickson's book, The Living and the Dead, published this month, is a remarkable literary and journalistic achievement, a stunning portrait of the most conflicted public man of our time. The McNamara whom Hendrickson depicts is bright, fierce, complicated, anxious to do good, but fatally flawed, his naked ambition to exercise power always overwhelming his other, more humane side.

McNamara was having a passionate and rather public affair with Joan Braden, a prominent Washington socialite.

Last .year, trying to come to terms with history, McNamara finally presented us with his own memoir, In Retrospect. It was a skillful rendering of the bureaucratic record, cobbled together in a way designed to minimize his own uniquely aggressive role as an advocate for intervention in Vietnam. In it he said that the architects were wrong, tragically wrong—not that anyone had much doubt about that by now. But it was an odd book, disengaged and cold, without a voice, almost completely devoid of feeling. In 400 pages, Hendrickson notes, McNamara wrote two sentences about his mother and father and declined to give their names. Above all, he never came to terms with his own role in the Vietnam period, as the hit man for the administration against any doubter or dissenter, the man who savaged anyone bearing information which might cast doubt upon the disastrous course they were all following.

McNamara's book sold well, as a curiosity, I think, the way Garbo's memoir might have sold: "McNamara Speaks." It is not a book that in any real way advanced our knowledge of the Vietnam period or brought any new dimension to a tormented figure from a particularly tragic era. It inspired rage on the part of many Vietnam veterans, as they realized for the first time that the man who had been so important a decision-maker had changed his mind about whether the war could be won and had remained silent while they and their friends continued to fight. McNamara, who went on tour to promote his book, seemed more than ever before a haunted man.

(Continued on page 251)

(Continued from page 244)

It is to Hendrickson's credit that in The Living and the Dead he does for McNamara what McNamara could not do for himself in his own sad little memoir: he bestows humanity upon him. In addition to everything else, Hendrickson tells an extraordinary story that seems to sum up the wrenching experience of McNamara's book tour. It is an incident that took place on the night of April 25, 1995, at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard. A Vietnam veteran named John Hurley got up to ask a question. He was at once very polite and angry; it seemed touch and go whether he would finish his sentences, so powerful was the emotion in his voice. McNamara's presence that night, he said, was an obscenity. Hurley began by noting that the reason for going into Vietnam in the beginning had seemed honorable and legitimate. He had no argument with that. But, he said, there was the fact that McNamara had clearly changed his mind very early on, perhaps as early as February 1966, about whether the war could be won. Then, his voice cracking, Hurley recited a list of the names of his comrades who had been killed in Vietnam after that date. "And you remained silent. You said nothing. You let 30 years pass." As he pushed on, Hurley was having more and more trouble speaking. The moderator urged him to ask his question. He listed the men again. "Why did they die, sir? Why did you remain silent?" That was the real question he was asking, not just for himself and for those men he had served with, but for the whole country. Suspense hung in the air as McNamara began to answer. "You're going to have to read the book to get the answer. There's not time . . ." he said. But Hurley tried to speak again, for he wanted not the book but this man himself to answer why he had stayed silent. "Sir, sir!" he said.

Now McNamara was beginning to blow. "Wait a minute," he said to Hurley, "shut up!" There was an audible gasp in the audience. Then the room fell silent, for this was the moment of truth, when Robert McNamara, so anguished and divided a man, would explain why he had not spoken out in those years. And then Robert McNamara gave the audience his version of the domino theory.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now