Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE CAUTIOUS HEART OF P. D. JAMES

'VANITY FAIR Interview'

With the publication of The Children of Men, P. D. James, the grande dame of contemporary detective fiction, and Baroness James, the prominent public servant, find a new voice

LYNN BARBER

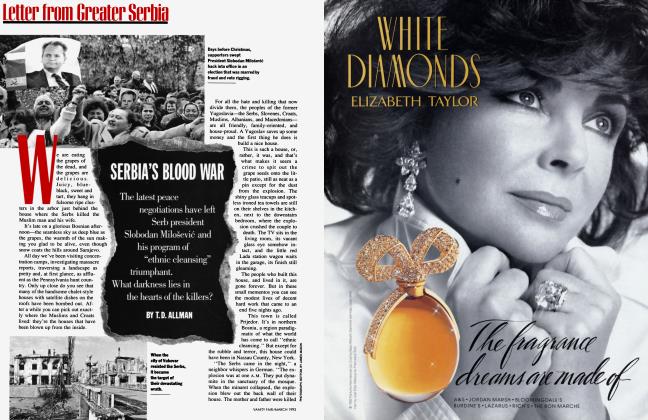

Can one writer single-handedly revive a whole literary genre? P. D. James appears to have done so. When she published her first novel, Cover Her Face, in 1962, the Golden Age of the Queens of Crime—Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Margery Allingham, Ngaio Marsh—was already over, and the whodunit itself seemed doomed to decline. Socially, it was hard, in the swinging 60s, to believe in those English country houses where the butler ushered in a cast of murderous gentlefolk and the amateur-sleuth hero, usually an aristocrat, discoursed about bloodstains while passing the port. The thrillers of the future would be less genteel affairs in which real policemen chased real psychopaths through real urban mean streets. Yet, in 11 elegant novels, spanning 30 years, Phyllis Dorothy James has re-created the classic detective story, and found a whole new audience through television. Her Commander Adam Dalgliesh (played by Roy Marsden) is a detective in the great tradition of Lord Peter Wimsey and Sherlock Holmes; admittedly, he is a professional policeman rather than a dilettante, but he is also a published poet who keeps a copy of Jane Austen by his bed and never passes a church without commenting on its architecture. James's suspects are as neatly balanced as Agatha Christie's but far more psychologically interesting; her corpses are quite spectacular, never killed by anything as mundane as a gunshot, but by, say, a blow from a madman's fetish, or the marble arm of a deceased princess. Her outstanding skill is to enclose her murders in totally convincing realistic settings—the psychiatric clinic of A Mind to Murder (1963), the Suffolk headland of Unnatural Causes (1967), the nuclear reactor of Devices and Desires (1989)—so that disbelief is suspended by the time one discovers that the place is inhabited entirely by murderers, blackmailers, and poison-pen writers.

But what of P. D. James herself? What does that strangely sexless byline conceal? Let us imagine that we are Commander Dalgliesh and that the woman in front of us is one of our murder suspects. Is she carrying a guilty secret? Could she have wielded the blunt instrument in the locked library? On the face of it, absolutely not. It is hard to imagine a more quintessential picture of respectability than this 72-year-old widowed grandmother, with her round, bespectacled face and plump, serviceable body, her sensible knitted two-piece and practical low-heeled shoes. But we should beware of that word "grandmother," with its cozily domestic connotations: herC.V. reminds us that we are in the presence of a formidable career woman. Baroness James of Holland Park, ennobled in 1991, started as a mere healthservice filing clerk, then took exams to qualify as a hospital administrator, switched to the civil service in her mid-40s when her husband died, and shot like a rocket through the ranks of the Home Office, ending as principal in charge of the Criminal Policy Department. On retirement in 1979, far from putting her feet up, she became a magistrate, an associate fellow of Downing College, Cambridge, a member of the Arts Council committee and the British Council board, chair of the Society of Authors and the Booker Prize panel, and a governor of the BBC. In the unlikely event that she should ever need a character reference, she could probably produce the English Establishment grand slam— the prime minister, the archbishop of Canterbury, the warden of All Souls College, Oxford, and the governor of the Bank of England. She hobnobs with Cabinet ministers; she lunches with the Queen.

And yet, asked whether she believes that most people have skeletons in their closets, she says with absolute certainty, "Everyone does." Which means, presumably, that she does too. It is at this point that you notice you can never really see her eyes; they are so deeply recessed behind thick glasses that they appear only as currants in a bun. She seems to be smiling, but for all you know she could be measuring where best to insert the ice pick, or when to serve the poisoned sherry. It is disconcerting, too, to notice that the only bookcase in her living room contains a complete set of Notable British Trials. And then there is the mysterious bunch of keys hanging around her neck: she uses them to unlock and relock the front door of her house in London's Holland Park every time anyone goes out, even for a minute. The house is well guarded with security grilles, and on a busy main road: she says she chose it because she liked the feeling of noise and bustle outside, and because it has a well-lit basement where no robbers can lurk. She also confides that she keeps a policeman's truncheon by her bed so that if a rapist got in she could defend herself. She thinks about such things—which Underground stations have elevators instead of escalators, which streets have insufficient lighting. In New York such worries might be considered normal; in London they amount to paranoia. This is a woman with an unusually strongly developed fear of violence, who sees the world outside as populated by robbers and rapists, by what she has called "this great surging morass of violence. Of evil." And the morass, of course, is the subject of her novels, that canon of mayhem and murder in which every dark, aberrant byway of human behavior is explored. P. D. James is not quite as straightforward as she appears.

'Oh, she is a ghoul merchant, definitely" says her editor. "She loves doing the gory bits.'

Her new novel, The Children of Men (Knopf), is another puzzle. It is not a detective story, but a bleak moral fable set in the future, a future in which the human race has become infertile and an elderly population waits to die. The idea for it came quite suddenly, she says, when she read a newspaper report that the sperm count in Western males had fallen dramatically in the last few decades: unlike her detective novels, which entail months or even years of meticulous plotting, this one came almost as a "given." It is more overtly political than any of her previous works, but the politics are not quite what one might expect. Broadly speaking, she is a Tory, though at present she sits on the crossbenches in the House of Lords (i.e., as an independent), so as not to compromise her position as a governor of the BBC. Certainly her conversation and her books show a generally right-wing cast of thought: she has scant patience with the idealism of the left, and considerable sympathy with the pragmatism of power. Yet in The Children of Men she seems to come down finally on the side of idealism, though not without a hint of skepticism about how this decision might turn out. The novel is also explicitly religious, expressing not only her usual aesthetic enthusiasm for church architecture and the King James Bible but also a deeper spiritual yearning for redemption through love.

What is surprising is that it has taken her so long to get around to writing her first "serious" novel. She always meant to, from her teens, but, finding herself with two children and a mentally ill husband to support, she didn't begin writing till she was 40 and then decided on the whodunit because it was popular and easily publishable. Cover Her Face was well received, and she stuck to the detective genre, producing her 11 novels at an average of one every three years, writing each morning before going to the office. Her big breakthrough to fame and fortune came with her eighth novel, Innocent Blood, in 1980. She had just calculated that she could afford to retire early from the Home Office—at Christmas 1979 instead of August 1980, when she would be 60—and that she had saved enough money to live on until she got her modest pension. "That was my situation on the Monday, and then they auctioned the American paperback rights and film rights, and by the Friday I was rich! But of course it's typical of life, isn't it? To those who have will be given, as the Good Book says."

Her novels have now sold more than 10 million copies in the U.S. alone and are published in a dozen countries. In 1987 she was awarded the Diamond Dagger Award of the Crime Writers' Association, for lifetime achievement, and she talks easily of her book-promotion tours, her signing sessions, her literary luncheons and lectures. But despite her now considerable wealth, she still lives like a retired civil servant. Her London house is in an expensive part of town, but of unostentatious size and decor—good prints and pretty china rather than important paintings and valuable antiques. The nearest thing she has to an extravagance is her house in Oxford, bought so that she could stay there and visit her daughter and grandchildren on weekends. It is typical of her self-containment that she would rather have her own house than stay with them—wanting not to be a burden to anyone is a recurrent theme of her conversation.

With all her public duties, she is probably even busier today than when she had a full-time job. Many fellow writers claim to be mystified by why she "wastes her time" on all this committee work, but James says firmly, "I would hate to be just in the literary world. I don't think it's good for you as a writer at all. It's a very narrow world." She has even said—although it seems almost incredible—that if she had to choose between writing and public service, she would choose public service. She obviously enjoys it, values the contacts it gives her, and is by all accounts extremely good at it. A friend who sat on a committee with her noticed that, although James often seemed to be in the minority, whenever it came to the vote she got her way.

Her upstairs office, with its neat rows of filing cabinets labeled BOOKER, BBC, BRITISH COUNCIL, is a bureaucrat's workstation rather than a writer's den—she prefers to write her novels at the kitchen table, in her dressing gown, before breakfast. But the actual writing takes less time than the planning and plotting, which she does on long solitary walks beside the sea, before making meticulous notes of timetables, room layouts, and so on. Extraordinarily, she writes her big set-piece scenes first, and then wraps the bread-and-butter stuff around them, "rather like knitting." This must make for enormous potential continuity problems, but Rosemary Goad, who has been her editor since her very first novel, says that she rarely makes mistakes in her plots, although "sometimes her geography is a bit suspect." With the early novels, Goad used to recommend cutting, but now James is allowed to decide her own length: Goad recalls that there was one particular description of a stained-glass window that she cut from one novel and found reproduced word for word in the next—and the next and the next, until finally she allowed it in. Goad has also sometimes objected to particularly gory touches, and James has sometimes, but not always, agreed to soften them.

Her absolute forte is the finding of the body, which she invariably describes with uninhibited relish—every wound and bloodstain and speck of vomit—using her trusty Simpson's Forensic Medicine to establish exactly where the blood clots should go. "Oh, she is a ghoul merchant, definitely," says Goad. "She loves doing the gory bits." James herself recalls that once, when she was being shown around University College, London, where the social philosopher Jeremy Bentham's mummified body is preserved, it "immediately" occurred to her that it would be a good opening for a novel to substitute the corpse of a senior lecturer for Bentham's. It is this dark imagination, this love of the macabre, that is so hard to reconcile with the brisk, sensible Baroness James one meets in person.

Does she fantasize about murdering people in real life? Does she sit in committee meetings trying to decide whether poison or strangulation would be the best way of dispatching a particularly tiresome colleague? "No-o," she says, not entirely convincingly, "but I do think there is quite a lot of aggression in me. I mean, if I were attacked, or if I were lying in bed and a rapist got in and I had a weapon, I don't think I would hesitate to use it.... I'm not a turner of the other cheek." But in real life she rarely hates anyone, and "it would be

'If a rapist got in and I had a weapon, I don't think I would hesitate to use it. I'm not a turner of the other cheek.'

very difficult if you did feel dislike of people you sit on committees with, because it's very disturbing, I think, to cope with." In fact, it seems to me that she suffers from an almost compulsive niceness, which must have been a handicap when she was running a civil-service department. She could deliver gentle reprimands but was never an enthusiast for the sport of tongue-lashing: "If I were really angry, I could probably do it, but I think I would find it rather frightening to be that angry. I would be much more likely to think: I must be careful about what I'm going to say, and do it on the basis of reason. But I suspect that what I did, the action I took, might be more fierce, more Draconian, than someone who gave them a tonguelashing. I think I would be quite unforgiving somehow—which I don't think is a very nice characteristic."

Asked—as she often is—why middleaged English gentlewomen are so good at murder, she usually says it's because they're observant and pay attention to the details. I asked, though, whether she thought hidden aggression came into it, and she agreed that it did. So perhaps, I suggested, if she had had assertiveness training at the age of 20 she would never have won her Diamond Dagger? It was meant as a frivolous question, but she took it quite seriously: "I don't think I ever needed assertiveness training, because—although I don't think I'm ever aggressive, and I am frightened of losing control—I really would find that terrifying. I'm very frightened of violence, in society and in myself—I know that. But I don't think I've ever needed assertiveness training, because most of my life I've got what I wanted. Maybe that means I'm manipulative?"

She once told an interviewer, "If I were reading myself, I would feel that here was a woman with such a strong love of order and tradition that she is obviously covering in her own personality some basic turbulence and insecurity." The trouble is that the turbulence and insecurity never come out in conversation. Her speech—like her house, like her clothes—is practical and prosaic: one gets a strong impression of intelligence, but not of imagination. She is a perfectly willing interviewee, but one who says discouragingly, "I always give the same answers. They don't change if you tell the truth." Asked the old chestnuts—about how she writes, or where she gets her ideas—she talks confidently and along well-practiced lines. Only when the conversation strays into more personal areas, such as her childhood or marriage, does she falter, and then her voice becomes so low, her speech so hesitant, her demeanor so distressed, that it takes considerable sadism to persist. Thus I suspect that we will know about P. D. James only what she wants us to know, and that the barrier between her public self and her private soul remains unbreached. It is astonishing how little even her oldest friends, like Rosemary Goad and her agent, Elaine Greene, seem to know about her private life, and especially about the 42 years before she became a published author.

(Continued on page 90)

(Continued from page 84)

She was bom in Oxford in 1920, the elder daughter of a medium-grade civil servant who worked in the tax office. Her parents enjoyed moving, and her father could easily get transfers from one tax office to another, so they lived successively in Oxford, Ludlow (on the Welsh border), and Cambridge. She won a scholarship to Cambridge High School, where she shone at English and was taught by a Miss Maisie Dalgliesh, whose name she would commemorate in her hero. She was happy at school, but not at home. She was not particularly close to her younger sister or brother, and there was a tension between her parents that she was always aware of. "I must have known that it was not a happy marriage. I don't think either of them was to blame: they were just incompatible." Her mother was warm, kind, demonstrative, generous, religious. "She would have been very happy married to a country clergyman, having a brood of children. She had great warmth and generosity. But then, you see, it didn't give her a great deal of happiness." Her father was much colder, sterner, and more intelligent. "A strict father, a fierce father really, or so it seemed to us then. As a child, I feared him.... I grew to know him when he was an old man and then I greatly respected the qualities he had: the intelligence and the rather sardonic humor, the independence and the courage, huge courage—these are qualities I very much admire. But they're not qualities that are important to a child. What a child wants is love and affection—oh, and approval, and generosity. My father was a very mean man. And, of course, as a child you don't see his problems. I mean, here was a very intelligent man who really had little chance in life; he had to start work at 16 in an income-tax office, which was hardly agreeable to him, then off to the First World War as a machine gunner, and then marriage to a woman who did give him some happiness, but who didn't much understand him." He consoled himself with golf and running a Boy Scout pack, which kept him away from home a lot. Even when at home, he often ate apart from his wife and children.

Phyllis, in consequence, was an anxious child. To get to sleep at night, she would imagine herself in a bed in a room inside a courtyard inside a courtyard inside a courtyard, with soldiers patrolling the outside. She developed the habit of thinking about herself as if she were a character in a story—"Then she got up, and then she washed," and so on—which was another way of keeping her anxiety at bay. She was not physically frightened of her father, but "I was frightened of his displeasure because I think my mother was very frightened of his displeasure, and I'm sure that we sensed this."

She says that she has never included any autobiographical material in her novels and never will. Though her settings are often real (and extremely vivid—she is brilliant at conveying the sense of place), her characters are all made-up. Nevertheless, she admits that Philippa Palfrey, the heroine of Innocent Blood, shares many characteristics with the young Phyllis James. Philippa is described as extremely clever, intellectually arrogant, but emotionally stunted, unable to give love: in fact, her cleverness seems to get in the way of her emotions. Her boyfriend urges her, when they make love, "Stop thinking about yourself. Stop worrying about what you're feeling. Let yourself go." But she cannot do so. Philippa has suffered an extremely unhappy childhood, but simply blotted it out of her memory. "She had survived those first seven years; she would survive this. And, after all, she wanted to be a writer. Someone had said. . . that an artist should suffer in childhood as much trauma as could be borne without breaking. And she wouldn't break. Others would break, but not she. There would be tatters and tom flesh enough on the barbed wire guarding that untender heart." What is particularly interesting about Innocent Blood is that it is all about the links between childhood trauma and adult behavior and is told with considerable psychological sophistication. Yet the real-life Baroness James—as opposed to P. D. James the author—is generally contemptuous of psychological theorizing and once told a television interviewer that she found it hilariously funny, when she worked in a psychiatric clinic in her filing-clerk days, to see that everyone's misbehavior was put down to their early weaning experiences. She probably thinks it is selfindulgent to "blame" one's childhood for adult problems.

'I was always 'much possessed with death and saw the skull beneath the skin.' I always felt I could die tomorrow'

As far as I can discover, she has made only one venture into autobiography, and that is a short article, "First Love," that she wrote for the London Sunday Times in 1975. The subject is not a natural one for her, and it is striking that even in this format—one of a series of romantic recollections—she cannot refrain from including a dead body. It is that of a drowned schoolboy, whom she and her first love, Robert, saw being retrieved from a river when she was 10. They feel the normal child's ghoulishness and excitement, and discuss what happens to people when they die. Robert tells her they go to limbo and she finds this a relief: she had thought it was a stark choice between heaven and hell. This finding of the drowned child seems to have been a psychologically significant moment in her life: the first conjunction of love and death. I asked if she subconsciously equated love with death, and she explained rather tartly that if she could tell me what was in her subconscious it wouldn't be subconscious anymore.

However, she admits that she has, and always has had, a strong fascination with death. "Yes, 'fascination' is the word. I don't think it's an obsession, it doesn't amount to that, but it's more than an interest, and I think it's been with me all the time. It's really an awareness of the reality of death, always, from childhood. An awareness that life was very short and sped past at this astonishing speed, and that this inevitable end was there for all of us. The young often don't think about it, because it's so far ahead, but I always did think about it. I was always 'much possessed with death and saw the skull beneath the skin.' I always felt I could die tomorrow. Whenever people said, you know, 'In three months we'll all be going on our summer holidays,' I would think, Well, yes, if we're all still here.

I don't think it overshadowed my life particularly; I didn't think it was likely that I would die, but I just was always aware that death could happen to anyone at any moment. And the huge finality of it, really."

In ''First Love" she describes her teenage self as ''a terrible intellectual snob." It was and still is a source of regret that she had to leave school at 16 and didn't go to university—she believes that if she had been a boy her father might have found the money to continue her education, but, instead, he installed her in a tax office, where she was wretchedly unhappy for a year. Then she got a job she preferred, as an assistant stage manager at the Cambridge Arts Festival Theatre, thinking that it might pave the way to a career as a playwright. Marriage had never been part of her childhood dreams. ''I can remember friends of my mother saying, 'One day you'll be married,' and feeling a sense of impatience. Marriage didn't seem to me terribly important." But then she met an Anglo-Irish medical student, Connor Bantry White, and married him when they were both 21. It was "slightly" an act of rebellion—she was eager to leave home, and the fact that it was wartime imparted a sense of urgency. She adds, "I wouldn't like to give the impression it wasn't a happy marriage. Until Connor was ill, it was a very happy marriage. I think he was the man I would have liked to have spent all my life with, and I think we did complement each other and I knew that. I am fairly dominant and I felt that I needed somebody who was very intelligent and sensitive but not masculine in an ambitious sense. I think I was probably the dominant partner. I mean, I didn't want a wimp, but I didn't want anybody tinged with aspects of the bully, which I hate. I always felt that I wanted a marriage in which I was going to be absolutely free—there would be no question that 'you can't do this' or 'you can't do the other'—that we should be a totally equal partnership. And all that I had with Connor. So had it not been for his illness I think it would have been good. It was good, for about three years. Well, I loved him."

Her husband had great charm, a sense of humor, and, as she once told the BBC radio psychiatrist Dr. Anthony Clare, "he was intelligent in a rather eccentric way. He was eccentric. I'm not sure that he should have done medicine—it was too much of a strain, I think." Mrs. Inge Steen, whose late husband, Terence, was friends with Connor White from their days as medical students at Cambridge, recalls him as "a delightful man, marvelously knowledgeable about literature, as happy as anything in a library. My husband said he was the best-read man he knew. But he was a very sensitive man, and I think perhaps he could not cope with all the suffering he saw in the war, and retreated into his own world." The Whites had two daughters, Clare and Jane, while he was doing his medical training; then he went off to war with the Royal Army Medical Corps. He came back a changed man. "He came back ill," James has said. "He returned and it was fairly obvious he was behaving extremely oddly. It took a long time to diagnose, but he never was mentally well from the time he came back." From then on he was in and out of mental hospitals, going from psychiatrist to psychiatrist, in hopes of a cure, which never came. The diagnosis was unclear, though it was probably some form of schizophrenia exacerbated by his occasional use of self-administered drugs. The army maintained that, although his mental illness had coincided with his war service, it had not been caused by it, so he was not entitled to a war pension. The young Mrs. White therefore found herself with two small children, a sick husband, and no money. She moved in with his parents, who were supportive throughout, sent her daughters off to boarding school when the younger was only four, and got herself a job as a filing clerk in the health service, while taking evening classes for a diploma in hospital administration. Typically, she won the regional prize in her exam, and moved steadily up the bureaucratic hierarchy.

'I didn't want a wimp, but I didn't want anybody tinged with aspects of the bully which I hate.'

But because she never knew what mood she'd find her husband in, and worried about how it would affect the children, her home life was grim. He was very fond of the children, and they of him, but it was difficult. James coped, but sometimes she was very near to breaking: "I had the job to do and I had to earn that money, so I had to keep working. It never occurred to me to run away. But I did certainly feel at times that it was too much. There were moments when he was home from hospital, when we were on our own, when he was obviously very disturbed and he would wake in the night and say, 'What have you done with Phyllis? What have you done with Phyllis?' which was very frightening, terrifying—him not knowing that I was Phyllis, thinking I was some strange woman."

Was he ever violent? "Never to me, but he was to himself. He threw himself out of a window once." She is deeply reluctant to talk about all this, her voice sinking into a whisper, a glint of tears behind the glasses. Asked if his death in 1964 was suicide, she concedes, in a whisper, "Probably," although the inquest recorded an open verdict. He had taken a mixture of drugs and alcohol, and she came downstairs one morning and found him dead.

His death still arouses very painful feelings. On the one hand, it was almost a relief because "1 think he felt that he would never be better, and it would have been wretched for him ending up in some mental hospital permanently. It would have been dreadful." But she told Anthony Clare that her sense of loss had not faded with the years; on the contrary, "it has become a very long and increasing grief. It wasn't so much a blow at the time. Indeed, it came at a time, a very difficult time, and I'm not sure how much longer I could have coped, really.

. . . I'm simply saying that I don't think at the time it was grief. I was very upset, very upset, but what has interested me is that I have continued to be upset. I have continued to grieve for him." She told me that she wished he had lived to see his grandchildren, and she added, "I still miss him, you know, miss him when he was well, and still feel fond of him. I realize now we would have been old together and it would have been very good." Even if he were mad? ' 'Oh... no. If he was going to go on as he was, it was better that he died."

She once told Selina Hastings of the Sunday Telegraph that "I'm not sure that even in my marriage I ever made the great emotional commitment." But now she thinks that that was unfair to herself. "I've certainly never wanted to make a great emotional commitment ever since. But I think I made the emotional commitment I was capable of making. I don't think I consciously held anything back at the time. Because if I hadn't made an emotional commitment, how could I have managed to stay with him all those years and worked for him and supported him and remained faithful to him? I suppose what I was thinking is that if you're a writer there's always something that is in a way detached from your own experience, observing it. I could observe even my own suffering with some interest. But if I look back on that marriage, and what it entailed, and what I had to go through, I couldn't have done it without a huge commitment—of loyalty anyway, and that's emotional commitment, isn't it?"

But one commitment was enough: she was never tempted to marry again, although she had offers. Instead, she flung herself into her career, feeling she could risk a more demanding job now that she no longer had her husband to worry about. She was quite happy to come home to an empty house. Like her hero, Dalgliesh, she has, she claims, a cautious heart. This is a quality that many of her fans regret in Dalgliesh: they wish he would fall in love. He sometimes shows a little stirring of interest, but it never comes to anything. But James, throughout her novels, seems to equate romantic love with foolish behavior:

more admirable in her eyes, and in Dalgliesh's, are the passionless virtues of intelligence, self-sufficiency, self-containment. It is hard to find a convincing portrait of a happy sexual relationship, whether heterosexual or homosexual, in any of her novels: in fact, it is one of the flaws of her plots that as soon as we find two people sleeping together we can be fairly sure that one of them is up to no good. In An Unsuitable Job for a Woman (1972), Cordelia Gray, the heroine, muses about sex: ''It was intolerable to think that those strange gymnastics might one day become necessary. Love-making, she had decided, was overrated, not painful but surprising. The alienation between thought and action was so complete." It is the indignity of sexual passion that seems to offend her most.

James agrees that she is generally skeptical of passion: ''I think that falling very greatly in love, very romantically in love, is dangerous, and often when I read of examples of it, I feel that it is something to be avoided. I mean, there are lots of examples of very talented women who've given themselves over to this great emotional love and they're HUMILIATED and PUT UPON!" But perhaps people in the grip of passion don't mind all that much how it seems to outsiders? ''I don't think they can do. But / would mind. I suppose they would say, 'The world is well lost for love.' That is the popular view, that the great emotional experience is worth paying almost anything for. Even the pain of loss, which is the worst pain, the pain of death, and the pain of betrayal. They think it's worth it to have experienced it. But I'm not sure."

She is generally pessimistic about love—and happiness. ''There may be a feeling of 'Beware of life if it gives you too much, or appears to give you too much, because it's not going to last.' The feeling that it's safer not to be too committed. Because if you are, you're going to get hurt. The only person who's not going to hurt you, or do treason to you, is yourself, really. I do feel that." It would be reasonable to assume that this feeling dates from her marriage, but in fact she says that even as a teenager she was not romantic. ''No, never. Never. Never very romantic. Never." In her ''First Love" article she admits that her first experience with a boyfriend ''taught me little, except, unconsciously, some of the subterfuges, self-deceptions and brutal emotional economics of love."

However, despite her distrust of passion, she does admit that the cautious heart has its drawbacks. "I think one of C. P. Snow's characters says, 'If you live your life as a spectator, it has great dignity, but if you do it long enough, you lose your soul.' " This is very much the central theme of The Children of Men. The hero, Theodore Faron, is an Oxford don who, like Dalgliesh, like P. D. James, values his emotional selfsufficiency, his frugal heart. He can be kind to other people but not committed to them. And then, in the course of the novel, he falls in love, hopelessly, onesidedly, and foolishly, and, by so doing, finds redemption not only for himself but also for the human race. The book is a very strong plea for love, for commitment: it reads to me like a recantation of all the emotional parsimony P. D. James has hitherto stood for. I told her I would not be surprised if in her next novel— and she promises that it will be a detective novel again—Commander Dalgliesh falls in love. She gave me one of her shrewd looks and shook her head. ''It would be so difficult, my dear! I know everybody would like it, and I'm not sure that he oughtn't. I think the splinter of ice in the heart had really better melt. But I'm not quite sure if I'm competent to melt it!"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now