Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEXIT PROSPERO

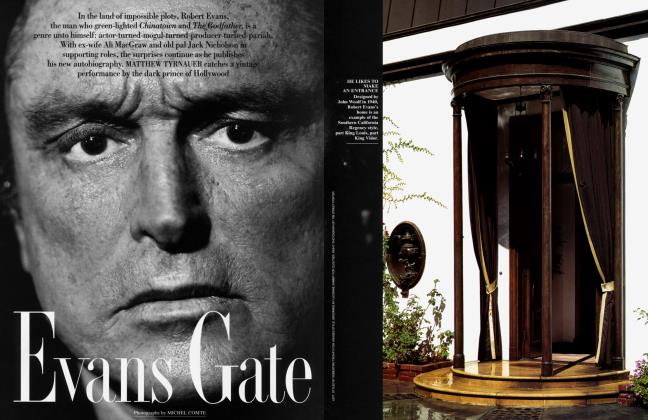

Director Tony Richardson was the wizard who transformed the English stage (Look Back in Anger) and screen (Tom Jones) and presided over a theatrical clan that included his ex-wife, Vanessa Redgrave, with whom he was planning a return to the West End. And as KATHLEEN TYNAN reports, Richardson faced his death from AIDS last November with the same style and wit that graced his finest work

KATHLEEN TYNAN

With the death last November of Tony Richardson at sixty-three, Los Angeles lost its most zealous partisan, the world of theater and film lost a very great and oddly unsung British director, and his extended family lost its own peculiar, profoundly humane animateur.

Hawk-nosed, as thin as a heron, with a voice like a run-down foghorn, Richardson was a man who once sighted and heard was not easily forgotten, who once known became an indelible and indispensable part of your life, generous beyond good sense, though likely, should you commit some act he perceived as treacherous, to cast you off his island like a cranky, whimful Prospero, until you begged to be returned.

To return to Los Angeles meant to return to Tony, with the promise of entertainment and argument.

When I arrived there a year ago, on New Year's Eve, I immediately called him.

What was I doing that very night, he wanted to know.

Would my daughter, her boyfriend, and I join him at the restaurant Spago? It would be a silly event, on a silly night. But it might be fun.

I had not seen him for some time, and was shocked to see that he was sallowcomplexioned and thinner even than usual. Of his AIDS-related illness, Tony spoke in the most peremptory way that night, as if he were detailing some mild and irritating impediment to his daily life. We ate well, we drank, and the clock struck midnight. To our table came the amiable wife of the patron, video camera in hand, to find out from each of us what we wished for the new year. My daughter drank to peace. I, sheepishly, to a romance. Then Tony lifted his glass and said, "To death! ' ' It was a salute, buoyantly delivered, not meant, I would guess, particularly for our ears. Did the Grim Reaper smile and bow? For sure he refused an embrace, and Tony stayed around for almost another year, living his life on his own terms, orchestrating a dozen projects, of which the last was a planned production in London of The Cherry Orchard, in which he would direct his exwife, Vanessa Redgrave.

The only drawback, he complained, was the necessity of leaving Los Angeles for his loathed homeland, a damp, dull place full of "sad," "dreadful" people. A place he had forsaken in the early 1970s, when he turned his back on one of the most dazzling and radically influential theater and film careers of postwar Britain to live in a decomposed granite pit and tilt his lance at Hollywood windmills.

In the mid-1950s he had joined forces with George Devine to create the English Stage Company, discovered John Osborne, mounted Look Back in Anger, and pulled the English theater reeling into the mid-twentieth century. Unsnobbish, contemporary, energetic, and brilliant, Richardson brought Lindsay Anderson and William Gaskill into the theater; discovered such actors as Alan Bates, Joan Plowright, Tom Courtenay, Rita Tushingham, and Albert Finney; and revived the career of Laurence Olivier. He launched a film company which developed the work of new writers such as Alan Sillitoe and Shelagh Delaney, with working-class subjects and backgrounds; directed such films as A Taste of Honey and The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner; promoted the careers of other directors, like Karel Reisz; and made a fortune with his Academy Award-winning film, Tom Jones.

He went on to make an arguably great movie, The Charge of the Light Brigade, and bad movies too, in a rollercoaster career which for some years left him without a hit, in a sort of obscurity —at least in the eyes of Hollywood. Recently Pauline Kael described Richardson as "one of the most gifted directors, and one who hasn't had the breaks he deserved." His movies, as another critic pointed out, were "made on his own terms, reflecting nobody's taste but his own."

"Vanessa explained to someone thatIas her ex-husband. and I said, I'm your only husband,' and she burst into tears, and then we danced!"

Richardson's friends try to explain that he lived out his own fantasy with precious little accommodation, that he was a person of extreme and forcefully expressed opinion (equivalent, in the land of the free, to bad manners). "Too original to be nice," according to the novelist John Irving, "not concerned with good taste, nor careful whom he offended."

He was a man of sharp mind, capable of brilliant flashes of insight, yet capable of boyish dogmatism. Terribly brave, morally and physically. (He was also, incidentally, badly coordinated, and a tennis lesson a day for a couple of decades did not turn him into a major player.) A man who rarely discussed show biz, and read more comprehensively than most scholars. Above all, a man for whom the present tense was more seductive than the past, and boredom, anathema.

His last film, Blue Sky, not yet released, was made under Orion's banner. It is a very fine piece of work, the love story of a professional soldier (played by Tommy Lee Jones) and his beautiful, sexy, and unbalanced wife (Jessica Lange), explored against a background of an atomic-test cover-up in 1960 and within the closed society of military life on the move from Texas to Alabama. Both actors are full of praise for Richardson. "Tony staged things," Lange explained, "so that they're cracking with energy." Tommy Lee Jones described him as an artist full of surprises, a director who included the actor in the process of filmmaking and who shaped the film as he worked. "It didn't take us long," he added, "to become an itinerant band of players."

With that, Tommy Lee Jones hit the nail on the head concerning Richardson's skill: selecting, corralling, galvanizing, choreographing, and celebrating a diverse group of people onand offscreen. The cinematographer Walter Lassally, describing the making of Tom Jones in his memoirs, confirms this: "End-ofpicture parties are quite common, but on this film we had a start-of-picture party as well, attended by all the crew and cast, which Tony rounded off by saying, 'Now let's go and have a lovely ten weeks' holiday in the West Country.' "

In December 1990 in New York, Tony produced another party: the marriage of his daughter, the actress Natasha Richardson, to the producer Robert Fox. After a civil ceremony performed in the apartment of Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne, some ninety guests gathered at an Italian restaurant on Lexington Avenue. From London came Tony Richardson's other actress daughter by Vanessa Redgrave, twenty-six-year-old Joely (since engaged to the producer Tim Bevan), and Vanessa's mother, the actress Rachel Kempson; his seventeen-year-old daughter, Katharine, and her mother, Grizelda Grimond; and his best friend, the inventor and engineer Jeremy Fry.

There was Vanessa Redgrave's onetime lover, the Italian actor Franco Nero, with their son, Carlo. There was Vanessa herself, flown in that morning on the Concorde from London. There was the actor Rupert Everett. There were the loyal friends from Los Angeles, and from New York a contingent of theater and film people—John Guare, Peter Shaffer, Martin Sherman, Lauren Bacall, Paul Shrader, Buck Henry.

Continued on page 146

Continued from page 133

Natasha had recently starred in a number of films—no doubt mindful of her father's instructions to her as he bounced her on his knee, aged three: "Movies, movies, movies." And Richardson, at that moment, was directing the party. He told the best man, the writer John Heilpem, that he was not to toast the bride and groom, but to introduce Vanessa, who would read a poem written by her sister, Lynn Redgrave, and would in turn be followed by Rupert and Grizelda. And so the performance proceeded, until it was Tony's turn to get up. Several of his friends were apprehensive. Had he not for weeks been making an incredible fuss over this speech business, his terror of taking the stage compounded by his exceptional distaste for marriage per se? ("Why spoil a perfectly good four-year relationship with a vow that changes everything?") But the show must go on, and the night before, he had told his beloved Natasha, when she asked how she should behave, "For God's sake, don't cry. It's not a day for parading your emotions."

Greeted by a huge ovation, he got up, wearing the first suit anyone had ever seen him in, for he normally wore jeans and sneakers, and began: "1 do not come from the performing part of this theatrical clan." He then proceeded to pay tribute to Robert's late father, Robin Fox, the English agent and producer (father also of Edward and James), and he ended by toasting "these two people, who are careening down the rapids of this ridiculous institution called marriage."

The speech was "so graceful, so meaningful, and so exactly right," Joan Didion reported, "that it just took your breath away."

Afterward, an accordionist played, and Vanessa—not one to remain in the wings— tied a napkin around her head and sang bits of "The Sound of Music," as well as the dread "Edelweiss" song and "Get Me to the Church on Time," helped along by Rupert Everett. Then she danced between the tables, and the whole room, under Tony's direction, drank and made a lot of noise.

The party over, the host flew back to Los Angeles, to his red wooden house in the Hollywood Hills, from where he could see the sun rise over downtown L.A. and watch it move over the Palos Verdes Peninsula and across the ocean and set behind the Santa Monica Mountains, a house of light, surrounded by a large junglelike garden planted with citrus, crepe-myrtle, palm, pepper, and jacaranda trees, a property with two swimming pools, a tennis court, and an aviary.

For a man who liked to celebrate the extended family onand offscreen, and loathed the solitary life, Richardson chose to live alone. Romantic and rash, he seemed always to be seeking new conquests and risking disappointment. I remember watching him at the Cannes Film Festival, some twenty years ago, chase a girl who happened to be in love and newly attached to another man. Unfazed, Tony asked her to go waterskiing, the only tactic he could find to remove her from the other man—a famously unsporting type. The problem was that Tony had never been on skis. Impressed by this foolhardy courage, and touched by his ungainly efforts to get up out of the water, the woman almost abandoned the love of her life in his favor.

He liked to conquer, and he liked to move on. Or so it seemed to me till he told me about another fiesta, an alfresco lunch he had hosted some time ago at the Hollywood house. It was in honor of the twenty-first birthday of Carlo Nero, who wants to be a director. The guests had gathered—sons and daughters, lovers and their lovers, polymorphous and mildly perverse, and, of course, the mother of the guest of honor, Vanessa Redgrave. There was a barbecue by the pool, and long tables on the grass alongside the aviary. Natasha cooked. Champagne was served, and afterward the guests joined hands and danced around the tables to the music of an accordion.

"It was really magical," Tony told me in his emphatic drawl. "I mean, it was one of those things that worked. Then Tasha decided it was Vanessa's and my silver wedding anniversary, and Joely proposed a toast to 'the only marriage in the family.' Vanessa explained to someone she introduced that I was her ex-husband, and I said, 'I'm your only husband' [laughter], and she burst into tears and sobbed [high-pitched laughter], and then we danced!"

I said that I thought that was wonderful, and I began to cry. Tony looked at me and continued to laugh his sardonic provocateur's laugh and asked, "What's wonderful?" And I said, "It's just very moving." "What's moving?" And he went on laughing while the tears poured down his face.

Tony Richardson met Vanessa Redgrave when she was a teenager, the daughter of famous actor parents, Michael Redgrave and Rachel Kempson. Richardson was already famous. A few years later, in April 1959, he directed a production of Othello at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in which Miss Redgrave walked on as a Cypriot. A year or two after that, he noted that the schoolgirl had grown up, and fell in love with her. She was equally enamored, and they lived together for several years before getting married, in April 1962. Vanessa was twenty-four; Tony was thirty-three—described in the press as "a one-man New Wave who put the kitchen sink on the map." Even after their divorce, they remained loving friends. While never much sympathizing with her politics, Tony always admired the intelligence of her work, her instinctive understanding of character, and what he described as her "absolute emotional truth, which just streams off whatever she does."

He used to advise her even when not directing her himself. In 1989, during the out-of-town run of Peter Hall's production of Orpheus Descending, Redgrave complained that she was unhappy with her performance. Tony told her to change from a southern accent and play Italian. Had not Tennessee Williams written the part for Anna Magnani? Vanessa changed her performance overnight and became a huge hit. His daughters would listen likewise. In 1984 he went to see Natasha in her first big London part, as Helena in A Midsummer Night's Dream. After the performance he went backstage and instructed her to drive him to the airport early the next morning. ''That's a bit rich, I thought," Natasha recalled, "having to get up early after my opening. In the car he told me, 'It's not enough to have a lovely voice.' He said I hadn't begun to think about the part. I was devastated. How could he be so cruel? A couple of days later he sent me a copy of the play underlined and noted. I no longer thought he was cruel, and my performance radically changed for the better."

Richardson always liked to be in control—of his family, of his cast and crew. "After all," he used to say, "I am a director. I can't do anything else. That's what I wanted to do since I was a boy."

Cecil Antonio Richardson was bom on June 5, 1928, in Shipley, a suburb of Bradford, Yorkshire, the only child of lower-middle-class parents. His father, whom he saw little of, was a pharmacist. His mother was a reserved woman who tried to draw her outgoing, civic-minded husband away from his public life. "I loved her, but she was totally enclosed and hardworked, looking after the household. Both my grandmothers lived with us, one with arthritis, a frozen old reptile, and the other nice. In addition, there was a maiden aunt or two. So I lived in the world of these old women, a life of total, absolute protection."

From a private day school, Tony was sent to a private boarding school, Ashville College, in Harrogate. There, at twelve, he directed his first play, Everyman, and there he suffered. "Ashville was horrors beyond horrors. Brutality, beatings, and bullying. It was just disgusting. The winter of 1939 was terribly cold, and there was no heating of any kind—just one prison blanket on the beds. We were ten-year-olds, and we used to get into each other's beds just simply for warmth. And one night the lights were flung on and this terrible headmaster raged in and dragged everyone out of bed and beat us savagely. We were told it was for 'rubbing up.' I hadn't the vaguest idea what that meant. I was keeping warm! The place was monstrous, and there was no education. I just read, and lived in my own world. But I learned that nobody can make you do anything you don't want to. I never played sports. I realized that I could just say no, and they could do two things, throw me out—which they weren't about to, because they needed the fee—or beat me to death, and they didn't dare quite do that! So they couldn't break me."

He went to the movies whenever he could. "I wasn't going to be a diplomat, or a lawyer, or a politician, as my parents hoped. I was going to be a film director, and the way to start was in the theater. ' '

When the distinguished theater director William Gaskill was a Bradford schoolboy, he joined Richardson's amateur group, the Shipley Young Theatre, and noted Tony's "elongated figure and squeaky drawl," as well as his ambition. "He was iconoclastic about anything that was sentimental and old-fashioned." On one occasion they were trying to raise funds for a show at the same time that Tony's father was running for election to the Tory council. "You've got to come canvassing for my father," said Richardson. "But I'm a Socialist," Gaskill objected. "Look. Do you want this production or not? It's the only way to get my dad to give us the money." The Shipley Young Theatre got its show.

In 1948, Richardson won a scholarship to Wadham College at Oxford and turned his back on Bradford for good. The director Lindsay Anderson remembers him as a sparkly, well-known character around the university, apt to do unexpected things. He became president of the Oxford University Dramatic Society and directed Marlowe's Dr. Faustus with bits of Tamburlaine added, set to the music of Wagner. He announced he would do Peer Gynt "all in rope." He advertised for a virgin to play Juliet, and eventually found her, or so he claimed, on a bus. According to the critic Irving Wardle, Richardson's "penetrating voice could be heard across the college dining hall, making declarations like 'I cannot bear Antony and Cleopatra. They are my noirest betes.' " Wardle noted that Richardson never seemed to get tired, and was "impervious to ridicule and incapable of losing his nerve."

William Gaskill, who followed Richardson from Bradford to Oxford, described his ubiquitous influence as devastating: "Creative and destructive, encouraging and disheartening, serious and flippant. Without him I would never have become a director."

At the end of his university career, Richardson spent four months in the United States on $100. The love affair was instant, he reported. "The second I arrived in New York I knew this was the country I could be at home in. I wanted to stay." Instead, the aesthete from Yorkshire went home and changed British theater for good. After taking a directing course at the BBC and mounting a few productions in small London theaters (he refused to do time in the provinces), he made himself known to the great teacher and director George Devine. Devine recognized in Tony what was in advance of the moment, and asked him to collaborate with him in the making of the English Stage Company at the Royal Court Theatre.

There were other farsighted people involved in this theater, set up to serve new writing, but it was Devine's vision, Richardson's choice of new and contemporary foreign plays, and above all Richardson's temperament that informed the company from its beginning in 1955 to his departure in 1966. His daring choice of material, managerial decisiveness, modernness, irreverence, and classlessness helped make the English Stage Company important and disliked.

From the start, the theater advertised for new plays. Of the hundreds that were forthcoming, Look Back in Anger, by an out-of-work actor named John Osborne, was selected. Devine saw the manuscript first. He read three pages and took it to Tony. "This might be interesting." Richardson read the play immediately. "It confirmed everything we were trying to do. Columbus knew there was something out there when he set out for America. We knew, too—and there it was when the play arrived."

In Jimmy Porter, Osborne invented a contemporary malcontent with whom the younger generation could identify. Here were the qualities which one young critic had been seeking in vain in English plays: "The drift towards anarchy, the instinctive leftishness, the automatic rejection of 'official' attitudes, the surrealist sense of humor...the casual promiscuity, the sense of lacking a crusade worth fighting for, and, underlying all these, the determination that no one who dies shall go unmoumed."

Richardson went on to direct Osborne's next plays, The Entertainer, in which Olivier played the one and only Archie Rice, and Luther, in which Albert Finney was catapulted to fame. Richardson's relationship with Osborne was always volatile, and Richardson was always the more understanding of the two. "John's an incredibly gifted writer, a great rhetorician. I'm fond of him, but he's a man of great viciousness. He's his own man and locked inside that very difficult personality."

In 1968, Osborne attacked Richardson, thinly disguised as a movie producer called K.L., in a one-act play called The Hotel in Amsterdam. K.L. is a ruthless, unstoppable creature, surrounded by con men and camp followers, "filling up on all of us, splitting us up." It is a touching irony that Osborne, staunchest of misanthropes, has now declared his love for Tony in his recently published memoirs: "No one has inflamed my creative passions more tantalizingly than Tony, nor savaged my moral sensibilities so cruelly. Whatever wayward impulse of torment he inflicted, his gangling, whiplash courage, struggling within that contorted figure, was awesomely moving and, at the last, unimpeachable."

Others whose careers Richardson propelled have responded as favorably. "We all benefited from his ruthlessness," Lindsay Anderson told me, "and his totally generous support of talent." The writers Arnold Wesker, Ann Jellicoe, Doris Lessing, Shelagh Delaney, and Nigel Dennis owe much to him, as do a vast number of established British actors, including Kenneth Haigh, Alan Howard, Nicol Williamson, Albert Finney, and the late Mary Ure and Colin Blakely.

At the Royal Court, Richardson directed seventeen plays between 1956 and 1964, introducing work by Eugene Ionesco and Bertolt Brecht as well as plays by Arthur Miller, William Faulkner, and Tennessee Williams. The critical response was often unfavorable, suggesting he was more impressive as an impresario than as a polisher of performance, yet he could always take his toughest adversaries by surprise with something brilliant, such as his fertile, Reinhardtian version of Pericles at Stratford, which he directed during the 1958-59 season, or his 1963 production in New York of Brecht's Arturo Ui.

Richardson had prepared his film career even before he helped launch the English Stage Company; he was a member of the Free Cinema movement, founded in the mid-fifties, which demanded a new aesthetic for British movies and which was influenced by the realistic backgrounds of early British documentaries. Tony wrote for the film magazines in which these ideas were explored, Sequence and Sight and Sound, and in 1955, with Karel Reisz, he co-directed Momma Don't Allow, a short film set in a jazz club. The anti-commercial Free Cinema movement merged with the ideologically committed Angry Young Men, noisily celebrating working-class culture. But it was Tony Richardson who put these ideas onto the screen: in 1958 he formed (with John Osborne and Harry Saltzman) Woodfall Films, and launched his first two movies, Look Back in Anger (with Richard Burton) and The Entertainer— shot on location and influenced in style by the French New Wave. By 1962 he had shaken off the theatrical stiffness of his first two films and directed two further explorations of working-class life, A Taste of Honey, about an unmarried mother, and The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, about a Borstal boy (from a story by Alan Sillitoe). He also made possible, under Woodfall's banner, Lindsay Anderson's This Sporting Life, Karel Reisz's Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, and Richard Lester's The Knack.

It is not surprising that Richardson had little time for the formulaic American films of the thirties and forties (though he was a great admirer of John Ford). "You can't compare them to the work of Jean Renoir, or early Italian neo-realism, or Japanese film—movies made in real places, with actors working in real conditions."

By 1962, Tony was shooting Tom Jones in the West Country while Vanessa was at Stratford giving her legendary performance as Rosalind in As You Like It. The stage designer Jocelyn Herbert recalls her coming on location and longing for a quiet time with her husband. Instead, he would be surrounded by cast and crew. "She was starry-eyed, besotted by him, and it was tough on her. It took her quite a while to realize that Tony would always be surrounded by people, and that life was not going to be as she'd imagined."

The Richardsons moved into a handsome London house, 30 St. Peter's Square in Hammersmith, which cost £25,000. Their first daughter, Natasha Jane, was bom in 1963. She remembers the doves, the toucans, the jungle-type garden, and the painted cupboards of her nursery, for this was the prototypical Richardson house. "My mother is notoriously bad at decorating," Natasha explained. ''When they moved in, Papa challenged her at poker, to decide who would get to decorate each room. Of course she didn't win a single hand."

In 1963, Tom Jones was released. John Osborne had written the script from the Fielding novel, and Richardson had put together a fine cast, led by Albert Finney, to make an entertainment full of quick gags and set pieces—Hogarthian, full-blooded, and sexy. The project had been given the go-ahead by David Picker, head of production at United Artists. It cost $1.3 million and made $30 million. Picker subsequently described Richardson as ''a consummate filmmaker, sometimes destroyed by his choice of material."

Tom Jones gave Richardson carte blanche to do what he wanted, and he chose to make Evelyn Waugh's The Loved One, about the American funeral business. Christopher Isherwood and Terry Southern worked on the script, and the cast included John Gielgud and Liberace. The gags, according to the critic Kenneth Tynan, came close to "the trip wires that separate effrontery from embarrassing overstatement." But this black comedy was unarguably innovative, and is viewed today by Buck Henry as "a great curiosity piece, done, as with everything of Tony's, with impeccable style."

In 1965 he began work on the film Mademoiselle with Jeanne Moreau, from an original script by Jean Genet. Moreau rather improbably played a repressed spinster, and shooting was not made easy by the fact that Richardson fell in love with the beautiful half-English, half-French star. "She's the greatest cinema actress in the world," he told the newspapers. "There's nothing she can't do."

"I was absolutely infatuated," he told me. "Jeanne was very exciting sexually, very interesting, and unlike other people. She was just a totally different kind of woman. Vanessa went through a very tough period. She was pregnant with Joely. She was still in love, and I was not. At one point she set off for China, then decided to try and come back to me. She got as far as Moscow, and got off the plane. But she didn't have a visa, so they threw her in jail."

Redgrave appeared as the deserted woman in Richardson's second film with Moreau, The Sailor from Gibraltar, an ill-fated, hastily shot production based on a story by Marguerite Duras. The two women had no scenes together, and Redgrave behaved impeccably throughout the drama.

Had Tony wanted to marry Moreau? "No. Oh, no. Never. I had no illusion that it was going to be a long relationship. I knew Jeanne had had an immense amount of experience, and was going to go on having it. Later, when I was very unhappy with Jeanne, Vanessa was very supportive."

When news of divorce proceedings broke, the press found Tony rehearsing Vanessa in a segment of the film trilogy Red and Blue.

After the two films with Moreau, Richardson surprised his critics with what many consider his masterpiece, The Charge of the Light Brigade, a quasi-absurdist vaudevillian epic take on the Crimean War, written by Charles Wood and shot by David Watkin, with animated interludes by Richard Williams. (Richardson banned the critics from the opening, describing them, in a letter to The Times of London, as "a group of acidulated intellectual eunuchs hugging their prejudices like feather boas.") John Gielgud, Trevor Howard, and Vanessa Redgrave starred.

The film came out in 1968, the year of the student riots in Paris, the same year that Tony announced that it would be a "super idea" if there were red flags on every Oxford college. "I was never a Communist," he later disclosed. "I'm an anarchist, with no real interest in politics."

His life-style was decidedly un-Communist. He now owned a house in Egerton Crescent in South Kensington, an apartment in a fifteenth-century palace in Paris, and a restored peasant hamlet in the South of France on the wooded hill north of Saint-Tropez called Le Nid du Due, near La Garde Freinet.

At Le Nid du Due in the summer, Richardson presided over a house party of about twenty people, who would gather for meals at a long trestle table under the trees. Over the years you might have found Jack Nicholson, David Hockney, the wife of the head of the French foreign service, Lee Radziwill seated alongside a toothless cleaning lady from the local village, John Gielgud, Jessica Mitford, Rudolf Nureyev, two or three hairdressers from Los Angeles, the local tennis coach, and everyone's children, including Tony's three daughters.

While Tony reigned over Le Nid du Due, that other great host of the region, Sam Spiegel, would hold court on his yacht in the harbor of Saint-Tropez, and once or twice during a season Tony's raffish crowd would descend upon Sam's sedate boat crowd and then beat a hasty retreat. Spiegel could never figure out why anyone wanted to go up a dust track to Richardson's place, and refused to climb the hill until very near the end of his life (in 1985), when curiosity got the better of him and he accepted an invitation to lunch. A particularly good meal was prepared in his honor. (Tony always used to go down to the market in Saint-Tropez at dawn, and bring back giant trays of Cavaillon melons and peaches and haricots verts, along with fresh loups de mer and tartes tropeziennes.)

We all waited nervously for the arrival of Spiegel. He was late. Just as we were beginning to give up on the elderly tycoon, one of the children spotted him walking ahead of his chauffeur-driven car along the precipitous, rock-strewn approach to the main house of Le Nid du Due. Slowly he came up to us and accepted a glass of house wine. "My chauffeur couldn't make it with my weight," he said. It was an inspired piece of one-upmanship, and Tony was absolutely delighted.

Just as Tony made Spiegel perform, so he demanded performance of everybody else. "You see," my children used to explain to me, "he's a dramatist." From an early age, Joely and Natasha starred in Nid du Due productions initiated by their father. There was the musical of the life of Saint Tropez, written by the playwright John Mortimer, lit by Tony, which concluded with a flock of doves released from garbage cans placed around the swimming pool to the sound of Handel's Water Music. There was the performance of Gypsy with Natasha starring as Rose, and Joely as Gypsy, backed up by a chorus consisting of the wives of John Mortimer and John Osborne and a transvestite from Milan.

David Hockney remembers Natasha, aged ten, gesturing histrionically and declaring, "I'm not going to be an actress!" Fat chance, he said to himself. On one occasion Vanessa Redgrave came to stay, during rehearsals for A Midsummer Night's Dream, and made all the children playing fairies miserable by dressing them as poor scavengers when they wanted pretty costumes with wings. Tony saved the day by deciding instead to do a comic scene from the play, in which he played Peter Quince, and Vanessa's boyfriend, Timothy Dalton, Bottom.

And always up at Le Nid du Due there was a combination of lovers old and new living in reasonable harmony to the infinite dismay of the married men unable to conceal one paltry mistress. It would be wrong, though, to conclude that Tony was an entirely benign ruler of his island. On occasion he was more Ariel than Prospero, and he liked nothing better than to stir up a drama; if people burst into tears, he would simply look surprised. "What he liked," one actress explained, "was to pick on someone. You knew your turn was coming and you had to brace yourself. Sometimes he'd draw out a story from you you didn't want to tell, about someone you'd slept with years before, and you'd tell the story in front of this gauping group of people."

"His great fear in life was boredom," the wife of a famous playwright told me. "He once drove my husband to the airport in Nice and returned with me to Le Nid du Due. 'I suspect you hope he has a plane crash, don't you?' Tony said. 'Then you'll be a nice rich little widow.' " The loving wife was very shocked.

On another occasion Tony played the detective in a game of murder. When the lights went up for the interrogation, he told one pretty teenager that he was sure she wasn't the murderer—he'd seen her flirting with Roman Polanski. "I don't want to go into details," he went on, "it was too disgusting." The particular Lolita under fire burst into tears and fled, declaring, "How could you think I've been with that old man?" Tony was very pleased, and Polanski sat there like the cat who ate the canary. The rest of the guests didn't know whether to laugh or be angry, till Tony tipped the mood and made magic again.

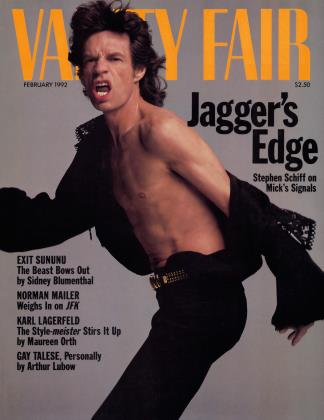

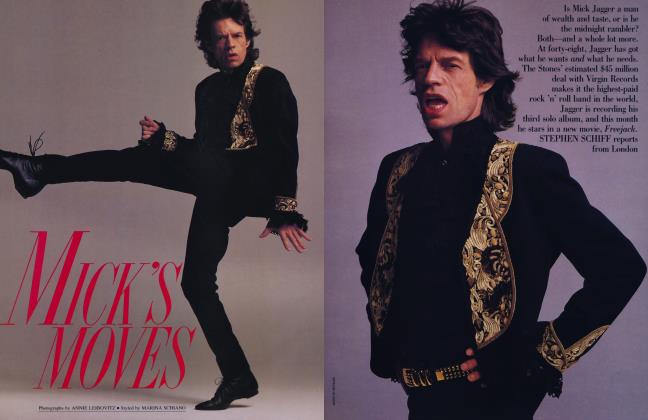

Vacation drama, of course, was a pale substitute for the real drama, making movies. Only on a set was Richardson completely happy. After The Charge of the Light Brigade, he made five movies (including Ned Kelly, starring Mick Jagger), not all successful. In 1977 his second homage to Fielding, Joseph Andrews, came out, but did not restore his commercial reputation.

In 1982 he made The Border with Jack Nicholson, an impressive, muckraking story of a border-patrol officer policing illegal Mexican immigrants on the Rio Grande. Nicholson admired his work; Richardson in turn admired Nicholson and learned a lot from him about action. "There's a fineness about Jack's taste as an actor that there never was, for example, with Larry Olivier's. Larry was a very stupid man with wonderful instincts, but he never surprised me."

Richardson's next feature, The Hotel New Hampshire, from John Irving's novel about the eccentric Berry family (with Jodie Foster and Rob Lowe), was released in 1984. The film suggests that a family can transcend the violence and hate in the world. The piece was not liked, except by a few devotees who believe it was misunderstood.

In the last few years Richardson made two courtroom dramas for television, as well as a mini-series on Beryl Markham and The Phantom of the Opera, with Charles Dance and Burt Lancaster, all of which were praised. He also shot a short film for HBO of Hemingway's "Hills Like White Elephants," with a script by his friends Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne.

Several years ago Richardson commissioned Alice Arlen to write a screenplay of Didion's novel Democracy, which he subsequently rewrote. (He always worked on his screenplays.) "If I do one thing before I die, I want to make Democracy. It's just a perfect subject for a real romantic love story and a big commercial success. It isn't political at all," he added, which came as rather a surprise to those of us who had read the original.

Meanwhile, there was a life to be led, a new shipment of exotic birds to be viewed down in the Los Angeles harbor, a falconry meet of the California Hawking Association up in Los Banos, a visit to an art gallery, or a longer visit to a distant place with Jeremy Fry. Tony was always a serious and intrepid traveler. A few months before he died, I asked him, Where on the planet is magic? "Paris, Le Nid du Due, of course. Italy, the slopes of Everest, Sri Lanka, Bali. Some of Thailand, lots of Brazil and Mexico." And where is hell? "Anywhere north and cold" came the answer. And L.A.? "L.A.'s not magic, but it's the only great capital city where you can live out-of-doors." And when you're too old for tennis? I asked as we picked up our menus at Spago. What about getting old? "That's just something you accept," Tony answered, as if to deflect the shadows of mortality. He glanced down at his menu. "Never order lamb," he said. "It's a very dirty meat."

On November 14, around 1:30 P.M., Tony died in what he had ironically referred to as "the Garden Suite" of St. Vincent's Hospital in Los Angeles. His family, including Vanessa Redgrave, were at his bedside. There was no funeral, no memorial service (his ashes will be scattered at Le Nid du Due), just a party up at the house. It was directed, of course, by Natasha. Tony had been particularly fond of a small tank of tropical fish in his hospital room. So huge colored paper fish were hung from the rafters of the living room. There were lavish white flowers, and above the fireplace a blown-up photograph of Tony, wearing a Stetson and directing a movie. It was a crowded party, a strangely happy one, to send this irreplaceable man on his way.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now