Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

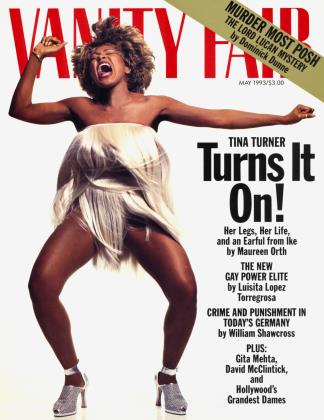

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFEAR AND HATRED IN THE NEW GERMANY

The casually brutal death of a young foreigner, whose neo-Nazi killers may yet go free, reflects the ugly and troubling forces rumbling within Europe's mightiest power

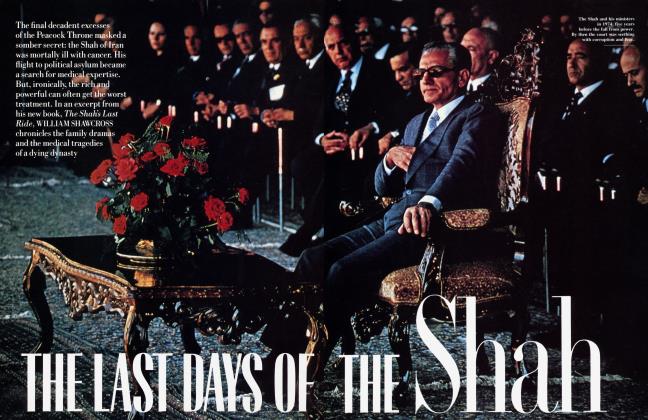

WILLIAM SHAWCROSS

nisnatrhps

On the night of November 24, 1990, in the small town of Eberswalde in eastern Germany, Amadeu Antonio Kiowa, a slaughterhouse worker from Angola, was beaten into a coma by a group of drunken thugs shouting neo-Nazi slogans. The police stood by, literally, as Kiowa was attacked, doing nothing to help him. He never regained consciousness.

An appeals court will soon hear the case of three German youths convicted in Kiowa's killing, which has become a symbol of growing racial tension and the rise of neo-Nazis in Germany. There is a good chance that the original verdict will be overturned—in which event the murder of the 28-year-old Angolan will be one that never happened.

Kiowa's was not an isolated case. Last year, violence against foreigners reached epidemic proportions in Germany, on both sides of the former Iron Curtain. Indeed, one can say that in the reunited Germany foreigners are the new Jews to the neo-Nazis.

After Kiowa's death, his German girlfriend gave birth to a son, whom she named Amadeu. She was subjected to abuse and harassment. Neo-Nazis in Eberswalde daubed swastikas on the baby's pram and even set it alight.

Exactly 60 years after Hitler came to power Germany's federal government has warned for the first time that rightwing terrorism poses a greater threat to the state than that from the left. The

Verfassungsschutz, or secret service, says there are now about 41,400 rightwing extremists in 77 different parties, gangs, and groups.

According to government figures, in 1992 there were 4,587 xenophobic atI tacks; these included 538 arson attacks and 18 bomb attacks on foreigners. Seventeen people were killed. In October 1992 alone, 740 incidents were registered. These included 82 arson attacks, three bomb attacks, 66 attacks against individuals, and 589 other criminal offenses such as robI bery, threats, and slander.

Many of those attacked are asylum seekers or refugees. Most of those arrested are juveniles or young men. The majority are skinheads or devotees of heavy-metal music. They often call themselves neo-Nazis, and brandish the emblems and slogans of the Fascist regime.

The wave of violence is one of the prices being paid—by foreigners— for the blithe, almost careless way in which the two German states were propelled into reunification in October 1990, just a year after the Wall came tumbling down.

German politicians, especially Chan® cellor Helmut Kohl, assumed that the West German "miracle" could easily be applied to the East, and that within a couple of years the country would be successfully integrated.

Despite the euphoria of that time, there were those who spoke against hasty reunification. One of the Jeremiahs was Gunter Grass. He warned that, after Auschwitz, Germans "have every reason to fear ourselves as a unit." He was derided and abused.

Now Grass feels that he has been vindicated. ''It's coming out as I predicted," he told The New York Times. Far from being a matter of joy, reunification has caused the specter of Nazism to rise once more in the heart of Europe.

I n central Berlin nearly all traces of the ■ Wall have been removed—too much I so, perhaps, for now Checkpoint Charlie is little more than a nondescript kiosk. Nonetheless, to travel from former West Germany to former East Germany is still to cross a great divide.

The West carries the imprint of 48 years of democratic restraint, increasing prosperity, and bourgeois satisfaction, if not complacency. The East still bears the scars of the brutal dictatorships which it suffered for 60 years.

Reunification was originally meant to be a shared burden.

But almost all the pain of it has been borne in the bankrupt East. Former chancellor Willy Brandt once said of the two Germanys, "What belongs together will grow together. ' ' But that has not yet happened. In the East, people often speak of arrogant ' ' Wessis" with fear and loathing; in the West, the idle, scrounging "Ossis" are mocked. The concrete wall is gone, but "die Mauer im Kopf"—the wall in the head—remains.

From Berlin, I drove north and east to Eberswalde. The town where Amadeu Kiowa died is in the Land, or state, of Brandenburg, which, in terms of rightwing attacks, is the second-most-violent state in Germany.

I took small roads, which twisted close to the Polish border, through rather desolate terrain. Small brown and gray bungalows and poorly designed industrial parks, many now abandoned, were patched onto the farmland and in between the beech and pine woods.

In the 17th and 18th centuries this area of flat farmland provided a haven for persecuted Huguenots from France; there are still many French names in the telephone book. Poles too were usually welcome here. In the early 20th century, steel and chemical industries were established in Eberswalde, and in the Second World War it became a key armaments center. En route to Berlin the Russians captured the town, and then it was bombed by the Luftwaffe itself.

After the war Eberswalde became one of the most important Soviet garrisons in East Germany. As late as the 1970s some streets and areas were reserved for the exclusive use of Russians. Today it still has the largest Russian base in the country; there are some 20,000 troops stationed just outside the town, with their own airport. They are due to return home this year.

In Eberswalde, one of my first stops was a welfare office catering to foreigners. It had for sale handicrafts and knickknacks from various parts of the Third World. Under the Communist regime, blue-collar jobs were done by foreign workers, under contract with their governments. The Eberswalde crane factory employed mostly Cubans; the Angolans, like Kiowa, worked in the slaughterhouse.

When the police finally approached Kiowa's fallen body, one of the skinheads said, "This black is only sleeping."

The foreigners lived in hostels and had little contact with ordinary Germans. Quite apart from their color, they were resented for the fact that they could sometimes travel to the West and were often able to obtain dollars and shop in the hardcurrency stores. The chief of police of Eberswalde reportedly claimed on one occasion that problems arose because of different behavior patterns: Africans were more emotional than Germans, he said.

In 1989, there were about 191,000 foreigners in East Germany, most of them contract workers from Vietnam, Poland, Mozambique, the Soviet Union, and Hungary. Since the Wall came down, the majority of the contract workers have returned home—only to be replaced by a tide of refugees.

F rom the center of Eberswalde I went ⅜ to see the place where Kiowa had I been murdered and, later, to look for his girlfriend, Gabriela Schimansky.

The road out of town runs through a seedy industrial area which contains the large, ugly, red brick chemical works. Behind them are some of the workers' apartments, built in the 60s and 70s by the Communist regime. These are depressing structures, though no worse than many other housing projects built in the same era in both Eastern and Western Europe.

Almost opposite the chemical works, on the main road, is a small working-class pub called the Hiittengasthof. This place is deserted at lunchtime, but in the evening it livens up as workers come in from the chemical factory on their way home. On weekends it sometimes has live music. Unlike certain other bars, it made a business out of catering to foreign workers, in particular the Africans, who were not always made to feel at ease elsewhere.

"There aren't so many of them now," said the middle-aged waitress. "They've either been sent home or they've gone to the West, mostly." While she spoke, the bartender chased schnapps with beer and smoked furiously, stabbing his cigarette onto the zinc counter. "It's very terrible what happened," the waitress added. "Germans should be ashamed. The Angolan turned the wrong way outside. If he had gone the other way he would still be alive."

Farther out of town, off the same dingy road, is another place of entertainment: the Rockbahnhof. It too looks like a very ordinary pub. On a wall outside are scrawled, in English, the slogans FUCK THE POLICE and FUCK THE SYSTEM. The customers of the Rockbahnhof are almost all working-class kids from the nearby housing project. Some of them are skinheads. Some—not all—would call themselves neo-Nazis. Some carry baseball bats, the accessory of choice for young, violent Germans. They listen to blaring heavy-metal neo-Nazi music, which they often greet with shouts of "Sieg heil" and "Heil Hitler." They tend to get hog-whimpering drunk.

On the night of November 24, 1990, the manager of the Rockbahnhof became alarmed by the behavior of his young clients, which was more than usually drunken and aggressive. He called the police and informed them that there was trouble brewing.

A group of about 50 of the thugs left the bar, swinging their baseball bats and shouting abuse about blacks. They rampaged down the road and past the chemical factory toward the Hiittengasthof. They shouted "Germany for the Germans" and damaged a few cars and a snack shop. Horst Schulz, the owner of the Hiittengasthof, was warned of their approach by the police, and decided to close early.

Among the patrons of the Hiittengasthof pushed into the street were Amadeu Kiowa, his cousin Francisco Dos Santos, and a friend from Mozambique, Armando Meque. Before they could make it back into the relative safety of the town itself, they were spotted outside the chemical factory by the mob from the Rockbahnhof.

Kiowa and his friends were set upon by at least 15 of the drunken thugs, some of whom were wearing masks. Many more stood about, jeering and cheering. Armando Meque was badly knifed. Francisco Dos Santos was beaten savagely with baseball bats. Kiowa was knocked to the ground and repeatedly kicked and beaten and stamped on by the young Germans. One of the defendants later testified at the trial that a skinhead in a hat said, " 'He is still breathing,' and jumped with both feet on the head of the Negro. ' '

Three police officers, armed but in plain clothes, were standing nearby, outside the chemical factory. Astonishingly, they watched the attack but did nothing. "I called my colleagues back because I didn't want any trouble," one of them later said. They also claimed they had been waiting for reinforcements. But nearby, behind the Hiittengasthof, sat another 20 policemen in their cars. They sat there throughout the incident.

When the police finally did walk up to Kiowa's fallen body, one of the skinheads who was still standing around said, "This black is only sleeping." Amadeu Kiowa never came out of that sleep. He died on December 16, 1990. His son was bom just a few weeks later.

Aim lights, dry-ice smoke, shaved■ I headed musicians, violent heavy-metIr al music. The music is integral to the neo-Nazis. Their most popular band is Storkraft (Destructive Force), based in Dusseldorf. Its 1990 song "Kraft fur Deutschland" (" Strength for Germany ' ') has lead singer Jorg Petrisch shouting,

We fight shaved, our fists are hard as

steel,

Our heart beats true for our fatherland. Whatever may happen, we will never leave

you,

We will stand true for our Germany, Because we are the strength for Germany, That makes Germany clean.

Germany awake!

At the end of some concerts, the audiences begin chanting Nazi slogans, or giving Fascist salutes, or even unfurling swastika flags. Such Oi music—neoNazi rock—is becoming more popular, not only in Germany but also in other parts of Central Europe.

In East Germany, extreme-right sympathies began to develop among the young in the early 1980s, in part as a rebellion against the Communist regime. Kids started to dress as skinheads and to favor heavy-metal music; they made isolated attacks on foreigners and homosexuals. But the constitution of the German Democratic Republic had outlawed Fascism. So, if and when these people were brought to trial, they were called hooligans, and thus depoliticized. In 1988 the Movement of 30 January, named in honor of the day Hitler became chancellor, was founded in East Germany. In 1990 another neo-Nazi group, the National Alternative, was created.

In the West, the most important extreme-right group has long been the Republican Party, led by Franz Schonhuber, a former member of the Waffen SS. Today it is the respectable, formal face of the German right, analogous to Jean-Marie Le Pen's movement in France. Its members do not wear brown shirts or flourish swastikas. Their slogan is "Deutschland den Deutschen"—Germany for the Germans. People with such sympathies tend to speak of the former East Germany as "Mitteldeutschland," implying that the lands to the east, now Poland, which were ceded after World War II, are still part of the real Germany.

For years the West German secret service excluded the Republicans from its annual report on extremist groups. So the Republicans could claim that they were democrats. Now they are listed, and claim they are being persecuted. In January 1989, Republicans were elected first to West Berlin's local government and then to the European Parliament and to the state parliament of Baden-Wiirttemberg. As yet, they have no seats in the federal parliament. But since reunification their support has been growing.

In Eberswalde, I went to see the local Republican Party leader, Jorg-Dieter Vennen. Vennen is the landlord of a poor working-class pub, Richterplatz. At lunchtime a few men were drinking beer; on the wall a Republican Party poster declared, WE ARE RADICAL AGAINST THE DESTRUCTION OF YOUR INNER SECURITY. On another wall was a tatty poster of Alice Cooper with a python wrapped around his neck.

There was one word which came up again and again in conversations in Eberswalde and elsewhere in the East. "Frustration." About 20 percent of the work force in Eberswalde is thought to be unemployed. The town used to depend on its crane works and the chemical factory. The crane works have been closed. The chemical factory and others are barely running, with far smaller work forces than ever before. Things seem to be getting worse.

Vennen, a man with wispy hair and an earring, took a classic populist or even Poujadiste position. He claimed that the Republicans "stand for workers and small people. We would have saved the crane factory here. We would build houses and make the streets safe. We want the police to have more rights, though not a police state. The courts should give tougher sentences. We need more money spent on youth work."

After Gaby and Amadeu started dating, they were harassed in the streets. "Sometimes we were threatened with knives."

Reunification had brought such expectations, and such disappointment. And, now, such insecurity. ''Before, we were organized, or in prison—we couldn't worry. Now we do," said one woman.

The principal effect of reunification, in the former German Democratic Republic, has been unemployment. What was called the "necessary shrinking" of East German industry has now become virtual deindustrialization and is having terrible effects upon the entire economy. Since 1989 the number of those employed in eastern Germany's manufacturing industries has fallen from three million to an estimated 700,000. As unemployment has grown, so has intolerance toward foreigners, especially refugees.

Germany has probably the most liberal refugee policy in the world. In effect, the constitution mandates that anyone arriving at a border who seeks asylum be allowed to stay, pending a hearing. At a time when much of Europe has been in disarray—if not, like Bosnia, in a state of horror—it has been inevitable that Germany would seem to millions of people the safest and most easily navigable haven. It takes about half of all the refugees given asylum in Europe—far, far more than any other country. There are now some 1.4 million refugees in Germany. Among the largest groups are Iranians, Afghans, Romanians, and citizens of one part or another of the former Yugoslavia. Last year about 500,000 arrived.

There is no country in the world which could cope easily with such an influx, particularly at a time of social and political upheaval and economic crisis. According to government figures, the cost to the German state of housing and keeping asylum seekers is around six billion marks ($3.6 billion) a year. They have become hapless scapegoats for the nation's traumas, and the government has often failed to protect them. Nothing shows this more brutally than the death of Amadeu Kiowa.

| madeu Kiowa Jr., now aged two, II and his mother, "Gaby" Schimanrtsky, live in a decrepit apartment building on a side street where houses still bear bullet holes from World War II. On the pavement, a drunk lay

bleeding from where he had banged his face as he fell to the ground. Passersby were solicitous and someone called an ambulance. "He's always drunk," said one man.

Gaby is a thin, wiry, and taut woman with a frizz of dark hair. She was bom in the town of Schwedt, a few miles closer to Poland. Her parents, now both dead, were workers in the chemical and crane factories. She came, in other words, from the poorest of the East German working class.

She met Amadeu in 1987. He had come to East Germany on a contract between the Communist regime of the G.D.R. and the government of Angola; he was living in a hostel for foreign workers and sending back almost 30 percent of his salary to the Angolan government.

The state prosecutor said his investigation of the murder ran into "a wall of silence, ignorance, secret agreements, and cover-up."

Gaby said there were three buildings at the hostel in Eberswalde: Poles lived in the blue block, Angolans in the red block, and Mozambicans in the brown block. She thought there were about 250 other Angolans working with Kiowa in the slaughterhouse. About 15 of them had German girlfriends.

She said she did not know much about Kiowa's life before she met him, or about his family back in Angola. After she and Amadeu started dating, they were harassed in the streets. "Sometimes we were threatened with knives. It happened constantly when we were out together."

Things got worse after the Wall came down—perhaps because people were less cowed by the police and felt freer to express their prejudices, but also because the new federal government insisted on sending asylum seekers to the East, against the advice of human-rights and refugee groups. Tensions between East Germans and the foreign contract workers were already high. When tens of thousands of refugees were also assigned to eastern German towns, tension became violence.

The night of the attack, Gaby was

waiting for Amadeu. When he did not return home, she went to the hostel; a Mozambican man told her that something had happened at the Huttengasthof. At the hospital she was told that Amadeu was in the coma from which he never emerged.

After her baby was bom she was taunted and abused in public. "Skins sprayed swastikas on the pram. One night my neighbor's flat was wrecked. I think they thought it was mine. I knew them. They were newly shaved kids from next door."

She moved for a time to Berlin in the hope of finding safety in anonymity, and of getting help from anti-racist groups based there. They found her a young left-wing lawyer, Ronald Reimann, to represent the rights of her child in the court case.

V he investigation into Kiowa's murder I was slow and ineffectual. The police I found it almost impossible to discover who had actually hit and killed him. One problem was that almost all the witnesses had been drunk at the time. More important still, almost all the witnesses were also suspects.

"The problem at the court was that there were no independent witnesses," said Reimann. "They had all gone to the Hiittengasthof to attack blacks. Afterwards they said they couldn't remember anything. Among them was a wellknown young Nazi from Eberswalde. But some of them were just juveniles." The state prosecutor, Henry Moller, said his investigators ran into "a wall of silence, ignorance, secret agreements, and cover-up."

Altogether the investigation took almost 18 months. I went to Frankfurt an der Oder, where the state prosecutor's office is located, to ask the chief prosecutor, Herr Lehmann, why it had taken so long. Lehmann, who came from the West, blamed the legacy of the Communist regime.

"The police and the prosecutor then were still from the G.D.R. They had never learned to handle this kind of violence. The G.D.R. was a police state in which people were suppressed and the whole society was controlled by the Stasi [secret police]. This was a new type of violence in the unified Germany. The police and judiciary had not learned to deal with it. That is why the whole thing happened." The police were afraid of re-creating the old days, when they frightened everyone. The public prosecutor had the same problem. He was insecure. He did not know how to respond.

Eventually five young men, bom between 1970 and 1973, were prosecuted, not for murder but for "Korperverletzung mit Todesfolge"—death following fatal injury. Lehmann seemed to think that this was the best that could have been hoped for. "Maybe more than 5 out of the 50 were responsible, but at least charges could be brought against 5."

The case would normally have been heard in Frankfurt an der Oder, where the prosecutor's office is located. But to demonstrate its importance to the people of Eberswalde, the authorities decided the hearing should take place there.

Two of those charged were brothers, Sven and Kay-Nando Bocker; each had a record for assault.

Kay-Nando had also been head of a neo-Nazi skinhead group. He ran away after being charged. During the trial he was caught in Stuttgart, where he had been working in a hotel, and brought back to Eberswalde, but since the trial was already well under way he could not be prosecuted. He appeared instead as a witness.

During the trial, another witness turned up in Nazi regalia. One of the defendants said, "The life of a black man has no meaning to me." But despite the clear evidence that existed, the judges ignored the accused men's ties to extreme right-wing groups.

The judges, two professionals and two lay people, were subsequently criticized for discouraging questions about political affiliations. "That was important to establish motive," said Reimann.

Last fall, four of the defendants were sentenced to terms of between two and four years for Kiowa's death. (The fifth was convicted of beating Armando Meque.) The maximum sentence would have been 10 years. The sentences were much lower than those demanded by the prosecution, and the commissioner for foreigners in the state of Brandenburg criticized them as "clearly too light."

The written sentences have not yet been delivered by the court. But when they are, the lawyers for three of the youths will appeal. Their grounds will be, in effect, that the court has been unable to prove that it was their clients who actually delivered any of the fatal blows.

In Eberswalde I went to see Alrik Kohrs, the aggressive young lawyer who defended one of the young men, Steffen Hiibner. During the trial, Kohrs and Reimann developed a professional antipathy toward each other. Kohrs objected to Reimann's asking about the politics of the accused. He also questioned Reimann's right to be in court at all, arguing that there was no real evidence that Kiowa was the father of Gabriela's baby.

"It's quite simple," Kohrs said about his plan to appeal Hiibner's conviction. "The sentence was a compromise, and not a good compromise. If the judges really thought they were guilty, then giving them only four years was a joke. But they were not sure. The case became such a public issue—with TV, radio, and the press. It was a very big case for the judges and all of us lawyers. There was a lot of pressure. It was a show trial, but not made for it."

Kiowa and his two friends were set upon by at least 15 of the drunken thugs. Many more stood about, cheering.

Kohrs maintained that the only fact that was established was that Kiowa was killed. "The statements were all contradictory. That is why the judges were uncertain. Some people were just standing around. Some were hitting and kicking. But who? In the case of my client I do not believe that the facts established his guilt. I shall appeal on those grounds."

A ivil-rights groups in Germany and I such international groups as Human V Rights Watch argue convincingly that the state's failure to prosecute forcefully the murder of Kiowa and many other cases has encouraged right-wing violence against foreigners.

Last year, one of the worst incidents took place at the refugee camp in the Lichtenhagen neighborhood of Rostock, a port town in northeastern Germany. The camp's reception center was situated in the middle of a working-class housing project, a location that was intolerable for both refugees and local people. Throughout the summer the number of refugees had grown, and by mid-August there were as many as 250 people camping in a field in front of the center. More and more small clashes and thefts were reported. Local residents were promised that most of the refugees would be moved. But nothing happened.

Then, on the night of Monday, August 24, 1992, protests outside the reception center turned into a violent rampage. At least 1,000 rioters, cheered on by an even larger number of bystanders, broke into a building housing about 100 Vietnamese contract workers, set fires, and began searching and destroying, floor by floor. The Vietnamese and the reception-center workers, who were on the seventh floor, moved higher up in the building as the smoke, the shouting, and the smashing rose toward them. It was hours before the police came and drove back the rioters. Eventually the Vietnamese were able to escape over the roof to another building.

The police had been warned since the previous Wednesday that an attack on the reception center was likely. But they took no action, neither ordering reinforcements to the area nor setting up checkpoints to stop armed right-wing "radicals" from entering Rostock.

Rostock was followed by Molln, in the West. There, last November, a 51year-old Turkish woman and two young Turkish girls were burned to death when their home was firebombed.

Molln is about as far from Eberswalde (or Rostock) as one can imagine. Eberswalde is decaying and rather desperate. Molln is smugly self-confident, part of the Hamburg region, which is booming as a result of reunification.

It is easy to blame unrest in Eberswalde, Rostock, and other eastern towns on despair and economic regression. But this "Officer Krupke" argument, as Josef Joffe, an editor at one of Germany's leading newspapers, calls it, cannot be applied to Molln.

T he Molln murders shocked Germany. I An army of police and prosecutors I descended on the town; within a week two young men had confessed to the crime and been arrested.

They were Michael Peters, a 25-yearold who was the leader of a small band of radical skinheads, and Lars Christiansen, 19. Christiansen worked as an apprentice in a supermarket, and had led an uneventful life. But Peters, an uneducated, unemployed skinhead, had long been under surveillance for violence against foreigners. Ten members of his gang had been arrested in the days before the Molln attack.

Neighbors said that his apartment, in a village a few miles frdm Molln, was a regular meeting place for radical rightists. He frequently threw loud parties with neo-Nazi music, and drunken skinheads shouting "Heil Hitler" out of the window and waving the German imperial flag.

Rostock and Molln received worldwide attention and forced German politicians to unite in condemnation. The government in Bonn banned first the Nationalist Front and then another neoNazi party, the German Alternative. Hundreds of police raided the offices of the German Alternative and its members' homes in six German states early one morning in December.

On December 10, Chancellor Kohl began a parliamentary debate by saying that Germany had a moral duty imposed by its Nazi past to act against extremists responsible for violence against foreigners. He promised "no leniency" toward the guilty. Of Molln, he said, "Whoever thinks they can change our land with a climate of intimidation and fear, they are fooling themselves. Germany is a democracy that can defend itself, and we will prove it now."

But the assaults also reopened the constitutional debate on Article 16—the asylum article—of the German Basic Law. Politicians preferred to seize on the issue of refugees rather than on that of growing right-wing violence. After much emotional debate, the constitution is now to be amended to place much stricter limits on the right to asylum in Germany. Some right-wingers are bound to see murder and rioting as having been highly successful tactics.

Germany's European neighbors watch with a sort of macabre fascination as elements of its past flicker across the present and attempt to direct its future. Magazines and newspapers are filled with articles about the neo-Nazis. But much of the reaction has been hysterical, even gleeful, displaying an almost racist attitude toward the Germans themselves. The rest of the continent is hardly immune from xenophobia: in Britain, 7,780 racist attacks were reported in 1991.

Though Germany is facing an unprecedented crisis of identity brought on by reunification, it is by far the most powerful country in Europe. The Maastricht Treaty, which is causing so much angst in Britain, Denmark, and even France, was, at one level, designed by Germany's European partners to lock it into Europe. But the reality is that Germany will dominate Europe, financially and then politically, with or without a treaty.

The shadow of Auschwitz still hangs over Germany. But no other government in Europe would have maintained such a generous asylum policy for so long. And in poring over the violence in the country, there is often an element of schadenfreude; we want to believe that the Germans are at heart really Nazis. There is an envy of their postwar economic achievements. And there is a kind of awful pleasure in saying, "There they go again. They never change."

In fact the changes are enormous. This is not 1933. There is no sign of a new Hitler. In 1933, near anarchy stalked the land. The economy was in ruins; between 1929 and 1932, the G.N.P. had fallen 35 percent. The population was cynical and frightened by the storm troops of all sides. Today there is violence again, but it is private and disorganized.

There is another hugely important difference. The murders at Molln provoked ordinary citizens to make personal and collective protests against the blackbooted thugs. At the end of last year millions of ordinary Germans took to the streets to demonstrate their outrage at neo-Nazi excesses, the attacks on foreigners, and the government's failure to confront either issue boldly. Nothing like that happened in the 1930s. In some ways the Germans are more sensitive than other Europeans to the implications of their history. And the public demonstrations may have had an effect: rightist violence seems to have diminished in the first month of 1993.

Germany has grave problems. But so does all of Europe. The Cold War and the division of Europe placed the whole continent in a kind of limbo from which it is now emerging in all its grief and glory—in all of its gory danger, too.

I went one evening to talk to kids at ■ the workers' flats just behind where I Kiowa was killed. One room had been made into a youth club, run by a woman named Ilona Kliickmann, who said she was there because of her Christian vocation. The room had a table and chairs, for playing cards, and some easy chairs. The atmosphere was relaxed; a constant stream of teenagers lounged in and out. Some of the boys were skinheads, some not.

Before this room existed, they had nowhere to go, they said; they used to hang around in the graveyard, steal cars, and beat people up. Their favorite music was by Guns N' Roses, Slime, and Nirvana. They did not like punks. Punks, they said, were left-wing, dirty, and stoned. "Skins are clean and want order in Germany."

A boy called Remo said only a few of them liked Hitler: "We just like the idea of a clean Germany for Germans."

Not one of them had a job. "Ilona is the only person here who works!" said a kid. They thought that since the end of East Germany everything had . gotten worse. Everything.

When I asked them about violence, they agreed that having this room had calmed most of them. But one girl said with a smile, "Some people deserve violence." Asked whether the problem of neo-Nazis would grow, a young man replied, "Yes, of course, if the economy doesn't improve. And if foreigners still get all the jobs."

Gunter Grass has argued that the violence against foreigners is above all poor Germans fighting their own lowly status. "The hate between Germans is the root of this violence. But they know that they cannot take on the other Germans, the stronger Germans, with their jobs and their money and their cars, so they go for the weakest. In many ways it is an expression of their own self-hate, which was bound to happen with reunification."

Before I left Eberswalde, I went to see Gabriela Schimansky again. Young Amadeu was bowling around the apartment. Gaby still has friends from the foreign community; I met several Angolan and Zairian workers there.

I asked her for photos of Amadeu; she had two and agreed to let me have them copied. One was a wistful, rather charmingly posed studio shot of him and friends taken at a local shop, Photo Grand. I found the shop on the main street, recently moved to larger premises. The woman behind the counter was kind about Amadeu. "He was a very nice, intelligent boy," she said. "It was so sad." She had the pictures copied in a couple of hours, and I took the originals back to Gaby.

"Iam thinking of going to Angola," she said, "to show my son to his father's family. A Dutch television crew might go with me. But I am a bit afraid. I am afraid that they might blame me for Amadeu's death. And I am afraid they might want to keep Amadeu.

"And I am afraid of the racism there. "

T he next day I took local trains through I Brandenburg, changing in the little I town of Bad Freienwalde.

In the station lobby a slim young man with long blond hair, wearing an expensive tight leather jacket, trousers, and thongs, was beating up another, older man while a third looked on. The blond and his friend were screaming abuse at their victim. I shouted at them to stop, and the third man tried to restrain his friend. All three were very drank.

The blond ceased pummeling the older man's bleeding face to sweep a number of beer and vodka bottles off a windowsill to the floor. He smashed one against a wall, and I was afraid that he was going to attack his victim with it.

Just then the police arrived: two men in their late 20s who seemed to be quite scared. They dragged the blond off and managed to handcuff his hands behind his back. They pushed him out to their car. Four or five other youths came out of the station pub, where they had been playing billiards. All were drunk. All tried to argue or threaten the police into changing their mind. The bleeding man disappeared. The police dithered, frightened and uncertain. One of the most drunk of all, a huge young man with a shaved head, began to threaten the police with his billiard cue. Fortunately, some of his less inebriated friends pushed him away. He was so drank he practically fell. He contented himself by pissing his beer against the wall of the booking office. A trail of urine ran down the length of the room. As my train came in, the police took the handcuffs off the young thug and appeared to be on the point of letting him go. They seemed to have no idea how to react.

All this took place at 4:30 P.M. on a wintry afternoon, in the last light of the day. The scene could have been played out in any seedy European town. But, just then, it was easy to see how the three police officers in Eberswalde had stood and watched while poor Amadeu Antonio Kiowa was kicked to death by similar drunks in the middle of the night.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now