Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

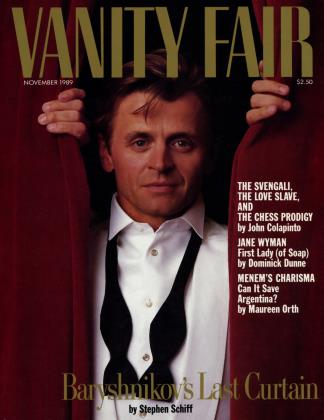

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBELLES LETTRES' BAD BOY

Publishing

You gotta love "Buffalo Bill" Buford, American-born editor of Granta, the star-studded transatlantic literary mag

MICHAEL VERMEULEN

It's eleven in the morning, almost the crack of dawn at Granta's offices above the beauty parlor on Hobson Street, a stroll away from Cambridge University, and Bill Buford is already on the case— manic, hyper in his sotto voce way. The magazine's publisher and another editor have only just arrived I from London. They aren't even out I of their coats yet. "How was the party last night?'' Buford wants to know. "Was it bad that I never made it? Were there writers, ideas around?" They've walked into a fusillade; it sounds like that because Buford is also bashing out a drum solo on the top of a desk.

Granta's weekly editorial meeting begins at 11:30, and then it's Buford's turn to report. He runs through several legal pages' worth of his own comings and goings; the rest of Granta's eight-person editorial staff mostly listen. It's a oneman show, this international publishing event above an English beauty shop, and their job is to keep tabs on him and to keep him in line. "I spoke to Saul Bellow's agent, and he is embarked on a series of shorter works. There may be something there for us," Buford says, his head cradled in his hands, staring down at the table so that all anyone can see is his balding pate and bobbing beard. "I'm getting together with Adam Mars-Jones at nine tonight. I'm supposed to talk with Edmund White at four, but I haven't had time to go through his manuscript yet so... maybe I'll call him after lunch and tell him I'm not going to call him at four. ' ' Thomas Pynchon, V. S. Naipaul, John Updike, Tim O'Brien, John Gregory Dunne, David Lynch, Susan Sontag, Germaine Greer. The whole card-catalogue cocktail party gets spewed out.

Apart from the interoffice intelligence report, the purpose of today's meeting is to get a handle, maybe, on what will be in the twenty-seventh issue of Granta, the closing of which is only three weeks away. Like many editions of the "paperback magazine"—ten years old, with a special commemorative issue on sale this month—Granta 27 will be loosely organized around a theme. This time it's Death. "My crude list of what we should have, which includes a lot of things I haven't read yet...," Buford says, reading aloud a theoretical table of contents. Finished, he announces, "I like that. That's a sort of 'death cluster.' "

Past issues of Granta have coalesced around such diverse topics as science, autobiography, travel writing, the concept of home, and "dirty realism," a badge that Buford, a thirty-five-year-old American, coined and made stick on the allied work of his fellow countrymen Richard Ford, Tobias Wolff, Jayne Anne Phillips, and the late Raymond Carver. Granta has also published new writing by Milan Kundera, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Salman Rushdie, Nadine Gordimer, Martin Amis, the late Bruce Chatwin, and it has introduced a scrum of gifted British journalists: James Fenton, the poet and foreign correspondent who cheerfully looted two presidential palaces in the course of covering revolutionary victories in Saigon and Manila for Granta; Redmond O'Hanlon, the mad jungle explorer and Oxford savage who has taken Granta readers into the heart of Borneo and up the Amazon to cannibal country; and Richard Rayner, whose comic romp Los Angeles Without a Map got its start as a piece in Granta.

It's a real stew—but it works, and has inspired several similarly formatted, if less successful, imitators. If there is a formula to Granta, it comprises three things: non-pedantic political journalism of New Yorker length but proletarian view; travel and intimate reportage that stretches the confines of regular reporting through the depth of its observation and its literary tone; and fiction, like that of Amis and Kundera, which speaks in a strong individual voice, straddles politics, and carries international glamour. This season, Buford also begins the imprint Granta Books, furthering his causes and filling his plate.

A hybrid distribution scheme already sells Granta as a Penguin book in U.S. and U.K. stores, as well as through U.S. and U.K. mail subscription. The last official count put circulation at over 130,000 copies. Of this, 75,000 are taken by American subscribers and another 10,000 sell, issue by issue, through American bookshops. (By comparison, the circulations of The Quarterly and Grand Street are 10,000 and 5,000, respectively.) More impressive still, Granta's American sales have shown something like a 1,400 percent growth over the last three years—a marketing miracle attained through a three-millionpiece direct-mail campaign funded by Rea Hederman, the wealthy Mississippian who owns The New York Review of Books and has been Buford's partner since late 1986.

"I think, in the U.S. alone, it's possible to get circulation up to 150,000," Hederman says in his cluttered Fiftyseventh Street office. Hederman currently owns a quarter of Granta's U.S. operation and a hefty mortgage over the rest. By all accounts, he leaves Buford alone editorially, as he apparently does Bob Silvers and Barbara Epstein at N.Y.R.B. "The main thing we do," Hederman explains, "is we've taken over the business end of Granta, we're trying to improve the subscription base in the U.S., and," he sighs, "we also try to get it published quarterly."

The fiscal year that ended March 30, 1989, was the first one in near memory in which Granta managed to get all four of its promised issues out. That's why Granta is planning issue twenty-seven and its tenth-anniversary festivities at the same time. As a book distributor, Penguin has been frustrated (but indulgent) for years with Buford's readiness to delay publication for weeks and sometimes months in order to "get it perfect." But now, with 110,000 subscribers who have already bought the magazine and expect it in their mailbox, that's not so easy to forgive.

Martha Gellhom, the expatriate writer and a Granta favorite, says, "Lots of people have Bill Buford stories. The angry people have the best." Hers is this: "He did something absolutely terrible to me, and everyone thought I'd never forgive him. He simply stole something from my book The View from the Ground, which was being published in America. He claims he asked me. But when I do business I expect a letter or something. He just pinched a part of the book and put it in the magazine. I seriously thought of killing him, but I was too busy." So she sued? "Don't be ridiculous! I called him a monster, a creep, and told everyone I'd never speak to him again. Then came the big bouquet of flowers and the abject letter of apology, full of lies of course. And I was back talking to him within three weeks."

Amanda "Binky" Urban, the ICM agent who represents Richard Ford, Tobias Wolff, Jay Mclnemey, and a number of other Buford Boys, says that "dealing with Bill Buford is like Brigadoon: you nail it all down and hang up the phone—and everything disappears into the mist. The truth is I despised him for so long. He made me crazy. He can be cheap. He was so difficult to work with. But he liked good writers. My writers. And he has that talent for worming his way into your heart."

Members of the Granta staff describe Buford as "endearing but insufferable." They complain collegially that they sometimes have to stand over his desk and scream to get him to start reading manuscripts. Chris Calhoun, whom Buford brought over to Cambridge from New York to become Granta's advertising manager and who got tossed out of the country within months because Buford neglected to file any immigration papers for him, also retains a certain regard for his old boss. "He's a great salesman. He'll go on and on about how great everything's going to be and then, five minutes later, when you're out of the room, he's forgotten about it all. It's remarkable. It's like nailing jelly to a piece of wood."

"I am singular in the regularity of my apologies," says the editor known around London as "Buffalo Bill." "I am the Great Apologist. Maybe it's that I have no guilt. Or that I have no morality. That must be it!" The saving grace to all this, he argues, is that it's committed on behalf of what goes inside the magazine. "I do fuck up. I forget to write letters. If the magazines have been late, it's because I don't let them go. When I've let magazines go early, it depresses me."

The time that Buford saves not doing things goes into some of the most intense editing sessions to be found anywhere in publishing. The stories of Buford the Line Editor are almost as extravagant as those of Buford the Social Errant. Martin Amis recalled receiving a nine-page letter recommending and defending a number of extremely subtle changes in a nine-page story. Richard Ford once received an eight-pager concerning only a few sentences in his text. Buford has spent three hours on the phone to South Africa arguing with Nadine Gordimer over six adjectives.

Buford guesses he spends between twenty and forty hours working with every manuscript. Usually this occurs in the final three weeks before an issue goes to the printer. The pressures of this schedule do not appeal to every writer, nor do the last-minute liberties that Buford is wont to take with their texts. Some literary big guns now staunchly refuse ever to work with Buford again, yet Granta persists with its editorial gauntlet. In many instances Buford will visit writers at home for wildly lubricated all-night sessions. Or he will fish them up to Cambridge and set them down in the Granta offices for a couple of days, with similar sessions after hours. "There have been pieces that have appeared in Granta in which barely a sentence is the same as in the original," says Richard Rayner, who worked briefly as an editor there. One writer put through the shredder, Nicholas Shakespeare, says Buford canceled fourteen consecutive meetings with him, then sent him a rewritten version the day before the magazine was to go to press. When he protested, Buford delayed the issue for two days to go through the changes. "In the end, I would not quarrel with the text," Shakespeare confesses. "It was vastly improved. But I do quarrel with the way he arrived at that text."

However, there is probably no one around who is quicker than Buford to identify current literary trends. Granta is the chief propagandist for the rebirth of literary travel writing; it brought out the first of its three Travel issues in 1984, and it has been reprinted eleven times. Similarly, Buford's identification and support of his American "dirty realists" have expanded their readership on both sides of the Atlantic. He has also had a hand in popularizing many writers with Eastern-bloc and Third World origins— Salman Rushdie, Ryszard Kapuscinski, Hanif Kureishi, and the late Shiva Naipaul, to name a few.

While it is hard to conceive of the terms "literary magazine" and "power" being used in the same sentence, Buford seems to enjoy possession of both. The writers he showcases often win more generous book contracts because of the 130,000 readers already familiar with their work through the magazine. For this reason, Buford began the Granta book imprint in an international joint venture with Penguin. "Probably the main reason we're doing it is nothing particularly ennobling," he explains. "It really comes down to getting pissed off watching others have fun publishing stuff that we got started." Meanwhile, time ticks by on another Buford project, Among the Thugs, his much-discussed book on English soccer hooligans, originally scheduled for publication in September. "I don't think I've got writing problems," says Buford of his apparent block. "I don't think I've got story problems. I've got time problems."

For a man whose firm tastes and judgments have taken him so far, Buford goes all wobbly when discussing his personal ambitions. He still owns a lot of Granta, so he may someday be rich. But he doesn't ever suggest that money is what he's after. "What I want out of it," he says, "is for the stuff to be.. .well, with Granta Books, my idea is to do perfect books. And to run a perfect magazine. And then to do my own book, and hopefully make that perfect too.

"I never saw myself as wanting to be in publishing," he says. "Published, maybe. But not developing a career in publishing. And that's what made me able to do what I wanted to do in publishing. The only complication has been trying to make it work."

"The point is," says a friend, "Bill Buford is very good news. He stands for good writing and he demands it. You gotta love him. And so you always forgive him. But you always forgive him one inch less."

Bill Buford was bom in Baton Rouge in 1954. Soon thereafter his family moved to Texas, then to Ohio, and finally to California, where Bill and his younger sister did their growing up, in the San Fernando Valley. His father, who is also named Bill, was a nuclear physicist. In high school, Buford was a gregarious B.M.O.C.; he was captain of the varsity football team and he dated a few cheerleaders. He was elected student-body president out of what was then the nation's largest graduating class west of the Mississippi, but he was also something of a cutup. His sister says, "He would do really crazy things. Like when there was a dance and the band took a break, he'd take the microphone and do one of his famous belches that would last a very long time." When their parents divorced, Bill was sent to live with his father and his father's new wife. "As far as my stepmother was concerned," his sister says, "he was a real intrusion. There was a lot of resentment there. Thinking back on it, I don't think he felt very wanted at home. ' '

Buford briefly attended the University of California at Irvine, then transferred to Berkeley, paying his own way. He liked Nietzsche and Camus and wanted to become a writer, but he also showed the makings of a first-rate academic. In 1978, at the end of college, he won a Marshall Scholarship that took him to Cambridge and installed him for two years at King's College. At the beginning of his second year, fellow Kingsman Peter de Bolla bought Buford four or five pints down at the pub and enlisted him to help out on Granta, a college literary publication with an august history and an empty bank account. Founded in 1889 and named for a tributary to the Cam River, Granta had published E. M. Forster and A. A. Milne; David Frost was once its editor; Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath both had early work in its pages. But when Buford and de Bolla took it on, the magazine had diminished to barely thirty-two mimeographed pages.

"Bill decided to solicit work from all these famous American writers," recalls de Bolla. "So he sent them a letter essentially flattering them and intimating, fairly directly, that we were going to organize the whole issue around their work. Only he sent the same letter to everyone, about twenty-five people. He said we were going to have Cambridge critics writing full-length appreciations of them, that sort of thing. It was sort of fraudulent." Six weeks later manuscripts started arriving from William Gass, John Hawkes, Donald Barthelme, Susan Sontag, and others. In the end, it was the volume of material Buford received, not any prescient publishing insight, which dictated the paperback format. Eight hundred copies were printed, paid for by ads from pizza parlors, and it sold out in ten days. Some of the writers weren't too thrilled, though, when the 212-page issue came out and they were included as just one of many. "I still don't think William Gass is very friendly toward us," de Bolla says.

"You always forgive Buford," says a friend. "But you always forgive him one inch less."

Granta 2 came out a few months later. "I was living with a Welsh girlfriend and I didn't want to go back to America and I didn't know exactly what I did want to do." His two-year Marshall funds ran out at about the same time he published Granta 3, but by then he'd caught the bug. In time, the Welsh girlfriend left, but Buford stayed with Granta, taking it off-campus and assembling it in his living room.

Granta's reputation grew slowly while its editor eked out a living with freelance journalism and loans from his mother and the wealthy sporting-goods distributor whom she had married. Buford assumed official ownership of the magazine for practically nothing in 1982, when he and de Bolla formed a shell company and sold themselves the magazine's debts, chattels, and name. "We were cowboys, I guess," says de Bolla, who has since sold his interest to Buford but still sits on Granta's U.K. board. "We just took it over."

The magazine was then selling 10,000 to 15,000 copies per issue. Mindful that the New American Review, the most popular American literary quarterly of the sixties, had been issued and distributed by book-publishing houses, Buford went hunting for a similar deal in 1983. After a little bluster between them, Penguin agreed to print, distribute, and sell Granta and to pay it back a 7 percent "author's royalty" fee. The association with Penguin began with Granta 7. Granta 8 was its first Dirty Realism issue, Granta 10 its first Travel number. Even with Penguin on board, however, money remained an acute problem. Buford met Hederman shortly after he had taken over N.Y.R.B. in 1985, but it took a year for Buford to persuade him to bankroll Granta. According to Hederman, new investment in the magazine will approach $2 million over a five-year period ending in 1991. In addition to subsidizing Granta's large subscription drive, the injected funds have also beefed up the staff and budget significantly.

For all its popularity, Granta is still far from profitable. This, de Bolla explains, "means that as the cost of originating and improving the magazine keeps going up, Hederman is left with a very simple option: he either puts in more money in the form of the debts he pays and thus continues to have a product to sell through his direct-mail campaign, or he pulls the plug." For now, Hederman seems impatient with little except Granta's erratic publishing schedule. Meanwhile, Buford certainly isn't slowing down.

''Bill is a much larger-than-life character than even he lets on," says Richard Rayner. Redmond O'Hanlon delights in telling stories of Buford's fistfights in restaurants, of their trips abroad during which Buford's previous-night passing fancies are wont to leave notes of thanks under his bed. "There is no greater party animal," states this naturalist. Says a past employee, "Bill has cultivated a bad-boy image. He's a little like Billy Martin. He's very childlike.... I think the thing he wants more than anything else in the world is to be forgiven. He's one of these characters that will fuck up almost deliberately, just so he can say he's sorry and win you back again."

It's six o'clock on Monday night and, after a furious weekend of last-minute editing and pasteup, Granta 27 has just gone to the printers. Its publisher, Alice Rose George, who was installed by Hederman, is feeling proud of herself because Granta 27 is the second issue under her tenure to get out on time. Over in a comer, Bill Buford slugs back a three-shot mouthful from a bottle of single-malt scotch. Then he takes the bottle and retreats to his office. The issue may be closed, but his work has just begun.

Stabbing at the buttons on his phone, he races through the stack of messages accumulated during the last week, while he was underwater. "David? Bill. I'm sorry we had an unpleasant exchange before. .." "Christie, this is Bill. I'm at the office now and at home later. I'll be up late. Very late. Call me." One call comes in as another goes out. "Hi! It's Bill. Can you hold on a sec?.. .Hello? Bill. Oh, hi. Hold on, O.K.?.. .Hi, I'm back. What's up? Oh, right, I called you. That means—hold on...Hello? Shit. Gone.. .Hello, it's me.

"Bob? Hi, Bill. Hey, I still don't know what my schedule is for next week. I don't know anything about it at all. But I think I'm going to New York at the beginning of the week and back to Cambridge on Thursday. Short trip. Just to say hello to Rea and check out the office." He pauses for another swig from his bottle. "Anyway, let's leave that thing for the week after next, O.K.? Yeah, I know what I said. But the window just closed. Let's chat then, all right, Bob? Bob? Bob, no. Bob.. .I'm sorry. I mean it. Really. O.K.? Byeee."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now