Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

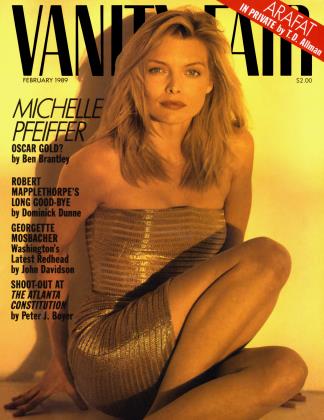

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMichelle Pfeiffer is as golden as the Oscar she deserves for three of the past year's best performances. Under her sunny Californian surface are depths that show up only on-screen. BEN BRANTLEY reports

February 1989 Ben Brantley Herb Ritts Marina SchianoMichelle Pfeiffer is as golden as the Oscar she deserves for three of the past year's best performances. Under her sunny Californian surface are depths that show up only on-screen. BEN BRANTLEY reports

February 1989 Ben Brantley Herb Ritts Marina Schiano View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now