Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

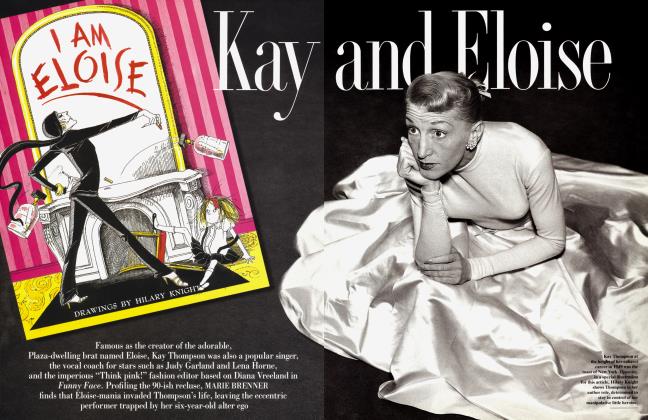

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHOOKED ON GLAMOUR

Letter from London

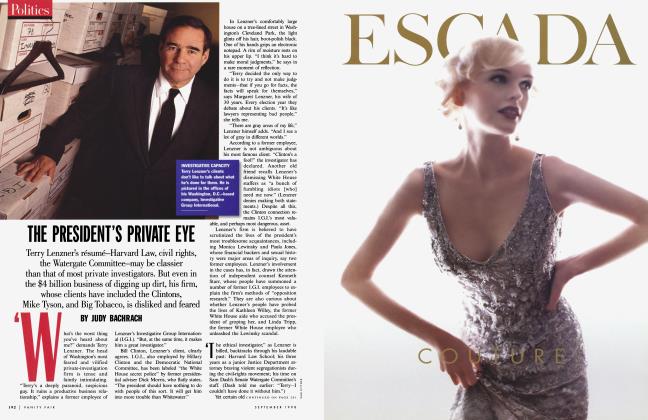

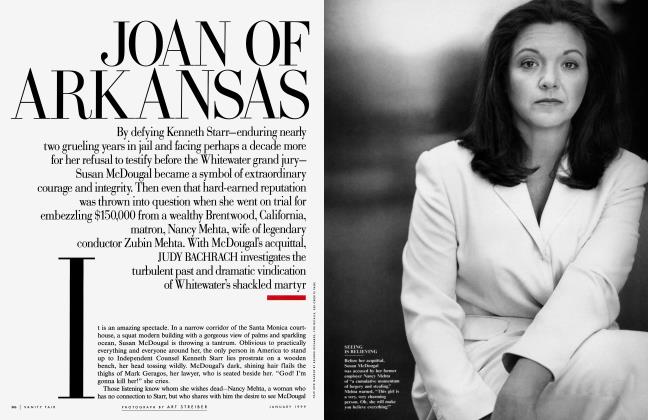

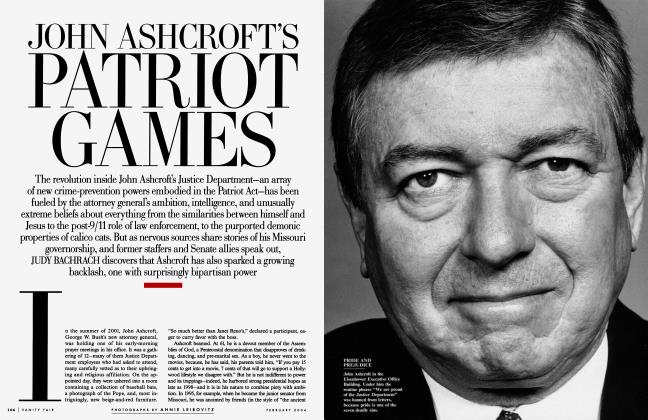

JUDY BACHRACH

The look of Swinging 60s London-Twiggy, Anita Pallenberg, Mick, and Marianne— sprang from Ossie Clark's fashion genius. But Clark's brilliance was eclipsed by a darker side, which led to his shocking murder in August

It is a dress quite unlike any other, a gray and cloudy affair, splashed with surprising twists of color: giant tulips plucked from barely cultivated groves, huge fleshy gladioli invading seams, sleeves, neckline.

A triumph of sinuous unpredictability, the garment has the inimitable trademarks of the artist: pure chiffon, cut on the bias, dances close to breasts, waist, and thighs, its color shifting quietly as the wearer moves. Beatrix Miller, former editor of British Vogue, understands the calculated impact of such a garment: "Heavenly," she calls it. "But not angelic."

Ossie Clark—certainly the most sensual designer to unfurl his talents from England's chilly shores—created this confection, with the help of his wife, fabric designer Celia Birtwell, in the late 60s, the era of which he became an absolute emblem. And cautionary tale. "I'm a master cutter," he declared a little less than a decade ago. "It's all in my brain and my fingers, and there's no one in the world to touch me."

The United States, dazed by trippy England during Ossie's short but glorious reign, craved what he made. On Seventh Avenue, lesser talents copied all his innovations—the devilish snakeskins; the romantic chiffons; the midis that swept away the minis; the famous flared riding coats; the soberly tailored men's jackets worn buttoned low by beautiful girls. So widespread were knockoffs of Ossie's designs that the Yankee consumer never really got to know the guiding genius behind the innovations.

Now it's too late: last August, Clark's life ended when he was stabbed multiple times in his council flat. Charged with murder is Ossie's lover, a once homeless drifter who had known the designer for 18 months, since the day Clark picked him up in Holland Park.

"I wasn't able to sleep at all," murmurs the great artist David Hockney, one of the high 60s' survivors. "Ossie died and that's one thing—but how he died: it took a while to sink in, really. . . . Dying on the floor ..." Ossie's friend and former lover shakes his head, willing the images away and the past. "He didn't know how to deal with his talent, really."

Like so many members of his generation, Ossie wasted all his assets. In the shredded fabric of the designer's extraordinary life you can see the strands of the 60s blowing slowly in glowing colors. Here are the rebellion, the fantasies played out in sexual abandon and brief explosions of urgent creativity, the drugs, the songs. And, inevitably, the burial. "I feel sorry for people who didn't see the 60s in London," says Celia Birtwell. "It was the music, it was the bringing down of all these stodgy rules, it was the freedom. I feel some people just couldn't take it. I feel Ossie was one of them."

Of her former husband she speaks with astonishing charity, considering the pain he inflicted. She talks of those he dazzled. Like Nicky Samuel, the London heiress and onetime girl of the minute (who later married jewelry designer Kenneth Jay Lane). Samuel recalls wearing that cloudy-gray gown with the tulips and "nothing underneath" for a Norman Parkinson shoot for Vogue. She had been feeling too woozy to pose, but relented. "Ossie did give one confidence," Nicky says, her smile wistful. "He adored my tits. He'd say, 'They're wonderful, darling.'"

Celia Birtwell understands how easy it was to fall for Ossie, even though the designer was not meant to find his ultimate sexual satisfaction with women. He had, she concedes, "wonderful taste in women . . . it's like a legacy in a way." By which Celia means the alliances with Bianca Jagger (for whom Ossie designed white silks and a delicious low-backed maternity dress in thick marocain); Julie Christie; Eartha Kitt (who requested snakeskin underpants to match her long skirt); Natalie Wood; and Bardot, of course. Brigitte loved everything Ossie. So did Patti Boyd, who continued modeling for Ossie even after she married George Harrison of the Beatles; Twiggy, who favored the designer's decadent frilled blouses; Anita Pallenberg, whose incense-scented house on Cheyne Walk became a hangout for Ossie and Hockney; and Marianne Faithfull, who turned Jagger on to the designer's sexy genius. For Mick, Clark created jumpsuits designed to unzip themselves onstage and a satanic black cape he wore at the Altamont concert where four people died.

"We made this incredible thing together. He was the toast of the town," says Celia, trying hard not to cry. "Ossie was the first person to make a show that was sort of like a happening. The Beatles were there—everyone."

Celia recalls an Ossie show at a club called, appropriately, Revolution. Jimi Hendrix was unmistakable, as was Patti Boyd "in a wonderful cream chiffon with powder-blue birds on it and an exquisite scarf." Birtwell, born a workingclass girl from the grim North Country which also sparked Ossie's rebellion, remembers feeling something bright burning inside her that night.

For Mick Jagger, Clark created jumpsuits designed to unzip themselves onstage.

"I mean, it was quite . . . ," she says, shaking her head. "Well, you did feel shivers down your spine." A pause. "I know what it was about really—the fusion of artistic talents. And it wouldn't have happened without either one of us."

It was an unforgettable and fragile era. Like Ossie, it didn't last long. "Yes," says Celia, with resignation, "by 1974, he really didn't want to do too much work—he thought he was such a success. He was getting bored, I think. He got bored terribly easily."

It is for this that Celia has never forgiven him: for the brevity of it all, for his lack of concentration, his inability to go on. "What a waste of talent, what a bloody waste of talent!" she cries with fury. "He could have been great."

She leafs through a book of sketches, which she has brought along in case, like so many, I do not remember the clothes. They are extraordinary, and as she turns the pages, it all comes back. I see a bared bosom brushed with voile, another peeping through crosshatches of silk, a naked back gleaming from a silvery tunic. And then, inexplicably, Celia's memory returns to the party, the night at Revolution. When it was all happening. "I was really proud actually to be there," she says. "I thought, They're my fabrics and they're these exquisite clothes. I felt really, you know, part of something great. I knew that. I know that. Hockney must have realized this was no ordinary talent."

David Hockney did, in fact, realize this, and not simply because Ossie took care to inform him how brilliant he was. Three days after my interview with Celia in London, I am sitting in the painter's home, high in the lush hills of Los Angeles. The house is alive with dueling colors: violent blue, mauve, tomato. In the living room a player piano fronts a mad fireplace framed by white trompe l'oeil columns on which painted dachshunds romp and sprint. In their midst, Hockney flashes a broad grin and recounts a snatch of old dialogue: " Well, ya know, I'm an artist, David The painter's blue eyes narrow with amusement as he recalls Ossie's hubris. "And I did say to him, 'Ossie, all the artists I know have one thing in common. They work all the time.'

"I'm sure he was an artist," the painter continues pointedly. "But artists are driven." Hockney—whom Ossie would blame for luring him away from Celia and then, later, after the two men had called it quits, for supplanting him in Celia's heart—recalls everything with mildness. He is an accomplished raconteur, despite his fading hearing. He cannot resist another memory. Before fame swept Ossie away, before Ossie swept Celia away, the young, brash designer spent many months living in Hockney's Notting Hill Gate flat. "I had this big room I slept in. And at the foot of this bed was a chest of drawers. And I painted in rather careful Roman letters: GET UP AND WORK IMMEDIATELY! So that was the first thing I saw each morning."

The artist drifts a minute, then continues. "So, it did work. Well, Ossie would have slept in that bed in 1964." Another pause. "But he was certainly attracted to glamour, a lot more than I."

In 1964, young Ossie was simply a beautiful man on the make, a talented scholarship kid at the Royal College of Art. Wildly flamboyant and as thin as a cigarette, he was in exile from England's downtrodden North and desperately seeking, as he always would, the glamorous life.

He was born Raymond Clark into a family of eight in Oswaldtwistle (hence the nickname), a small town on the Yorkshire border. His father was a seaman, often absent. His mother was busy—too many children and not much of anything else. "I was an incredibly difficult child, derided and jeered by everyone except my mother," Ossie would later recall.

The young man went to great pains to divest himself of his origins. "I had it taken away," Ossie replied to Hockney when, at their first meeting, the painter inquired what had become of his northern accent.

Bernard Nevill, a longtime textile designer for Liberty of London who was Ossie's college teacher and friend, made sure all his students wrote a treatise on some famous designer. "Ossie chose Lucien Lelong," he recalls. "I think the reason he chose him was not so much because he understood the style but because I told him Lelong married Princess Natalie Paley, a great model and a famous figure in 1935. It was the glamour. Because he had married a Russian princess. Ossie was hooked on glamour."

Back then Clark had the idea of glamour almost entirely to himself. It was still the era of pearls and English girls in twinsets. Debutantes looked exactly like their mums. Swinging London was an oxymoron. "If you went into the City wearing anything other than a white shirt," reports designer Michael Fish, "you'd be sacked."

"I had a stand-up row with Maggie Buchanan, who was then fashion editor of Harper's Bazaar, because I put green and blue clothes together; she said, 'You just don't do that!'''''' So recalls Chelita Secunda, who left the magazine world to work as Ossie's public-relations woman. (To celebrate, she dyed her hair metallic blue.) "We did a picture of a girl and a guy getting out of bed; it was an underwear ad. They wouldn't print it because she wasn't wearing a ring.

"I mean, that's how it was."

Then the music changed. The scene shifted. "Suddenly working-class became the most fashionable thing ever," recalls Celia. "Suddenly," recalls Hockney, "being provincial kind of gives you an edge." Suddenly Carnaby Street was hiking short skirts to breathtaking heights and Jagger was licking his large, insouciant lips.

"Somebody told me afterwards: 'We always loved your dresses, Ossie, because you could just open the skirt and fuck the girls.' That's true!" This the designer himself would remember with considerable pride. He did, after all, invent the wraparound skirt. "We followed this feeling of freedom that women got."

"It's hard to explain the effect of what that social breakthrough was," says Michael Fish, a refugee from the hallowed Turnbull & Asser, who, glimpsing the future, dressed Jagger in frocks and sold shirts pink as blush to aristocrats and average stockbrokers. "We were the blue-eyed boys in London, fashion-wise. We were very bold and outrageous." The Peacock Revolution, it was called. Fish, who preceded Ossie (along with Mary Quant, of miniskirt fame), rallied the troops. "Suddenly it was all right," he says, smiling faintly. "The correct people decided it was all right: you could just wear a pink shirt. Or a lavender shirt. Suddenly Jimi Hendrix said, 'Purple is the color of the universe.' "

Into this exhilarating milieu Ossie Clark, fresh from college, and equipped with his school's very highest marks, plunged. He was fired by images from The Women, the bitchy film based on the Clare Boothe Luce play, which Nevill had shown the class: "Real prewar flamboyant stylish," Ossie would later sum up, "that inspired me to make clothes that were sexy, and where women were like women."

He was by no means the only cocky young grad intending to leave his mark: Zandra Rhodes would emerge, hot on his heels. But Ossie came better prepared than most. Much to his initial annoyance (because, as Bernard Nevill explains, "everything was Youth and Young and ' We don't want to look at all these old-fashioned things/' ") he had been dragged by his professor every Wednesday afternoon to the Victoria and Albert Museum. There he had examined exquisite clothes from the past: splendid 30s silks seductively cut on the bias by Madeleine Vionnet (she would influence Ossie to the end), classics by Schiaparelli and Molyneux.

In 1965, Clark joined up with Alice Pollock, a young designer who had formerly been Orson Welles's assistant. With an instinct for the moment that never deserted her, she opened a shop called Quorum in a prim white house on Radnor Walk, off the King's Road. "Alice was wild, completely wild. She had big ideas," says Celia. Ossie was her biggest and certainly her wildest. No more dull, boxy miniskirts. No more women who were simply, as he later put it, "tall, glamorous things that swayed at you." He savored the revolution and launched the ultimate rebellion—new ideas that drew both romance and insurgency from the past.

"He wasn't just driven by the forces of modernity," explains Marit Allen, who as a Vogue editor was the first to fall for Clark's clothes. "Those short trapeze shapes of Mary Quant's simply didn't interest him. In those days it was quite revolutionary to go back to the 30s and 40s."

But Ossie didn't lead his revolution alone. By his side was his live-in girlfriend, Celia, whose lush marocains and extraordinary prints heightened the crafty and dramatic cut of the garments.

"We started a weird affair; it was sort of in the mind. We shared the same bed," she explains with unusual candor, knowing full well that half of London speculated for years about the true nature of her relationship with Ossie Clark.

"Whatever people say—you know, 'She married a gay guy.' " Celia shrugs. "I feel that's very unfair. There was nothing really unusual about—how can I say this?— our situation. Because the thing of this work began to emerge."

In 1964, Celia's new lover vacationed in America with David Hockney. They took in the Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl. And there were other diversions. "Well, I did have a little scene with Ossie," Hockney says. "Actually, he bullied me into it: 'C'mon, David, c'mon/' For somebody who was sort of nelly, Ossie was certainly aggressive sexually."

It was the music, it was the bringing down of all these stodgy rules. Some people just couldn't take it. I feel Ossie was one of them."

But back in London, Clark thought better of the affair. "He rang and said he missed me," recalls Celia. "Would I forgive him? Well, forgive him because he wanted to wash up with Hockney." She thinks a bit. "And I weakened. And I let him."

How on earth, Celia wonders to this day, could she possibly have denied him? "You know, he was a very, very persuasive character, a very strong character. All I know is he felt he should be with me. And I was of two minds. . . . But he loved me, and I grew to love him."

It is easy to see why. Celia's unlined face, Hockney has observed, resembles portraits of Rembrandt's young wife, Saskia. Like her predecessor, she proved to be her husband's greatest inspiration— as she herself understands. Celia shows me her sketches filled with Ossie's notations, exclamations, protestations. "I believe the only great time for us was '66 to '74. I mean, the talent, the art, this amazing thing that was brewing!"

'People have tended to forget about the bosom. I think there's going to be a lot of it around this summer," an earnest Ossie informed reporters in 1971 at the height of his fame, just as his newest line—designed for the first and last time in Paris—was about to be launched at Chelsea's Royal Court Theatre. He was the first to choose dramatic settings and wild rock as the backdrops for his sweeping creations: he favored anything flared out, the dresses spread like fans. "Ankle-length, beautiful skirts," recalls Nevill. "In Paris they'd hung them for 10 days to get the hems dropped; that's why they were wonderful."

Mick Jagger couldn't stay away from Ossie shows. Bianca considers him, after all the greats she has known, "one of the most talented designers I ever met." The shoe king Manolo Blahnik recalls "flamingo legs with hot pants. So beautiful! God!" Hockney came often with Peter Schlesinger, whom he would paint most famously staring into a shimmering blue swimming pool. On one occasion, the two dressed in matching white suits and Schlesinger looked, according to Nevill, "like the boy in Death in Venice." Also in evidence: a beaming Lord Harlech, whose pretty daughter, Alice, was modeling, and Cecil Beaton, whom Ossie wished, more than anything, to emulate. Everyone.

"Oh God! Terence Stamp has fallen ma-a-dly in love with you!" Ossie gushed one memorable night to his favorite model, Kari-Ann. Like Ossie, she was out to conquer. One night, she remembers, after she got a bit high and "danced this seductive little dance," the Hollies turned her into a hit song, changing only the spelling of her name. "Hey, Carrie-Anne / What's your game now / Can anybody play?"

Ossie's clothes, like his models, were the rage of London. Unlike many of his rivals, he worshiped the female form; his efforts emphasized rather than concealed.

"No knickers," Ossie warned his public. "The lines would show." "Ossie—he made it seem quite all right and acceptable," Patti Boyd says. (She is divorced now from both Harrison and her second husband, Eric Clapton.) Though she was convent-educated she embraced Ossie's clothes and the metamorphosis they inspired. "I felt he designed for us; I mean me and the friends I had at the time."

"Why are you so depressed?" asked the P.R. woman. "I got married yesterday/' Ossie replied.

The little shop itself was full of the most gorgeous garments and people—and the most indescribable chaos. David Gilmour, later to become lead guitarist of Pink Floyd, drove the Quorum van; upstairs there was a modeling agency called English Boy, which employed the handsome sons and daughters of the upper classes—Sir Mark Palmer; Julian Ormsby-Gore, son of Lord Harlech; Lady Carina Fitzalan Howard, now married to David Frost.

In another apartment lived Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones, who would eventually drown in his pool after a day of drugs and drinking ("death by misadventure," read the coroner's report). "Every now and then Brian would emerge and phone—he'd moved into the Ritz or something—and he'd order a load of shirts, like he was ordering from the laundry, because Ossie also made men's shirts," reports Chelita Secunda, who worked in that era at Quorum.

Downstairs was anarchic and insane. The clothes were so much in demand they could barely be kept in stock. The Beatles dropped by, as did Britt Ekland, the sometime actress who would marry Peter Sellers. A boyfriend of co-owner Alice Pollock at one point put a washbasin in the back "and set up as sort of a mini-hairdresser—it became a hangout place," Secunda recalls brightly. "I mean, since nobody was working nine to five it didn't matter if you wasted the odd hour here or there."

But Ossie, in that remarkably fecund period, worked feverishly, at times. "He took amphetamines," Celia says flatly. That, she says, is how the miracle of his collections was invariably produced. "He would make 20 fantastic garments, staying up all night; he would just produce at the very last minute this extraordinary collection."

All the old rules evaporated. "Ossie used to love coming here to the house. He'd bring boyfriends," says Nevill, referring to his own Chelsea house, piled high with Persian rugs, skins of bear and sheep. "With boys—oh yes!—he was always falling in love."

In 1971, Ossie went unaccountably missing from his shop. Chelita Secunda, boarding a plane for a vacation in Trinidad, was astonished when she found the missing toast of London in the seat next to hers. Ossie's face was buried deep in his hands and he looked, she says, "glum-glum-glumglum."

"Why are you so depressed?" asked the P.R. woman. "What's going on?" "I got married yesterday," Ossie replied. "What do you think you're doing coming on holiday with me?"

Ossie said simply, "Celia's pregnant." He would honeymoon solo for more than two weeks, while his bride stayed at home. This would become the pattern for their marriage, which might not have taken place had it not been for pressure exerted by David Hockney.

"I do know that when Celia became pregnant it was Hockney who ordered him to marry her," says Zandra Rhodes,

Hockney says, "Well, I kicked in. She was pregnant and wanted the child. I said to him, 'Well, you could do a lot worse. She's a terrific bird.' But I know he wasn't very happy when they married."

"Because, you know," Zandra Rhodes declares with perfect accuracy, "it was always Hockney that adored Celia."

For years a very deft painting by Hockney hung in the Tate Gallery in London. Entitled Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy—Percy being the cat—it draws its dignity and endearing formality from Gainsborough, but relies for its true inspiration on the artist's deep and even passionate understanding of the couple, who posed for him in their balconied apartment on London's Linden Gardens.

Ossie, in a blue sweater and bellbottoms, gazes directly out of the picture, his expression at once sullen and somehow fearful. In her long velvet robe, Celia, who would be the painter's model in more than 70 works throughout the coming years, is infinitely more beautiful and composed. A pale, imperious hand is thrown on her hip.

"Celia rather likes posing and dressing up," says Hockney. "I'm happy to draw her. I mean, I felt strong feelings toward her and it was expressed in the drawings really. Well, first of all, she looked beautiful."

Hockney pauses. "And, of course, Celia is standing." By which he means: Celia is always in control. Even when she had her two young sons, Albert and George, and not much else to sustain her. Certainly not a husband.

"He could become quite violent at times," the painter recalls of his old friend Ossie. "I was there sometimes. I just said to him, 'Don't hit Celia in front of the children. They'll remember.'" Hockney's voice descends to a whisper. "That's all I would say."

Were amphetamines the reason for the violence?

"Well, it could be. He was always on speed."

And, as ever, glamour was his other drug, equally addictive. There was the trek to Marrakech when Ossie stayed with Talitha Getty, who would die some years later of a drug overdose. There was the time in the South of France when Ossie arrived with an armload of quacking white ducks for director Tony Richardson, whose house was in the hills above Saint-Tropez. "I don't think Tony ever forgave us," reports Secunda, who accompanied her boss on that French jaunt. "You see, we put these three ducks in Tony's swimming pool—the same pool painted by Hockney with Peter Schlesinger standing at the edge. And it had been a clean swimming pool, you see . . . "

Secunda pauses. "I tell you, there were all these signs of madness at the time." Among them were Clark's business practices. "Just take it, darling," he commanded hordes of special friends, who were thrilled to obey his wishes. Anita Pallenberg received a snakeskin coat and a flowing chiffon morning gown in a purpleand-gray print by Celia. She wasn't the only beneficiary of Ossie's largesse.

By 1975, two events had upended the designer's dreams: Celia, at the end of her rope, left him for another man, an illustrator. And Quorum, the hippest place in London, mired in bad business deals, quarrels among the partners, egos, shoplifting, drugs, and arrogance, closed.

It was to Celia's side that Hockney quickly rallied. He bought her a glorious diamond ring (the newspapers instantly valued it at $40,000), which still graces her right hand. She began to join him in his Paris flat on the Boulevard Saint-Germain, where he sketched her endlessly: "It's not just one face," he marvels in his studio. "I never had to struggle for her likeness."

"I just looked at that Boy and saw those eyes. I said to Ossie, 'Would you please be careful, darling.' "

Hockney became, in essence, godfather to Ossie's two sons and the mainstay of Celia: protecting her, loving her, escorting her about town to Philippe de Rothschild's house or Nevill's. He began talking in a paternal fashion to the boys—often about their father, who was becoming increasingly incomprehensible to them. "I would tell them he was eccentric," he says gently. It was Hockney who flew Celia and the young children to California on many a vacation; it was he who lent Celia a packet of money, which allowed her to open her own fabric shop in 1983—the very year in which Ossie was forced to declare bankruptcy, as it happened.

London's most exceptional designer became divested of literally all his prizes—his store, the artist who loved him, and the wife who inspired him. "He was very, very attached to Celia and in love with her," Bianca Jagger insists.

"Ossie seemed to want to blame Hockney, you see," explains casting agent Ulla Larson, the designer's closest friend in his waning days. "He came between them, you see. That's Ossie's version. He was very jealous."

"See, because of the boys I had to take Celia's side," says Hockney. "I mean, I never had an affair with Celia," adds the man whose exploits as a gay libertine have been often documented.

But you did love her?

"Oh yeah, oh yeah."

Twelve years ago the once dazzling designer summed up the pathetic trajectory of his life after Celia. He was in bankruptcy court, dressed at the time in a scruffy overcoat. Tears flooded his eyes. "I have not been able to work properly since we were divorced in 1975. Our parting sent me completely to pieces. I fell into a deep depression and I have never recovered."

The loss of Celia had embittered and hardened him. He had lived, after the marital split, in Hockney's flat. It is said, in fact, that Hockney returned to England once to discover his locks changed and his old friend leaning out the window, screaming, "Squatter's rights! Squatter's rights!"

"See, he felt Hockney owed him," says Secunda.

In his last years, Ossie was on the dole; he was arrested for drugs, for assaulting a police officer; he borrowed money from all his friends. George Harrison lent him £15,000, which the former Beatle never saw again. A plea for £20,000 was faxed from Ossie to Mick Jagger, who never replied. In Ossie's dreams, however, the glamorous life still sparkled, like images in a flashback. He had a million plans. He wanted to open another shop and he was obsessively keeping a diary. "Quite bitchy really," reports Celia, who keeps the black notebooks, which London's upper crust is aching to bum, in a bank vault. (The portion I saw records the detailed utterances of all participants and an astonishing range of sexual activity.) When Christian Lacroix informed the International Herald Tribune's Suzy Menkes (who gave a dinner in his honor two years ago) that he wished above all to meet the renowned Ossie Clark, the latter arrived in her London house in open-toed sandals with his dog Pippin and told the assembled company that he was penning a blockbuster tel 1-all. He'd gone from brilliant to burnt-out, from adored to ignored.

"I mean, he had a touch of madness," says Hockney.

The new insanity may have been his most effective shield. Around the time Quorum had closed in the mid-70s, Clark's dearest friends had begun using other designers. "He didn't make my wedding dress, Yves made that," explains Nicky Samuel. "Well, one had moved on a little bit. I had a different set of friends: Maxime de la Falaise, Andy Warhol ..."

I'm afraid nothing can help now. I'm beyond repair," Ossie told Denise Golding about a decade ago. Golding now runs a Buddhist group out of her beautiful white Georgian house in Chelsea. When Ossie first became involved with the group, Golding promised him a change, if he persevered, if he kept chanting.

The aging designer was beginning to feel overwhelmed by guilt. He'd been, as his friend Jenny Dearden says, "a hopeless father"—of little use in the upbringing of his sons, whom he loved in a tender, if ineffectual, way. At the end of his life, says Celia, it was the sons who helped support their father.

Ossie could become quite violent at times," Hockney recalls. "I just said to him, 'Don't hit Celia in front of the children.' "

There were few others willing to give him money. His newer friends were of a different class. In his last months, Ossie was living with Diego Cogolato, a 28-year-old former heroin addict from Italy, whom he had picked up in Holland Park. "Ossie's son knew Diego and thought he was terrible," says Hockney.

But then, no one liked Diego. Eventually, even Ossie kicked him out of his flat. However, on the night of August 6, around nine P.M., according to neighbors, Ossie relented. The next morning, Ossie's body was discovered. Diego would later tell Ulla Larson, who visited him in jail, that he'd heard voices in Holland Park: Satan spoke to him, he said, and there were other voices, too.

Larson told the young man how very distraught Ossie's sons were. "Let them come and kill me," Diego said.

Now in Wormwood Scrubs prison, charged with murder and sheathed in plastic garments so he can't attempt suicide, Diego is referred to by Ossie's few remaining friends as "the Boy." The Boy, they say, helped himself to wine at their houses, without asking. The Boy was sullen, brutish, handsome, greedy, by turns placating and offensive. The Boy and the designer drank hugely, fought harshly. In the last months of his life, Ossie cracked a plate over the Boy's head, and the police were called.

"He appeared to me as were a spoilt boy," says Patti Boyd, her lips stiffening with outrage. "The first time I went, the flat was in immaculate condition with a beautiful vase of flowers, a little Buddhist shrine." Ossie was happily listening to his favorite country-music station on the radio, whipping up a red cocktail dress for his former model. He still worked from time to time on an old sewing machine: the results were impressive, but no longer brilliant. "He'd sort of ruin the rib cages," Celia reports.

Ulla Larson warned Ossie Clark against Diego. "The Boy wanted to commit suicide," she says. Nonetheless, she invited them both to her flat. "They were arguing and arguing. Quite frankly, he wasn't very well brought up, that Boy."

The Boy accompanied Ossie to some of his Buddhist meetings, which, with their Japanese chants and ritual simplicity, must have puzzled him exceedingly. (According to those who met him, the Boy was "narrowly educated.") In any case, he persevered. One day, not long ago, Jenny Dearden awoke to hear what she first thought was an auctioneer in her garden. On closer inspection, however, she discovered an uninvited Ossie and his friend, chanting. On even closer inspection she found a denuded refrigerator. "He and Diego had helped themselves to lots of good things, and lots of yogurts. I don't think anyone realized how hungry he was, you see."

Hungry for everything, it seems. "The second time I went out to dinner with Ossie and the Boy—the second time," says Ulla Larson, "they had a fracas. I just looked at that Boy and saw those eyes. Saw that kind of anger and I said to Ossie, 'Would you please be careful, darling.'"

"Is he very important, darling? He seems so primitive," Lady Henrietta Rous, a London gossip columnist, asked Ossie of his friend.

"Yes, Henri—that's what I like. The butcher, the peasant."

bumped into Ossie on the street about a year ago," Lord Snowdon says, "and he said he wanted a copy of a photograph I'd done of him in The Sunday Times." The photographer shows me blowup of a reclining young man, wearing a pink-and-brown shirt dotted with palms, and snub-toed boots. Lying across from him is Alice Pollock in a blue gown opened to reveal her pretty chest. It 1970, summertime. The two look smooth and petulant, as though it were in their power to make everything as it had been. Brilliant, youthful, daring.

"Sometimes," Celia says with gentle gravity, "the light goes out."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now