Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDegas's Ladies of the Night

JOHN RICHARDSON

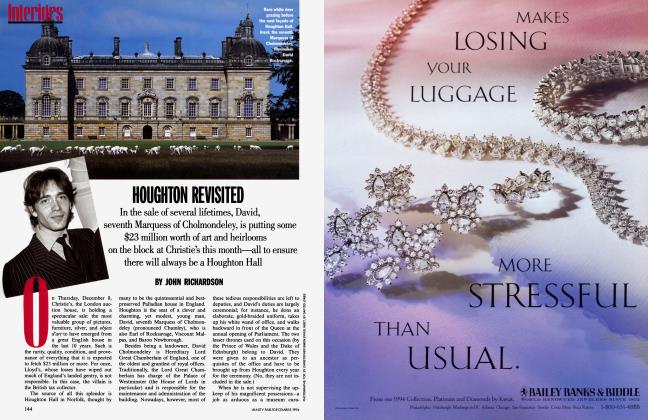

It wasn't all pretty little ballet girls. Degas's dark side was expressed in his monotypes of Parisian brothel scenes. JOHN RICHARDSON explores a lesser-known facet of the great Impressionist, who is the subject of a big fall show at New York's Metropolitan Museum

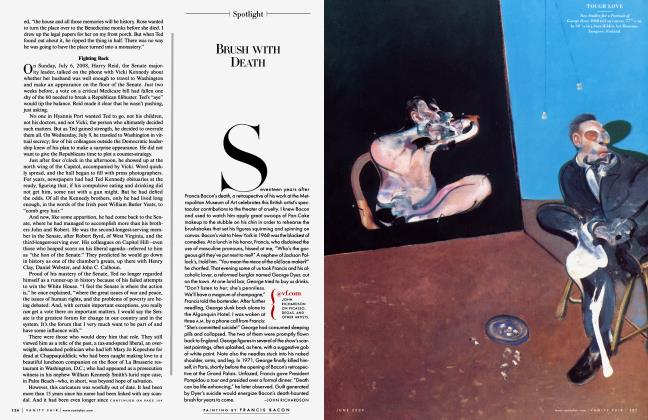

Far and away the best things Degas ever did," Picasso said as he snapped up all the artist's monotypes he could find. But only the whorehouse scenes. He couldn't be bothered with the little ballet dancers fluttering past the footlights in a haze of gauze, or the enchanting landscapes—"too artistic, too abstract!" Picasso eventually ended up with eleven of the brothel ones, which he would proudly show to friends. The immediacy of a snapshot, he would say, yet powerful as a Goya.

The immediacy is inherent in their technique. Given access to a press, all an artist needs is a metal plate, some greasy printer's ink, a rag, a brush, and his fingers. Degas would block in a scene with a few strokes of his brush; model with his fingers (hence all the fingerprints); and blot, smear, or correct with a rag. The only drawback: by limiting the artist to one, at most a second, impression, the process rules out an edition. Hence the term monotype. Colored effects can be achieved if oil paint is used instead of ink. If he wanted color, however, Degas preferred to go over the monotype with pastel or gouache, sometimes obliterating the original ink. These embellishments are often an improvement, but when carried to excess they overegg the pudding. The point of monotypes is that they enable the artist to make prints that preserve the spontaneity of a sketch. Perfect for intimate glimpses of modem life, like the whorehouse vignettes, that depend on lightness of touch and the instantaneousness of a photograph.

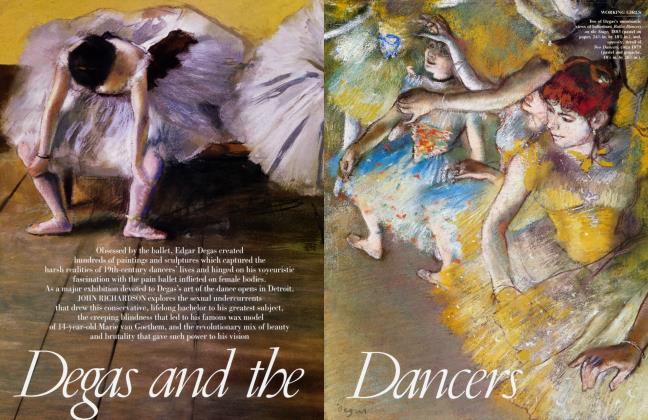

Unlike Toulouse-Lautrec, who portrayed the more lavish brothels of the day, Degas shows us very ordinary maisons closes and spectacles that are the reverse of erotic. Far from being young and appetizing, Degas's whores are oldtimers—potbellied, dog-faced, duckbottomed, like the woman Edmond de Goncourt described as having ''a rhomboidal torso fitted with two little arms and two little legs, which, in bed, made her look like a crab on its back."

The ballet dancers, who inspired another set of monotypes, are younger but often as homely as the whores, whom they resemble, with their black velvet chokers and bangs frizzed over foreheads of simian brevity—"monkeys," Goncourt said when he first saw them. Not that Degas was especially interested in the fronts of his models; he chose them as much for their shoulder blades as their breasts. Just as dancers are portrayed in balletic positions that show off their backs, whores are portrayed in positions associated with their work— squatting on the bidet, bending over to "moon" a client—positions that appealed to the artist's dorsal fixation. Articulated backs are as much a feature of the whores and ballet dancers as they are of the artist's other favorite subject, horses. To believe one of his friends, Degas would inspect a potential model just as if she were a little horse: "Quite fresh and pretty," he would say, "a real find. With a first-rate back. Come now, show your back." For Degas, women who were not, like himself, of the grande bourgeoisie were animals. "It's the human animal taking care of its body," he told George Moore in front of one of his bathers, "a female cat licking herself." The problem was to pin down this human animal in some attitude or movement that would be redolent of everyday life and not smack of the studio.

He evoked an atmosphere heavy with ennui, stale sex, and cigar smoke.

The artistic act become a substitute for the sexual one.

Degas's detached attitude to his models was a constant source of puzzlement to his contemporaries. Confronted with a whore, he betrays no sign of compassion or desire or, for that matter, misogyny (though misogynist he undoubtedly was); no sign of the salacious voyeurism that is such a feature of Picasso's variations on these brothel scenes made almost a century later; no sign, either, of the humanity and empathy that inform Toulouse-Lautrec's paintings of prostitutes.

Degas's monotypes have the modernity of a documentary. The distance he establishes between himself and his subjects, the oblique angles of vision, the daring cropping of figures, remind us that while executing the monotypes Degas was also experimenting with a camera, just as his arbitrary flattening of space and compositional stylizations remind us that he was an assiduous collector of Japanese prints. But it is above all thanks to his incomparable mastery of drawing that Degas was able to conjure up out of a few brushstrokes, inky

smears, and smudged fingerprints complex scenes involving several Figures, mirror reflections, and hints of offstage shenanigans, while at the same time evoking an atmosphere heavy with ennui, stale sex, and cigar smoke.

In many of the monotypes the whores are portrayed under the none too kindly light of a gasolier, sitting around waiting for clients. They look bored rather than coquettish. When a client finally appears, one of them does her best to pull in her stomach and stick out her breasts (a mannerism that Picasso had no hesitation in borrowing), but it is an empty gesture. Apart from a couple of lesbian romps—one of a black girl fondling a white girl—and a scene of a client being serviced in front of a mirror, these monotypes do not depict sexual acts. But this is not because the artist was squeamish. Some 70 of the 150 or so monotypes found in the studio after his death were destroyed by his brother, Rene de Gas, who was in charge of Degas's estate; Eugenia Parry Janis, the leading authority on the subject, believes that many of these were "much closer to pornography" than the ones we know.

If more of the monotypes had survived, we might be less puzzled by the contradiction between the artist's apparent sexlessness and his obsession with women as subjects. Odd, in the circumstances, that Degas never showed the least interest in marriage or even affairs. (His only recorded "mistress" grumbled that he was unable to perform in bed.) Was his condition the consequence, as Picasso suggested, of gouts vicieux or homosexuality? Did all the libido go into the art and leave nothing for the ladies? Was he a Peeping Tom who preferred to watch rather than perform? Or was he, as Roy McMullen, a recent biographer, thinks, simply impotent?

Impotence is probably the answer. Degas's endless nudes were surely a way of compensating for this failing: the artistic act became a substitute for the sexual one—compensation for the fact that he had difficulty getting an erection. "He is not capable of loving a woman," Manet told Berthe Morisot, "or of doing anything about it." And in Goncourt's merciless diaries we read about a model who complained that "he spent four hours of the sitting doing nothing but combing my hair." This was probably as Continued from page 134

Continued on page 178

Degas's Ladies of the Night

near as Degas came to making love. Unlike most of his fellow artists, he was famous—some would say notorious—for treating models with scrupulous formality.

As well as having sexual problems, Degas suffered from deficient vision. His myopia had been severe enough to excuse him from military service, and by 1873, when he was nearly forty, the deterioration in his sight was plunging him into ever greater bitterness and gloom. He had virtually lost the use of his right eye, and this inevitably put a terrible strain on the left one. By the nineties, blacked-out spectacles would cover both eyes except for a small slit in the left lens; little by little he would be obliged to abandon painting for pastel, pastel for sculpture, and, by 1912, give up work altogether. But far from deteriorating, his work never faltered, as is apparent from the sharp focus and tonal accuracy of the monotypes.

On top of all these physical problems, Degas experienced severe financial reverses at the time (the mid-1870s) he was working on the brothel scenes. Although raised in far more comfortable—not to say luxurious—circumstances than petit bourgeois confreres like Monet and Renoir, Degas was suddenly faced with the specter of ruin. In 1876 the family bank that had enabled him to work in comfort collapsed. Worse, the artist's brother Rene, who lived in New Orleans, where their maternal family, the Mussons, dealt in cotton and Mexican silver, not only reneged on a large debt

but left his wife, who was blind, and six children (four of whom proceeded to die) for another woman. Although he refused for many years to receive his caddish brother, Degas agreed out of family pride to help pay off the debt in monthly installments. This crippled him, and for the first time in his life he was obliged to make money from his painting. The monotypes were done to sell; they failed to do so.

The setback transformed Degas, formerly as progressive in politics as in art, into a bigot. The nastiest manifestation of this was his anti-Semitism: a malaise that Degas shared with Cezanne, Rodin, and Renoir (who once said of an old and dear friend, "To exhibit with the Jew, Pissarro, means revolution"). Degas was even more of a fanatic. When one of his models expressed doubts as to Dreyfus's guilt, he screamed, "You are Jewish...You are Jewish" (which she wasn't), and threw her out of the studio.

In a shrewd analysis, "Degas and the Dreyfus Affair," Linda Nochlin explains why this "brilliant innovator, and one of the most important figures in the artistic vanguard," abandoned his once pro-Jewish attitudes for rabid anti-Semitism. One of Degas's closest friends and the subject of many of his portraits was an attractive and distinguished Jew, Ludovic Halevy, an haul fonctionnaire who dabbled in literature and is principally remembered for co-authoring the libretto of Carmen for his cousin Georges Bizet. So attached was Degas to the Halevys that he kept two large sketchbooks in their house and

would fill them with drawings in the course of his visits. The two friends worked together on photographs that Mme. Halevy would develop. But even more of a link than photography was the ballet. While Degas would draw the petits rats in the coulisses and rehearsal rooms of the Opera, Halevy would make notes for his satirical' stories about backstage life—stories about two dancers, Pauline and Virginie Cardinal, their boyfriends, and their impossibly possessive mother. When these were to be published under the title of La Famille Cardinal, Degas agreed to illustrate them with a series of monotypes.

Alas, the pressures of misfortune had tinged the artist's sense of irony with spite, and he could not resist compromising the respectable Halevy by depicting him very recognizably as the narrator: "too much a part [Nochlin says] of the rather louche business of selling young women's bodies behind the scenes at the Opera." Halevy might also have spotted himself, Nochlin thinks, as one of the tophatted clients in the brothel scenes. The upshot was that the author turned down the monotypes: they were "too idiosyncratic," he said. The friendship would never be quite as trusting again. And when, as a result of the Dreyfus case, Degas's latent anti-Semitism burst into hideous flame, the poor Halevys were appalled to find themselves cut out of their old friend's life: "One last time Degas dined with us," the son, Daniel, reported. "[He] remained silent...not a word came from those closed lips, and at the end of dinner Degas disappeared." Henceforth he confined his friendship to people who shared his fanaticism or did not find fault with it.

Did Degas's ghastly views have any effect on his art? Not directly. It would be difficult to revere him as much as we do if they had. But this is something that every visitor to the great Degas retrospective that comes this fall to New York's Metropolitan Museum via the Grand Palais in Paris must decide for himself. I confess that as I left this dazzlingly beautiful show, I was conscious of something missing: the physicality we find in Titian

or Rubens, Ingres or Renoir. Degas was like a great chef without a sense of taste. It is tempting to diagnose his sexlessness as symptomatic of misogyny, but that would be a mistake. If his whores are often piglike, it is not because he despised them. It is because he was out to redress the kitschy chocolate-box image of Second Empire womanhood. In the brothel scenes, Degas does not preach or titillate or rub our noses in squalor. The lowest life has been distilled into the highest, sparest, most dispassionate art. Therein lies the greatness, the coolness, and in the last resort the coldness of these works.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now