Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTOKYO PROSE

Picking the wild cherry blossoms of a new wave of Japanese fiction

Mixed Media

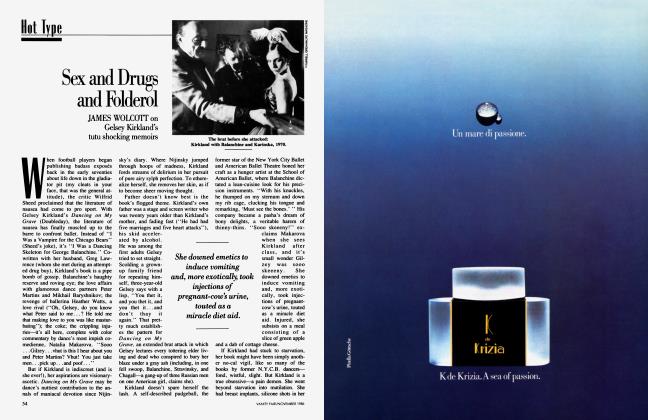

JAMES WOLCOTT

'The Japanese are coming, the Japanese are coming," intoned mad-bad Miles Drentell (David Clennon), on thirty something, courting an infusion of Japanese funds into his ad agency. Or should I say injection? He had a junkie's jitters. To some, this typifies America's plight. We've become a winkle of weak resistance. Alarmists see the swarm of Japanese money power as another Pearl Harbor. Only this time we go down not in flames but in a flurry of sales slips. Even with the nosedive of the Nikkei, the Japanese have been buying hotels, golf courses, movie studios, and Impressionist paintings; pocketing Hawaii as their private holiday resort; packing the drinking fountains of Washington with Ninja lobbyists; running a protectionist racket at home. Do we want them to own us? Japanese culture has been characterized as rigid, rape-happy, irreligious, morbid, copycat, codified, xenophobic, hierarchical, and ancestor-haunted, an empty precious shell clasped in a cold hand. Their music whines like mosquitoes, and their theater is a glacial frieze. Yet they proliferate. Jap-bashers can't figure. Didn't we drop a coupla bombs on these people? asks that great American Andrew Dice Clay.

An antidote to this outbreak of Yellow Peril is the influx of English translations of Japanese fiction inundating our bookstores. Classic and current Japanese fiction alike correct the notion of the Japanese as a robot race, a beehive of modular subcompacts. They don't seem that different. It certainly punctures the pretty picture of Japanese women as submissive misses. They have the unleashed hair of succubi.

Japanese authors have been accused of dabbling with slow drips of blood and semen. ''[They] make less of a fuss than American authors about the distinction between literature and hack work," writes David Mura in his forthcoming memoir, Turning Japanese (Atlantic Monthly Press). "Mishima wrote soft porn and potboilers as well as Confessions of a Mask. Twenty years after his death, the standard complaint now is that all Japanese authors write is soft porn." Why soft? Because sex in Japanese fiction isn't a bulging fist beating at the church and bedroom door. It isn't performance-oriented, as it is in the phallic funrides of Henry Miller or Erica Jong, where the purpose is to ring every bell on the orgasmatron. Without being wimpish, Japanese fiction focuses less on conquest and entry, more on entwining and completion. Ego is rinsed of its bloodshot bluster. The eye swims through wavy auras. Erotic rapture is diffused and dispersed, flushed at the cheeks, dewdropped at the earlobes, twigged to the fingers and toes. Especially the toes. It's been said of Junichiro Tanizaki that his men worship the feet that trample them. No better place to begin than Tanizaki's Naomi, recently reissued in a handsome paperback edition by North Point Press.

A classic comedy of enslavement, Naomi is about an office drone who falls for a cafe hostess. Naomi is fifteen; Joji is twenty-eight. His plan is to sun this bud into full flower. But although Naomi resembles petal-faced Mary Pickford, she behaves like Louise Brooks's hellcat, Lulu. Hedonism incarnate, she doesn't have the stooped posture of the Japanese past but the arrowy physique of the Western future. Her would-be teacher finds himself tamed. Installed in a little love nest, Naomi makes Joji crawl on all fours as she rides him around the room. "For reins, she made me hold a towel in my mouth." After she abandons him for a pile of other men, he heaps her clothes on his back and plays horsey by himself. It's like Emil Jannings's humiliation in The Blue Angel, but friskier, without all that gargoylism. When Naomi agrees to return to Joji, it's on her own high-titty terms. Why does he accept? Near the end of the novel, Joji begs Naomi to saddle him again. She leaps savagely on his back. " 'Satisfied?' She spoke like a man." With Naomi he need never leave the closet.

His characters are always trying to find the right plug for their kinky outlets. The latest Tanizaki translation, A Cat, a Man, and Two Women (Kodansha), contains a story about a professor pursuing a dancer with a missing toe and a speech impediment. It ends with him

fitting her with a fake toe made of wax or rubber. He asks if it hurts. "Whny nho," she says, "hinht doesnh't hurnt ha binht.'' Such a kiddo indulges Daddy's sexual hang-ups in order to enjoy household comfort. As Tanizaki's characters age, the gamesmanship becomes brinkmanship. The Key (Wideview/Perigee) concerns dueling diaries kept by a professor and the wife he pushes into infidelity. She uncorks with such thrashing abandon that her husband has a stroke. In Diary of a Mad Old Man (ditto), a seventy-seven-year-old wheezer is cockteased crazy by his daughter-in-law. "1 pressed my lips to the wet sole of her foot, a foot that seemed as alluringly expressive as a face." After each arousing episode he has his pulse taken by a concerned nurse. It's like a running gag in a vaudeville sketch. Oh, nurse! The payoff is that as the old man prepares to pop he requests that his tombstone feature carvings of his daughter-in-law's tootsies. That's heaven for a Tanizaki man, lying permanently beneath a woman's feet.

Suppliant sleep reaches a postponed state of ravishment in the writing of Yasunari Kawabata. In the novella House of the Sleeping Beauties (Kodansha), an old man spends a series of evenings with nubile girls left nude under a quilt. They are drugged before the customer arrives, and he leaves the next morning before they can awaken. It's an idyll of eternal innocence, of ripe suspension and pure contemplation. Because no actual sex takes place between the old man and the sleeping beauties. No funny stuff, the madam has warned. He can only stay on the peachy surface. Entranced, he studies their mute forms like maps, like physical Sanskrit, deducing their lives from their puffs of breath, the tremble of their eyelashes, the outs weep of their limbs. He eventually shares a bed with two sleeping girls. "A spasm came over to him, as if to say: 'Initiate me into the spell of life.' " The novella itself is a spell, an amazing feat of awe. The raptness extends to The Old Capital (North Point Press), which ends with twin sisters who have been separated since birth sharing a sleepover one winter's night. They seem encased like tiny embryos inside a Christmas paperweight. Daybreak brings a second separation as the snowflakes settle to the bottom. Twinship is the theme of this novel. The Old Capital is about making peace with your secret self. Not all of Kawabata's female characters are recumbent. Keiko, the painter in Beauty and Sadness (Wideview/Perigee), is a Naomi-ish mantrap. Asked if she would ever sacrifice an ear for her art, a la Van Gogh, she says, No, someone will have to bite it off.

There's an intense twilight to Japanese fiction which pearls even the playful sex with a wistful pallor.

Kawabata may be one of the leastknown great writers of this century. The knock on his writing is that it can be as faint as ground fog. Even sympathetic critics have called his work elusive, enigmatic, oblique, unresolved. Too inaccessible for Western readers, they sigh. Ah, the inscrutable East! Such critics prefer the magic beans curled in

his Palm-of-the-Hand Stories (North Point Press), which they compare to Borges. I think they're screwy. (But then, I'm not big on Borges.) In his novels he's a great fadeaway artist, reaching his emotional effects with a self-effacing momentum that carries him out of the frame. He never tries to impress the reader with fancy preparation. The fire-storm climax to Snow Country (Wideview/Perigee)—a masterpiece—has the force of a natural calamity.

Perhaps Kawabata suffers from the curse of having won the Nobel Prize in Literature. According to one theory, he received the award in 1968 because the committee was determined to honor a writer from Japan (they tended to rotate countries) and he filled the spot left by the death of Tanizaki. A common suspicion remains among readers that a Nobel Prize winner will be full of craggy uplift about Man not merely surviving but prevailing. (The words of William Faulkner, Nobel honoree, 1949.) Is Kawabata a cliche humanist? Anything but. Sensual as it is, his fiction is a bleak summons. It reflects the downpull in his own life. One day in April 1972, he left home, entered his office, turned on the gas, and died. "There was no farewell note,'' writes Donald Keene in Dawn to the West, "and the reasons for his suicide are unknown.'' He whited himself out.

In contrast, his contemporary Osamu Dazai left quite a paper trail. An addict and alcoholic of anarchist bent, Dazai feuded with his literary elders. He threatened to stab Kawabata, who had called his writings the soliloquies of a deviant. Like Mishima, Dazai made suicide a spectator event. It took this bughouse hepcat numerous tries before he finally nullified himself. In 1930 he attempted the first of his "love suicides," with a married waitress he barely knew. They took overdoses of sleeping medicine together and were soon found sprawled on seaside rocks. He survived, she didn't. Later he resorted to rope. "Being able to swim, it wasn't easy for me to drown myself, so I chose hanging, which I'd heard was infallible," he writes in Self Portraits (new from Kodansha). "Humiliatingly enough, however, I botched it. I revived and found myself breathing. Perhaps my neck was thicker than most." Years later he attempted another love suicide, this time with his wife. Both survived. He finally got it right: on June 13, 1948, he and a young widow named Yamazaki Tomie attempted double suicide at the Tamagawa Canal. They both drowned. A photograph in Self Portraits shows Dazai sitting on the banks overlooking the very waters that would claim him. His body was discovered on June 19—his birthday. He would have been thirtynine.

Does anything redeem such scattered wreckage? His humor, I think. He had a cheerful sense of the damned. "I was the basest, most reptilian young man in Japan," he writes of one penniless period which found him peddling "suicide notes" to Tokyo editors. After he had become a star, with the success of his novel The Setting Sun, he was photographed at an underpass sheltering a homeless group. "Walking through that place, the one thing that struck me was that almost all the bums lying there in the darkness were men with handsome, classical features. Which means that good-looking men run a high risk of ending up living in an underpass." And since he's a handsome devil himself, he qualifies. He later shows his wife some shots.

She studied one of the photos and said, "Bums? Is that what a bum looks like?"

1 got a shock when I happened to notice which face she was peering at.

"What's the matter with you? That's me. It's your husband, for God's sake. The bums are over here."

My wife, whose character is, if anything, excessively serious, is quite incapable of making a joke. She honestly mistook me for a bum.

But he doesn't sound too displeased.

It would be a crummy shame to leave the impression that the only good Japanese writer is a dead Japanese writer. Still among the living is Shusaku Endo, born 1923. A rarity in Japan, Endo is a Catholic intellectual who has lifted his eyes to the cross to write a life of Christ. His novels carry the endorsement of fellow Papist Graham Greene, who called him "one of the finest living writers." The story of a laureled author who discovers he has a depraved doppelganger (his double is spotted in Tokyo pleasure spas, getting his kicks being diapered like a baby!), Endo's Scandal (Vintage) has its Greene shades of comic nausea and neon menace—a squeamish sense of sin. But as its hero crouches at the keyhole, its contemplation of sleeping beauties becomes pure Kawabata. "There was no surplus flesh on her abdomen; her navel was a long, narrow slit like a faint indentation in the billowing rise of a sand dune." Women are a foreign land. The sweaty twist to Scandal is that the author's double then enters the girl's room, giving vent to the author's repressed wishes, only to be subdued. Scandal is about making war with your secret self. Being Catholic, Endo sees the secret self as a soiled intruder. "[He] was certain as he had watched through the peephole, thanks to the magnifying lens, that he had seen lines of saliva, like slug trails, glistening on her body." Last year Simon and Schuster published Endo's Foreign Studies, in which a Japanese scholar alone in Paris consumes the corpus of the Marquis de Sade like a bowlful of worms. He dies of this diet. Across cultural frontiers, some dishes don't travel.

Endo is an eminence. Making chicklike cheeps in the background are the contributors to New Japanese Voices (out this month, Atlantic Monthly Press), a collection of contemporary fiction featuring a not very helpful twopage introduction by Jay Mclnerney. (He didn't want to herniate himself.) But the stories themselves have a quirky bounce, beginning with "On Meeting My 100% Woman One Fine April Morning," by Haruki Murakami, author of the acclaimed novel A Wild Sheep Chase. It's a parable about a boy and a girl who meet cute. You are my 100 percent woman, he says. You are my 100 percent man, says she. But through garbled transmission they never attain true 100 percent love. There's also "Kitchen," by Banana Yoshimoto. It's not a great story, but what a great name! And lest anyone wonder or worry that Japanese writers have given up playing footsies, the narrator of Eimi Yamada's "X-Rated Blanket" confesses that she washes between her toes in case her lover feels like nibbling. "1 wonder if I am the only woman to go as far as perfuming her toes." One pictures Tanizaki's characters springing upright in their coffins, crying, "Beam me up, baby doll!"

There's an intense twilight to Japanese fiction which pearls even the playful sex with a wistful pallor. Considering how crowded and workaholic the country is, its fiction has an almost pre-industrial absence of clatter. Its characters seldom blab. It's sustaining to know that along with the relative unknowns of New Japanese Voices there are also Tanizaki, Kawabata, and Dazai works yet to be translated. One should keep in touch with such illustrious ghosts. It's like getting reports from the Other Side.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now