Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOH, SUSANNA

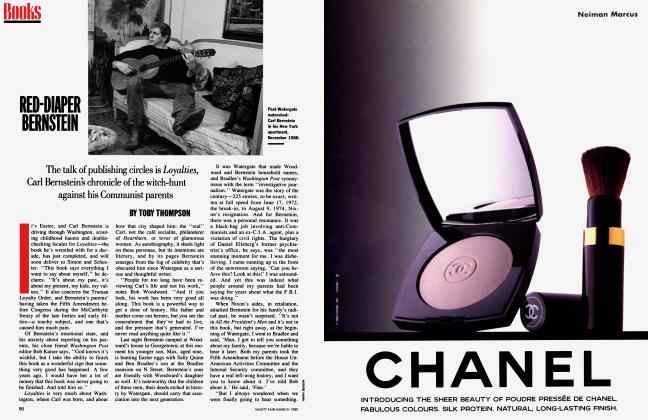

Books

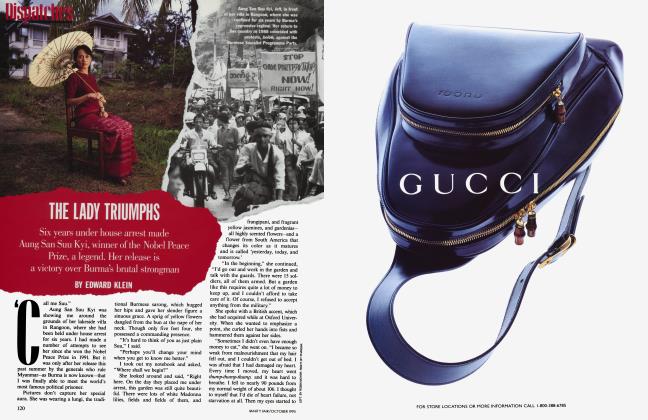

In Honolulu, Hollywood, and Washington Square, Susanna Moore found inspiration for her sharply elegant novels; her latest, In the Cut, is an erotic thriller that hits frighteningly close to the bone

GEORGE HODGMAN

FOR DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

When I tell Susanna Moore that a woman I know gave up on her new novel, In the Cut, after 30 pages because of the raw sexuality, she is joyous, happy to shock. "That's precisely the kind of woman who should read the whole thing," Moore says in her little-girl voice, adjusting the Cartier watch on her left wrist. Circling her right wrist is a tattoo bracelet: blue triangles like small, jagged teeth. Moore, who gained attention with her acclaimed first novel, My Old Sweetheart, is as elegant as her wristwatch. And as sharp as her tattoo. Small ironies, eccentric details—the fact that in her old hometown of Honolulu they still use the word "spaghetti" for pasta—produce wry smiles. She is highly literary, a woman who says her life was changed by her first reading of Forever Amber at nine years old and who speaks in the cadences of The New York Review of Books. But she looks like the model she can barely acknowledge once being, and on her tape deck there are works by the Cranberries, Sonny Boy Williams, and Snoop Doggy Dogg. Moore is equal parts Hawaii—where she was raised—and Hollywood, where she found herself in the 60s, playing one of the 10 slave girls in the Dean Martin movie The Ambushers. She had been hired by the costume designer Oleg Cassini. "I was the only one who could speak English," she teases jokingly. "And I was the only one who wasn't fucking Oleg." She stops herself, looks a little abashed, then shrugs. "I guess this is not the time to suddenly get ladylike."

Not exactly. In the Cut, which Knopf will publish in November in numbers (100,000 copies) designed to generate best-sellerdom, may make her the notorious woman you sense she has always dreamed of becoming. She could play it. There's a low-key, sophisticated theatricality about her. "I realized that from the time I was very, very young I was both spurred on and excited by the idea of my own disobedience," she says. "I've been drawn on, seduced, and aroused by that idea my whole life." She lingers briefly, contemplating the notion of her arousal. It seems to please her.

Outside her windows, the boom boxes in Washington Square Park are pumping in the August heat. "Murder weather," she intones as she rises to make martinis, using tiny airplane bottles of Finlandia vodka, the brand recommended by her friend Bill Blass. The bottles themselves, acquired during the research for Moore's novel, are gifts from policemen friends, met during the writing of the book, who are dating stewardesses. She emits a sharp giggle at the word "dating." Like the heroine of In the Cut, a linguist who obsesses over subway talk ("He just want to conversate and I just want to blowse through my magazine"), the fittingness of malaprops ("very close veins"), and the color of street language (we learn, for example, "freezerator" for refrigerator, "knockin' boots" for sexual intercourse, "gangsters" for breasts), Moore is absorbed by turns of phrase. And by worlds not usually embraced by ladies with Cartier wristwatches.

"Growing up in Hawaii, I saw very quickly that there were two worlds," she says. "There was a white world of power, prestige, and gentility, and then there was a much larger world of the Polynesian, Japanese, and Chinese. It was clear, if you were paying attention, that everything interesting was going on there. Language, sex, food, music, magic. And I was intrigued by it, beguiled by it. I wanted it." She read voraciously, but mispronounced words constantly "because

I had never actually heard them spoken." The world opened with the discoveries of Allen Ginsberg's Howl and Antonio Carlos Jobim's first album of bossa nova. "It was the one with 'The Girl from Ipanema,' " she says. "I remember sitting in the cane fields, listening to that album on an old phonograph that was on the veranda. I was so greedy for the world. And so desirous."

At 17, she left Hawaii for New York, looking for her own adventures, armed only with "four or five letters of introduction to rather grand people. And alligator shoes." Lonely and homesick, she spent her evenings listening to Hawaiian music at the Waikai Club on Broadway. "It was all xylophone," she recalls, "but it was close enough." After a first job at Bergdorf Goodman, she modeled without ambition and married without success before finding herself cast in the aforementioned Dean Martin movie by the aforementioned Cassini. Yet she had no desire to act—at least not on-screen—and she went to work as a script reader for Warren Beatty ("Casting's down the hall, baby," an onlooker yelled the day she arrived for her interview), who later used her in a scene in Shampoo. Next she went to work in Jack Nicholson's office, again evaluating scripts. It was California, the late 60s. "Very beautiful," she says. "You know, the dusty orange light. It's sexy. I kept thinking that whoever came here first, whether it was the Spaniards or Cecil B. DeMille, must have thought it was paradise. But it was extremely provincial. There were wonderful bookstores, but the only place you could buy clothes was I. Magnin." She married production designer Richard Sylbert (Dick Tracy, The Cotton Club, and Reds) and had a daughter (now 20). They traveled from location to location, and souvenirs from those years (she and Sylbert split in the late 70s; she can't remember quite when) pop up around her apartment—and float between the lines of her books. Among these are a pair of jade Chinese hairpins, which are significant in the new novel.

In the Cut began as a detective story. Sick of herself, Hawaii, and "the adorable young women" who had been the protagonists of her books The Whiteness of Bones and Sleeping Beauties, Moore immersed herself in the novels of Maigret and Simenon and fired off a letter to the New York City Police Department, more specifically to the commissioner for public affairs. (The title, predictably, made her laugh.) She asked for permission to "go around" with some policemen. "I was going to see what I could get. I said, 'I want to be in the car.' So I got sent up to East Harlem, to the Manhattan North Homicide Squad, which was good luck, because they're sort of the hotshots. I was assigned to these two guys who I could see were not happy to be stuck with me. It turned out they were quite serious homicide detectives. And then something interesting happened. It was as if I were holding up a mirror and they were looking at themselves for the first time, and they thought, Yeah, O.K., interesting. They were drawn in. They were seduced by this reflection of themselves that I revealed to them as I asked them questions about their lives. And so they kept me on. You know, what should have ended in two days became two weeks. Then two months. Then two years. Off and on. I think they were rather thrilled to disabuse me of my innocence."

"I'm not interested in dispassionate appraisal," says Susanna Moore. "I'm interested in passion."

She saw crimes, punishments, and autopsies, and made friends on the force. And she has produced a remarkable novel that is erotic, intelligent, and daring. Reminiscent of Diane Johnson's The Shadow Knows, narratively unflagging, and violent enough to bring down the wrath of feminists and senators seeking photo ops, In the Cut is destined to be discussed. Moore has created a woman whose courage never asks you to stand back and admire it, a woman beyond romantic expectations, polemics, all conventional comforts. Coolly intellectual and unapologetically sexual, Francie lives in an apartment on Washington Square Park and navigates her world alone, without complaint. She has defined her own unique satisfactions. When the killing begins, she makes a martini, buys a new book, and just keeps going, keenly aware that everything is possible. Moore is proud of her creation, but is both wary and sanguine about the fact that many readers and critics will compare her life with her heroine's. "Fiction reveals the writer," says Moore. "Autobiography is mirrors and tricks. And lies. I'm not interested in dispassionate appraisal. I'm interested in passion." And then she tries to articulate the qualities of the woman she has brought to life. "She has no one to fall back on," Moore says quietly. "She's full of melancholy and loneliness and bravery."

When I ask her if she finds the solitary requirements of a writer's job a difficult thing, she makes a different point. "You're always watching, if you're a writer," she says, "and I think it makes it harder for the person you're with. Your watchfulness can be exhausting. You know, that's the point where the person says to you, 'Look. It doesn't mean anything. It just is. Why does everything have to mean something?' My daughter once said to me, 'Mother, you're a little too interested in everything.'"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now