Sign In to Your Account

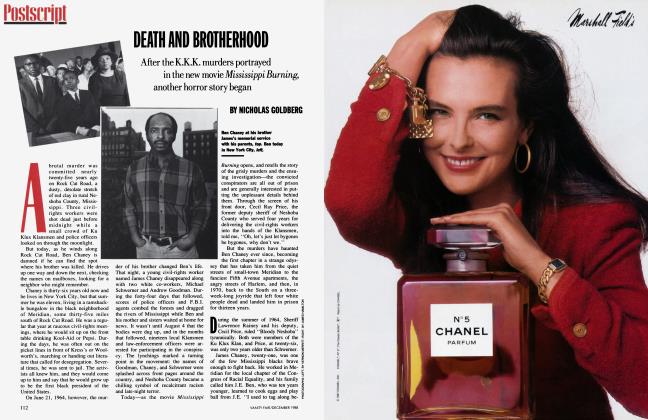

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWho Killed Libby Zion?

Since his teenage daughter checked into New York Hospital with a fever and died mysteriously, Sidney Zion has created a media blitz, accusing doctors of killing her. Now, after seven thousand pages of new testimony, M. A. FARBER pieces together what really happened that night—and finds that the story of Libby Zion is very different from the one her grief-stricken father portrays

It was on a cold February night, "right near the end," as the writer Sidney Zion recalls it, that he and his eighteen-year-old daughter, Libby, a Bennington College freshman, were walking down Fifth Avenue and she said she was going to be famous one day.

"Nobody says you have to be famous," Zion told her.

"But I'm going to be."

"And I said, 'What are you going to do?' "

'Well, I'm going to be a singer.' "

" 'Can you try something a little easier?' I said."

"And she said, 'Well, maybe I will be a journalist. How is that for easier?' " Libby Zion did become famous, and because of what she became famous for, Dr. Luise Weinstein sits staring at the floor in a barren, windowless hearing room at the midtown-Manhattan offices of the New York State Health Department's Office of Professional Medical Conduct. It has been more than four and a half years since Libby Zion died at New York Hospital, and in the next weeks the first quasi-judicial judgment will be rendered on Dr. Weinstein, the intern who treated Libby and who is accused of gross negligence and/or incompetence. This is the doctor whom Sidney Zion has publicly called a murderer, who, along with other physicians, "executed" his daughter in the early-morning hours of March 5, 1984, "abandoned" her, "let her die there like a dog and worse than a dog."

What Libby Zion became famous for was dying, and the events surrounding her death—from the moment near midnight when she stepped into the emergency room to the moment upstairs nearly seven hours later when alarms went off and doctors came running and the resuscitation machines were thrown into motion and the nurses started crying and Libby slipped away—have been laden with controversy from the outset.

The issue before the Health Department panel hearing the arguments in the Zion case is not why Libby died, but whether the doctors' actions were in accord with generally accepted medical standards. Nonetheless, the cause of her death has been the leitmotif of the hearings and will be a key element in Sidney Zion's suit against the hospital, which is to go to trial in Manhattan Supreme Court. In many ways, the hearings have been a dry run for that trial. But, after thousands of pages of testimony, no one yet knows why Libby Zion died, and, strikingly, there is no hard evidence to support the claim by her father and the state that a drug improperly administered by the doctors was fatal. The hearings have made plain that the illness and death of this young woman, like the treatment she received at New York Hospital, is a far more complex story than has been portrayed publicly.

In postmortem analyses, there was no confirmation of cocaine in Libby's body.

This is not just a story of how medicine is practiced at the best places. It is also, it now appears, a mystery story in which, sadly but surely, there is more than one victim.

lump and red-haired, Libby Zion was a generous and reflective, if insecure, young woman—an imaginative, versatile writer, an enthusiastic, if erratic, student of music and literature and history —who, like so many teenagers, was uncertain of her direction in life. She had had more than her share of anxiety and medical problems long before she arrived at New York Hospital. Many of her friends, and some of her classmates at a private school on Manhattan's Upper East Side, were privileged and sophisticated, but youngsters to whom a broken home or a troubled life was not foreign. Two of her closest friends overdosed on pills, and the brother of her last boyfriend, who could build a bike from scraps and play almost anything on the guitar but who was also a drug abuser, died from a combination of heroin, cocaine, and Quaaludes.

To some of her friends, Libby Zion seemed a throwback to the sixties: from her funky bedroom with its peacock feathers to her baggy clothes—partly an effort to minimize her wide hips—to her concern about the environment and nuclear weapons. They remember her as "a decent human being, willing to give of herself and do the right thing." She was also ''high-strung emotionally, and if you got on the wrong side of her she could be vengeful," said a friend who recalled cutting classes and taking drugs and listening to rock music with Libby and others in their group. ''But, to us, she was very kind and very nice. And she had such high integrity, especially about the information the public gets. She would have been offended about the amount of untruth about her now."

What happened to Libby Zion the night she died—or what did not happen but perhaps should have—rocked one of the world's great teaching hospitals, costing it hundreds of thousands of dollars in lawyers' fees and probably much more in lost prestige, staff morale, and unoccupied beds. New York Hospital, founded by royal charter on the eve of the American Revolution and for generations a preferred hospital for many who could afford treatment anywhere, was enveloped in bad publicity after Libby's death. Then, in February 1987, Andy Warhol died unexpectedly following gallbladder surgery at the hospital, setting loose a new wave of criticism, in which, again, the state Health Department joined. Warhol's estate claims, in a suit still in its early stages, that the artist did not receive proper medical or nursing care; the hospital says that, with some lapses, he did.

It is impossible to accurately measure the damage done to New York Hospital by the deaths of Warhol and Libby Zion. Although it has been under new leadership since mid-1987 and continues to admit more than 40,000 patients a year, it is millions of dollars in the red—partly because of changed reimbursement formulas for patient costs that have affected other medical centers as well. But, unlike its biggest competitors, whose patient-mortality rates are for the most part no better, New York Hospital now also has to contend with a lingering, perhaps even a popular, notion that, somehow, it is not a safe place.

For Sidney Zion, these have been four and a half grueling years, years in which his rage, sorrow, and determination not only delivered a body blow to New York Hospital but provided an impetus for reforms that will soon affect hospitals throughout New York State and perhaps, eventually, the nation.

It was in character for Sidney Zion not to let go. Yale Law School grad, former federal prosecutor, muckraking newspaperman and civil libertarian, Broadway restaurateur, Boswell to Roy Cohn—Zion is a big, glib, gutsy New York fixture who can count as many friends, and in high places, as Luise Weinstein could count patients. When he vowed that Libby's death would not be forgotten, it was a sure thing it would not be.

For Luise Weinstein, too, these years have been a nightmare made real, a wasted passage in a brilliant career. What has happened to her since that moment when no one could awaken Libby Zion is unlike anything she had been prepared for. Weinstein, now thirty-one years old, is not one of those doctors who abuse or sell drugs or assault patients or have been so poorly trained as not to deserve a license in the first place. She is smart, if dry; articulate, if reserved; and, by all accounts except that of Sidney Zion, who called her an "affirmative-action woman doctor who had the soul of a yuppie," so devoted to her profession, so compulsive and careful about her work, that she has barely any other life. Aside from the charges lodged against her in the Zion case, her record is unblemished. At New York Hospital, doctors tell of her having saved lives through sheer skill and diligence, of her "quiet dignity" and "humanity." A product of Brooklyn's middle class, Weinstein is the classic academic overachiever—a summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa graduate of the University of Rochester in 1978 who, after a year as a methods analyst in New York, enrolled in the medical school at Rochester. New York Hospital, an affiliate of the Cornell University Medical College, was her first choice for training as an intern. The hospital was happy to get her.

Today, instead of the distinguished research fellowships that were within her grasp, Luise Weinstein holds what a senior physician describes as a "second-class" clinic job. "When you see her around the hospital, it's like seeing a person who's lost half her face." Others routinely portray Dr. Weinstein as destroyed, finished nearly at the start— not quite in jail, as Sidney Zion wanted, but caged by embarrassment and fear.

For nineteen months Luise Weinstein and Gregg Stone, a resident who also examined Libby Zion the night she died and who faces roughly the same charges, have been attending the hearings whose outcome will further define their careers. Stone, a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of the University of Michigan in 1978 who was near the top of his class at the Johns Hopkins school of medicine, has borne less of a burden than Dr. Weinstein and, after completing his residency at New York Hospital, was admitted to the cardiology-fellowship training program at Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. Every few weeks, on average, he flies back to his past, at the expense of New York Hospital, and sits impassively in the claustrophobic room on the third floor of 8 East Fortieth Street, a mop of curly brown hair atop an open face adorned by gold-rimmed glasses. His suits are dark; his soft loafers, like his manner, polished. Luise Weinstein sits two places away, looking tortured by the shame of simply being there. She is no more than five feet two, and seems even smaller. Her skin is pale, her hair, raven; her dark-brown eyes, almost always downcast, are set in a narrow face with a prominent nose and receding chin. Her ankles are crossed, her fingers clenched.

In January 1987, a grand jury convened by Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau returned no criminal indictments in the Zion case, but said that Libby "might have survived... if she had received the experienced and professional medical care that should be routinely expected" at an institution like New York Hospital. The grand jury also proposed reforms that included limiting the number of hours that possibly fatigued interns and residents can work consecutively, a rule that will be imposed by the state beginning next July. Never mind that fatigue was never a factor in Luise Weinstein's care of Libby Zion, or that the grand-jury report, which led to the appointment of a special state commission, was based on incomplete information and contained important factual errors. This is also a case in which New York Hospital, without any confirmatory evidence, linked Libby Zion's death to cocaine abuse, a case in which the hospital paid a $13,000 fine and admitted lapses in its procedures mainly— or so administrators say—to ensure that the state would not hold up approval of its building program. And, in the view of many doctors, it is a case driven as much by political maneuvering as by medical propriety. "If Libby Zion had been a bus driver's daughter, we would all have said we were very sorry and meant it and that would have been it," remarked one New York Hospital physician. "But Sidney Zion had the ability to communicate his personal tragedy." As Terrence Sheehan, counsel for the Office of Professional Medical Conduct and, in effect, the prosecutor for the case, put it, Zion is "one of the most aggressive, unshy, forthright, pushy people that you're likely to see. He is not a little wallflower."

So far, the transcript of the Weinstein-Stone hearings exceeds four thousand pages, without supporting exhibits. There is also a more recently initiated but related proceeding in which Dr. Raymond Sherman, an attending physician with supervising and admitting privileges at New York Hospital, is charged with gross negligence for, among other things, failing to come to the hospital to see Libby Zion. The transcript of that proceeding already runs to three thousand pages.

What these documents show is that the case against Luise Weinstein rests on a very fragile foundation. And the testimony of a dozen medical experts called by her attorney, Paul Rooney, has undermined that foundation at every point. Given the battering she has taken in the press, Weinstein is faring very well at these hearings. So is Gregg Stone. The best measure of that was provided a few months ago when, unexpectedly, Terrence Sheehan disclosed that he would not ask the hearing panelists—a retired Staten Island ophthalmologist, a Rochester orthopedic surgeon, and a former medical-college administrator in Albany—to recommend revocation of licenses, but only such lesser penalties as suspension, censure, or reprimand. It was a stunning concession in a proceeding that had begun with Sheehan assailing the defendants' "medical arrogance" and blaming them for treating Libby Zion as if she had a "bad cold" rather than a "life-threatening disease process." But Sheehan had concluded by last June that there was no sense in asking for what the state could not get. Now, near the windup of the Weinstein-Stone hearings, he worries that the state may get nothing.

This is hardly what Sidney Zion had in mind. But as a connoisseur of litigators, he might appreciate how Rooney, the fiftyyear-old defense attorney—a smooth, goateed former federal prosecutor who put Carmine DeSapio behind bars—has overwhelmed Sheehan, who is twelve years his junior, much less amply funded, and in no courtroom sense his match. "I'm trying to learn, I'm only an intern here," Sheehan joked during one session. Despite his decade of trial work for the state Health Department, the gangling, six-foot-three-inch prosecutor has been rebuked time and again in the hearings by members of the panel or by the nonvoting administrative officer who oversees the proceeding. This was especially true during Sheehan's questioning of Luise Weinstein, when he was told to stop "badgering" the witness and to give up lines of inquiry that were "ridiculous." Flustered, Sheehan reminded the panel that the state health commissioner and the Board of Regents are responsible for the final decision on the defendants, and that he needed to "make a record" for the ultimate review. On one occasion, the hearing officer urged the prosecutor to "ask a simple question." "I can't," Sheehan shot back. "It's a complicated case we have here. This is medicine."

What this "complicated case" is all about, of course, is how someone characterized by Sheehan as a "young, otherwise healthy girl" suddenly became a corpse. And the answer to that may have as much to do with who Libby Zion was and how she lived as with what New York Hospital doctors did or did not do in the early-morning hours of March 5, 1984.

The oldest of the three children of Sidney and Elsa Zion, Libby was remembered by her father as "the kid who edited my leads from age eleven or twelve," the kid who when the columns or magazine pieces were right would give him "the Libby smile, the sparkler, the one that turned down slightly at the right corner, the smile that said, 'That's my daddy, sticking it to 'em.' " At Yale, with help from his old pal Frank Sinatra, Zion established a fellowship and lecture series in Libby's memory, and it was there, in a eulogy a year after her death, that he spoke of going to her with his writing because "I trusted her taste and I trusted her honesty. No father could ask for more— though it worried me, and I told her so, that the combination would make it tougher in a world that most often prized neither. Every time I'd pull this long face, Libby would laugh and say, 'Don't worry, Daddy, I can handle it.' It gave her trouble now and then, this taste and honesty. It gave her trouble with teachers here and there, with friends, with boys. The Libby smile would disappear when it happened; she'd storm around the apartment, break some dishes. Once, at Bennington College, she put her hand through a window. But always the laughs brought her back. 'Don't worry, Daddy, I can handle it.' "

But, in truth, a laugh did not always bring Libby back, and there was often a question, even in her own mind, of what she could handle. In 1982, in a letter to a boyfriend whose initials are T.G., she recalled that, as early as the eighth grade, "when I didn't smoke so much pot. . . and I had never done any other drugs either...I was generally considered the smartest girl in the school. That's probably why I went to Fieldston. It's also exactly why I left. Figure it out yourself. ... I'm just a mass of contradictions." From Fieldston, an exclusive school in the Bronx, Libby transferred in the tenth grade to the New Lincoln School in Manhattan. At first, her grades there were average. But they improved significantly in her second year, and, despite a pattern of repeated absences, Libby excelled in her senior year. One English teacher recalled her capacity for "sharp-witted analysis," how she caught "the remote and intangible connections that others miss." There was a "kind of waywardness" in her work owing to her impatience and impetuosity, he said. But she was intuitive and original and increasingly solid. "Libby had problems with her attitude toward school—she would stay home and write or read or watch television—but, for her, the work was effortless," a classmate remembered. "She got through The Magic Mountain when I didn't." Socially, the classmate said, Libby "didn't mix well at school. She was apathetic about school activities and picky about her friends. She would rather be alone than with someone she didn't like."

Libby indicated to her psychiatrist that she was emotionally tormented and physically hobbled by continuing despair.

Off and on, Libby saw T.G., whom, judging from her letters, she alternately loved and rejected, a boy whom she begged to leave her alone—"while I am somewhat astray, you are lost"—and then to whom she wrote tenderly and candidly and moodily about everything from her dreams to her fear of failing physics. "I have managed to contract the flu," she wrote in 1982. "And naturally I ignored the symptoms for 3 days, which inevitably led to my being sick as shit at the present moment. I have a fever of 102, and I've been throwing up for 3 days. But like I said, I ignored all my symptoms. I was an asshole, what can I say? That's part of the reason I'm so cranky—because my mother will be able to say 'Baha, I told you so.' Which of course she did, but we won't mention the fact that I ignored her. I'm really pissed. All weekend long I waited for some coke to come through, and it didn't. How incredibly annoying! Plus it rained all day. . . which made me crankier, and there was no good pot, so I couldn't even get stoned. DRAG!"

T.G., who says that Libby once saved his life after he overdosed on pills in his apartment, remembers her as one of the very few "good" people he has met, a girl who, while she didn't yet know what she wanted from life and was insecure about her looks, really hungered for "recognition. She had a great need to be accepted." Libby's use of cocaine—which she "hid from her parents"—and such drugs as Elavil, an antidepressant, was "just recreational"; she was not addicted, he says. Libby was "more into pot, which we didn't consider a drug."

Libby's parents have said they thought their daughter had only experimented with marijuana or used it sparingly; they knew nothing, they said, about any use of cocaine by her or her friends. Yet if Libby didn't always confide in her parents, her friends say, she and her father—whom she saw a lot of, since he spent much of his time at home writing his columns and books—enjoyed a relationship of mutual love and regard. "They fought a lot—she was like a fiery redhead—but she was her father's precious," recalls a girlfriend who spent many hours in the Zion s' Upper West Side apartment. "Libby respected Sid and was proud of him," says T.G. "But there was a barrier because he was a perfectionist."

(Continued on page 214)

(Continued from page 195)

Libby graduated from New Lincoln in Tune 1983 and enrolled at Bennington, in Vermont, that fall. She quickly developed a dislike for the college, which, she told her mother, had "too many neurotic kids." In early January 1984, as part of a Bennington work-study program, Libby took a $200-a-week internship in the office of her father's friend Andrew Stein, then the Manhattan borough president. Stein, now the president of the New York City Council and Elsa Zion's employer, testified at Luise Weinstein's hearings that Libby was "a delightful young woman," responsible and attentive to her work on day-care issues. "She was very cheerful and a very happy kind of person and very enthusiastic. She had a good disposition."

However happy and adjusted Libby seemed to Stein (who in 1987 wrote an article in the New York Post lambasting the hospital and saying that Libby died of "medical neglect"), she had started to see a psychiatrist around the time she went to work for him. For several years Libby had suffered from irritable-bowel syndrome, an often psychosomatic illness that her mother described as a "chronic pain in the gut." Tests ordered by Raymond Sherman—a respected internist who was more Sidney's doctor than Libby's—did not isolate the source of the pain. To reduce stress on Libby before she returned to college in March 1984, Elsa Zion arranged for her daughter to take an eight-session course in January and February in biofeedback techniques for controlling abdominal pain through breathing exercises. It was given by Kenneth Greenspan, a psychiatrist. Occasionally, Sidney Zion went with Libby and, in another room, availed himself of the program. In late January 1984, after unsuccessfully trying an antidepressant called Tofranil, Dr. Greenspan put Libby on another antidepressant, Nardil. According to Sidney and Elsa Zion, she never complained of depression, and they had not observed it. But Libby, they testified, told them that Greenspan, with whom Libby had developed "a more expansive relationship," felt she needed the Nardil to correct a chemical imbalance. Sidney and Elsa said they never learned more about Libby's conversations with Dr. Greenspan.

In fact, Libby had indicated to Greenspan that she was emotionally tormented and physically hobbled by continuing despair, from which marijuana provided some refuge. During the Sherman hearings earlier this year, Sidney Zion depicted his daughter as "an active, healthy kid," a young woman who had "little problems here and there, colds, other things of that nature," not "some kind of half-invalid kid who was sick all the time. Perfectly normal? I don't know what the word normal even means. . . . Everybody's kids get sick once in a while. That's the way it was, and nothing special." Sidney said he now understood that whatever depression Libby was suffering stemmed from her stomach pain: "It wasn't a psychiatric problem." Greenspan was "talking to her, not analyzing her, just talking to her and he gave her this antidepressant. I didn't know she was depressed, to tell you the truth. She was always smiling around me. But she was an eighteen-yearold kid and maybe she was depressed. He gave her this, and I never really questioned him. I trusted him, as I trusted Dr. Sherman. I trusted the doctors very much and didn't second-guess or ask too many questions, to my dismay."

Although Sidney and Elsa Zion were unaware of it, Libby was examined on January 25, 1984, at the Hospital for Special Surgery by Dr. John Lyden, an orthopedic surgeon. She had been referred to Dr. Lyden by Dr. Sherman, who had seen her only twice, in 1981 and 1982, but continued to authorize Valium and Darvocet prescriptions for her until a month before her death. Dr. Sherman kept no records in Libby's office file of the phone conversations that led to those prescriptions, but he testified at his hearings that the drugs, in small amounts, provided "some relief" from tensions associated with her bowel problem. According to Dr. Lyden's testimony at the Weinstein-Stone hearings, Libby said that she had a history of spastic colon and migraine headaches and that now her shoulders ached. Libby, Dr. Lyden said, was "extremely agitated, she couldn't stay in one place in my examining area. She was constantly in motion." She said that she was using Darvon, an analgesic; Robaxin, a muscle relaxant; Indocin, an anti-inflammatory drug; and other medications she would not identify. Lyden, who took X-rays, testified that he could find nothing wrong with her shoulders other than some laxity in her joints. "She was inconsistent. . .and kind of demanding," he said. "Nothing really fit." Libby asked him for pain medication "considerably stronger" than Darvon, Lyden said, and when he refused, "that's when she got upset, and I think the consultation ended soon thereafter." Prescribing only some shoulder-strengthening exercises, Lyden told Libby he would not charge her a fee, on condition that she not return. In a telephone conversation, he said, he advised Dr. Sherman that "as best I understood, the pains were not real and she was looking for narcotics." Sherman testified that he could not recall the details of this conversation, but that Dr. Lyden's written report to him "did not convey to me that this girl was seriously disturbed" or seeking drugs. "This was a family that I was aware of. The father was my patient. The grandmother was my patient. I had interactions with the family, and I would have expected that if anybody saw anything unusual in terms of her behavior that I should know about it."

A few weeks after her visit to Dr. Lyden, and a few weeks before her death, Libby broke up with Edward Ramming, with whom she had had a romance since the summer of their junior year in high school. "They were very devoted to each other," Elsa recalled. "She was very supportive of him, and he, in a way, couldn't do enough for her." But some of Libby's friends, of whom Ramming did not approve, did not like Ramming and urged Libby to dump him. Libby came down from Bennington a number of times in the fall of 1983 to heal matters and, when she was working in New York during the winter, spent many late afternoons and evenings at Ramming's apartment. But they drifted apart.

Three and a half years later Ed Ramming, who was by then studying to be an airline mechanic, became the only one of Libby's friends to appear at the Weinstein-Stone hearings; he was called as a surprise witness by the defense. Ramming swore that Libby and he had snorted cocaine at clubs and friends' houses. But the last time he had seen her use cocaine was in the summer of 1983. Ramming also testified that Libby often took pills for one reason or another. "If she was feeling bad, she would take a pill. If she wanted to go to sleep, she would take a pill. It was a habitual thing." Around the time they broke up, he said, Libby had complained that she was getting sick from an antidepressant.

In late February 1984, Dr. Greenspan, the psychiatrist whom Libby had been seeing, referred her to a dentist, Alan Wasserman, who, on Thursday, March 1, extracted an infected lower left molar, inflamed at its base. Wasserman wrote a prescription for Percodan, a painkiller. That day, Libby also developed an earache and visited her regular doctor, Irene Shapiro. Shapiro, who later told lawyers that she did not detect an infection, prescribed erythromycin, an antibiotic, and Chlor-Trimeton, an over-the-counter antihistamine. The prescriptions for Percodan and erythromycin were filled that afternoon, as was a prescription for Valium from Dr. Greenspan. Libby also picked up a new supply of Nardil. In the evening she spoke to Dr. Wasserman and said the bleeding around her tooth had stopped and she had taken one Percodan. She said that she would phone him if there were problems. Wasserman called her the next morning, Friday, March 2, and, according to what he later told lawyers, she said she was fine. He never talked to her again.

That morning, Libby went to Andrew Stein's office, where some of her coworkers had planned a farewell party. She was due back at Bennington on Monday. But, feeling poorly, she quickly returned home and went to bed. Her mother remembers Libby taking her own temperature and finding it to be 101.

Libby's general discomfort continued on Saturday, March 3, and she was in and out of bed. Elsa recalled that her daughter was still running a fever but "didn't look terribly sick." Ed Ramming, who was in touch with Libby despite their breakup, visited in the afternoon, and found Libby sweaty and hot though not feverish. "She wasn't shaking or flailing her arms or anything," he testified, "but she was restless. She wasn't able to stay in one spot." At one point, he said, Elsa brought Libby a saucer of fifteen or twenty pills that he was told were vitamins. Libby swallowed them a couple at a time.

Around noon on Sunday, March 4, Libby told her mother that she felt as if she was "burning up." Elsa took her temperature, then "about 102," and decided to bring Libby to Dr. Shapiro. But, she testified, Shapiro told her on the phone that the drugs she had prescribed for the earache—the antibiotic erythromycin and the antihistamine—were all she could give and that she was just leaving for a twoweek holiday. She gave Elsa the number of a doctor who would be covering for her. He was never called. On Sunday afternoon, according to her mother, Libby took Tylenol and erythromycin and Elsa administered alcohol rubs and cool towels. Libby tossed around in bed with her "entire body," Elsa remembered. "She was never really still in her bed." Libby's temperature remained at about 102, Elsa said, but by seven P.M. she felt a little better and wanted to sleep. Sidney and Elsa, instructing their son Adam to phone them if there was any problem, left for a dinner party at Park Avenue and Sixty-second Street, ten or fifteen minutes away. They were celebrating a friend's admission to the bar.

Around 9:30 P.M. Adam called his father. "You better get right home," he said. "She really looks terrible." Sidney and Elsa jumped in a cab. At home, they found Libby out of bed and visibly worse than earlier in the day. She was agitated, "like half a Mexican jumping bean," Sidney said in his own deposition. Her eyes were "rolling around, like dilating or whatever you want to call it." Elsa recalled someone taking Libby's temperature, and that it was 103. Sidney phoned Raymond Sherman at his home. Dr. Sherman told him to get Libby to the emergency room at New York Hospital and "we'll see what's up." Meanwhile, he would alert the hospital and get Sidney the name of the emergency resident on duty. Sidney asked Sherman if he would be there. "If they need me," Sherman said, "of course I'll be there." Libby was coherent enough to call a friend at Bennington and say that she was going to the hospital. As Sidney was about to get his car, Libby told him that she was frightened. "Now, you don't have to be scared," her father assured her, "because we are going to the best hospital in the world. We are going to take care of you and you will be great."

Inscribed in marble in the huge foyer of New York Hospital are foot-high letters: AT THE GATE OF THE TEMPLE WHICH IS CALLED BEAUTIFUL. Accompanied by her parents, Libby Zion arrived at this temple of medicine at 11:40 P.M. The first doctor who saw her was a junior resident, Maurice Leonard, who, after graduating from Yale University, had attended the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and graduated with honors. With Elsa comforting Libby in the examination room—Sidney would be more removed throughout his daughter's stay at the hospital—Dr. Leonard conducted a physical and neurological examination, and attempted to take Libby's medical history. He was told about the tooth extraction and the earache; he saw no sign of infection when he looked into Libby's mouth and ears. He recalled during his testimony that Libby said she was taking Nardil for depression and erythromycin for her ear but had felt too sick that day to take either. (Although her mother testified that she had taken the antibiotic and that Leonard was told about this.) Leonard testified that he was not informed about other medications prescribed for Libby since she had come home from college in December. In addition to Percodan, Valium, Chlor-Trimeton, and Tofranil, there were Dalmane, a sleeping pill, and tetracycline and doxycycline, both antibiotics—and possibly the three others she had told Dr. Lyden she was taking in January.

In the emergency room Libby had a rapid pulse and respirations, orthostatic changes in blood pressure that could indicate dehydration, and a temperature of 103.5. She told Dr. Leonard that it had gone as high as 106 that day (which is several points higher than her parents have ever recalled it being). Her chest X-ray was clear. "When she was calm, she was very calm and rational," and she could be calm when asked to be, Leonard testified. "At other times she had a behavior of purposeless movements, moving her arms, her legs, rolling from side to side, sitting up, sitting down." It was, he said, "almost like a light bulb being turned on and off." When Elsa stepped out of the room, he asked Libby about drugs. She denied using cocaine but said she frequently smoked marijuana, although not that day.

Dr. Leonard called Dr. Sherman after the physical examination and again after receiving some test results—including one that showed Libby to have an elevated white-blood-cell count, indicating an inflammatory process. Among the things he mentioned to Sherman was Libby's use of Nardil. "I think that both of us had a hard time putting everything together into one particular so-called neat little package," Leonard told the Weinstein-Stone panel. "It was a little confusing in that she had this behavior that seemed bizarre and also that she had the fever and the muscle aches." Among conditions considered were pneumonia, bacterial meningitis, a urinary or gynecological infection, viral syndrome, and—less likely because of Libby's denials—a drug reaction. The two doctors agreed that Libby should be admitted for further evaluation, but she was ruled out as a candidate for the intensivecare unit. Although Elsa Zion testified that Libby was breathing in a "shallow manner" in the emergency room and, subsequently, in her own room, Dr. Leonard said the patient "had no problems breathing. There was no evidence of any cardiac disease, no arrhythmias. Her blood pressure, although on the lower side of normal, was not in the dangerously low category that required any kind of monitoring or treatment with any drugs that would not be available on the floor." Neither he nor Sherman considered Libby's condition life-threatening.

Dr. Leonard later testified that Dr. Sherman "seemed more concerned than most of the [attending physicians] who call up in the middle of the night" and have their patients taken to the emergency room. Even more concerned, perhaps, was Sidney Zion. Shortly after midnight, he phoned Sherman from the hospital. "I said, 'Ray, my kid is here,' Zion recalled. " 'Why aren't you here? I want you to be here. I don't know who these people are. . .they are saying she's hysterical, and I want you here.' " According to Sidney, Sherman said that Dr. Leonard and others on the staff were "the best people there are" and he was "right on top" of the situation. "Understand something," Sidney remembered Sherman telling him, "if there was anything wrong I would be right there now. Don't be ridiculous." The internist said that Libby probably had a virus which "looks a whole lot worse than it really is" and that he should relax. "Ray talked to me as if I was just a jerky Jewish father who was overreacting to this, and I felt good about it, and I really did feel very relaxed because I knew in my heart without any doubt that if this was anything serious he, who I have known for many years, would have been right there on the spot."

Dr. Sherman's version of this conversation is somewhat different. He testified at his own hearings that he offered Sidney "reassurance" about Libby but that he did not recall Sidney's asking him to come to the hospital. Wouldn't it have been in character for such "an aggressive, demanding individual" like Sidney to have asked him to come?, Terrence Sheehan asked. "Well," Dr. Sherman said, "I didn't think it was unusual at the time. ... I think I conveyed the impression that I was fully informed about what was going on. I certainly could have said 'I'll be there if there should be any problem.' "

The doctor who saw Libby after Maurice Leonard was a junior floor resident who had been at New York Hospital for nearly two years—Gregg Stone. On admission, Libby had been assigned to Luise Weinstein because she was the intern next in line to receive a new patient. Dr. Stone was the resident responsible for overseeing Weinstein's patients. Both he and Weinstein had come on duty Sunday at about nine A.M. and, in keeping with hospital practice, could have worked for thirty-two hours straight, unless the opportunity for a nap arose. Around 12:30 a.m.—it was now Monday, March 5, 1984—Stone came to the emergency room to see Libby. When Libby was taken upstairs, he followed, and completed his examination about two A.M. Libby denied all illicit-drug use, including marijuana, to Dr. Stone. He performed a more comprehensive examination than Dr. Leonard, whose diagnosis, on the chart, was simply "fever of unknown etiology." Stone noted the patient's "horrific thrashing about" and wrote that he suspected she had "just a viral syndrome with hysterical symptoms." Basically, Stone testified, he regarded Libby as a "medical" patient, to be treated as such. But he thought one aspect of her agitation—"large motor activities" such as "flailing her limbs, thrashing about in bed, moving her head side to side and, at times, fishtailing in bed"—was more consistent with "psychological origin because she was able to volitionally control these. . . . When we would ask her to stop them, she would stop them at will for a time," Stone said. "Then, when we would lose her attention, she would restart them." To break a second kind of movement, a "fine arrhythmic shaking" consistent with rigors, or chills, Stone suggested a twenty-fivemilligram intramuscular dose of Demerol, normally used as an analgesic, or pain reliever. The Demerol was not given until 3:37 A.M., after Stone had finished with Libby and left the floor. But that was a fateful moment—if not for the patient, certainly for her physicians at New York Hospital.

A mong Dr. Stone's other recommendations that night were Tylenol every three hours for a temperature exceeding 100.2 degrees, various blood and other cultures, and, in the morning, a special X-ray of the base of Libby's teeth and advice from a dentist. He testified later that he wanted to be sure "there wasn't a deep-seated abscess or an infection at the site of that tooth extraction since it seems that her illness dated back to that time. From a superficial examination there was no evidence of infection." Stone ordered antibiotics withheld on the grounds that no bacterial infection was apparent. And to make it easier to assess Libby's mental status, he discontinued her Nardil. At his hearing, Stone said he had been aware that Nardil interacted with stimulant drugs and with certain beers, wines, and cheeses that contain tyramine or aromatic amino acids. But he saw no high blood pressure or other signs of a Nardil reaction in Libby. The patient, he testified, had told him that she had not used the antidepressant in "at least several days," and a hypertensive reaction, he believed, would have occurred within minutes and dissipated within a day. Dr. Stone spoke to Dr. Sherman around two A.M. on March 5 for about twenty minutes. He reviewed his findings and tentative conclusions, focusing on a viral illness but including the possibility of inflammation of the brain, toxic shock syndrome, and an infection spreading into the bloodstream from an undetermined source. Like Dr. Leonard, he mentioned Libby's use of Nardil. Stone later said that he told Dr. Sherman he had ordered Demerol—something Sherman would say he did not hear. Stone did not ask Sherman to come to the hospital, because, again like Dr. Leonard, he did not think Libby's life was in danger. Sherman said he would see the patient in the morning.

Around three A.M., according to Sidney, Stone encouraged him and Elsa to leave. "At that point," Sidney recalled in his deposition, "I said 'What do you mean?' He said 'Well, you can't help her, and really it would be better, because she's so agitated, if you don't stay.' " Sidney responded by saying he wasn't going anywhere unless he talked to Dr. Sherman. But Stone said that he had just talked to Dr. Sherman and that the internist agreed. Again, Sidney was relieved. If Sherman wanted him to go home, and was not coming to the hospital, he thought, things must not be so bad. "So I went over to Libby and I said 'Baby, you know if there was anything wrong here Ray would be here, Dr. Sherman would be here.' She said, 'I know, Daddy.' Then I said, 'And they want us to go because you will rest easier, and things will be better for you, and we will pick you up in the morning.' And she said, 'Shloft gezunt,' and it means sleep well. She said that to me."

Whether Dr. Sherman, at home, was tired has not been made an issue in the Zion case, as it has with some of the house-staff doctors. Dr. Maurice Leonard, who faces no disciplinary charges, had been on duty only three hours when he examined Libby in the emergency room. But in January 1987 the grand jury—and, later, prosecutor Sheehan— strongly implied that Gregg Stone and Luise Weinstein were exhausted by the time they were treating her, roughly sixteen to nineteen hours after starting work. During the hearings, James Nolan, chairman of the department of medicine at the State University in Buffalo, testified that it was almost routine in a hospital to work at least nineteen hours straight, that there was a difference between being physically tired and mentally impaired, and that nineteen hours in a row, especially after a day off, should not normally "lead to excessive fatigue.'' There was no evidence, he said, to indicate that the judgment of Dr. Weinstein or Dr. Stone was impaired. Dr. Sherman, at his hearings, testified that Dr. Stone seemed "alert and very fully conscious and thorough" when he talked with him on the night Libby Zion died. Nothing, he said, suggested that Stone "was in any way impaired in his judgment because of physical or mental tiredness." Sometime after three A.M. Stone did go to his apartment, across the street from the hospital—presumably to rest. In accordance with hospital policy, he was reachable by beeper. The doctor who had taken charge of Libby by then was Luise Weinstein. There has been no evidence whatsoever that Dr. Weinstein's judgment was affected by lack of sleep. But she may well have been overworked.

Luise Weinstein came to New York Hospital as an intern in June 1983. After rotating through Memorial Sloan-Kettering, an affiliated institution that primarily treats cancer, she worked in various units and services of New York Hospital itself: intensive care; neurology; general medicine; renal, where she met Dr. Sherman. On the morning of Sunday, March 4, after a day off, she took up her duties on the third-floor ward of the hospital's Payson building, known as Payson 3. Because it was Sunday, Dr. Weinstein was covering during the daytime hours for two other interns; at night, as was routine even during the week, she would be the only intern in her area, responsible for about forty patients.

Carrying a list of patients' problems that had developed over Saturday night, Dr. Weinstein made rounds on Sunday morning with the resident and intern whose shifts were ending, and noted new admissions. As noon approached she drew blood samples and made certain that tests had been prepared for the laboratory. Afternoon rounds were conducted with Gregg Stone, ending about five P.M. Toward six she spent an hour or so examining a new admission, a man in his sixties with pulmonary-artery disease who had to undergo a cardiac catheterization. Another patient had collapsed. Others had AIDS, malignancies, fevers, respiratory and heart problems, disseminated herpes. Around 9:15 P.M. Dr. Weinstein had a pizza in a conference room on Payson 4. She then returned to her floor, conferred with a cardiology fellow about the patient who needed the catheterization, and went about evaluating patients' recent temperatures, restarting intravenouses, reviewing charts. By eleven P.M. she had discussed her patients' conditions with the chief resident on duty, Martin Carr.

Two hours later—around one A.M. on March 5—Dr. Weinstein was notified by Maurice Leonard in the emergency room that he was sending her a new patient, Libby Zion. Because all the beds on Payson 3 were filled, Libby would be "boarded" on Payson 5 next to the nurses' station, in a room with three other patients. At the hearings, Dr. Weinstein recalled Dr. Leonard saying that he had been unable to find the source of Libby's malaise and fever but that he suspected a viral infection. Weinstein went to the emergency room, passing Libby just as she was being put on an elevator. The patient, she testified, was moving about on a gurney "in a restless kind of random fashion." After talking to Dr. Leonard, who mentioned that Libby had been using Nardil, Weinstein followed her to Payson 5.

While Dr. Stone examined Libby in her room, Weinstein went through the chart from the emergency room. Taking the Physicians' Desk Reference (P.D.R.) from a shelf at the nurses' station, she looked up Nardil, a brand name she was unfamiliar with. She wondered whether Libby might have overdosed on the antidepressant, but it seemed doubtful. While she was reading, a nurse's aide told her that Libby had pulled out her intravenous tube. Weinstein went into the room and restarted it, something she would eventually have to do two or three times. It was around 2:30 A.M., while Dr. Stone was speaking on the phone to Dr. Sherman, that Weinstein began her formal evaluation of Libby, whose parents were just about to leave. The information she elicited from the patient—with some difficulty, she noted on the chart, because of Libby's "waxing and waning" agitation—did not vary significantly from what Stone had learned.

In her testimony, Weinstein said that Libby could not be specific about when she had last used Nardil, but placed it around the time her tooth was taken out and she began to feel sick. Weinstein understood that to mean four days earlier. Like Dr. Stone, she performed a complete neurological and physical examination, except for the pelvic area, which had been examined by Dr. Leonard. She drew blood for culturing for bacteria and prescribed the Demerol that Stone had recommended. Weinstein observed that Libby was able to pass urine at 3:30 A.M., indicating a correction of her dehydration.

The patient's vital signs—which had been taken six times between midnight and 2:45 a.m.—were stable. Her temperature was still 103; her blood pressure, 100/60 earlier, was now 110/70 lying and 96/60 standing; her pulse rate, down from 156 to 104 lying and 120 standing; her respirations, down from 32 to 24. At one point, Dr. Weinstein found Libby out of bed and walking around the room, her IV disconnected. She put Libby back to bed and, promising that she would not* say anything to the girl's parents, pressed her again about whether she had taken any drugs or medication before coming to the hospital. "She said no, she didn't take anything," Weinstein testified. "She turned her back to me." Under questioning by her attorney, Weinstein said that she had not ordered a drug screen immediately because the results would not have been available for days. She also testified that she did not notice any change in Libby's behavior or appearance after the Demerol was administered at 3:37 A.M.

Dr. Weinstein laid plans for the dental X-ray and consultation—and a psychiatric consultation, if needed—ordered a check of vital signs every four hours, obtained the latest lab data, and finished writing her three-page note at the nurses' station. She would see Libby with Dr. Sherman in the morning, between seven and eight A.M. Essentially, Weinstein's working diagnosis was no different from Dr. Stone's. Before returning downstairs to Payson 3 about four A.M., she considered giving the nurses discretion to administer a sedative to Libby. But she decided to see what would "happen with time."

She did not have to wait long. About Oten minutes after Dr. Weinstein had left the floor, a young nurse who had not been in Libby's room since two A.M. found the patient trying to climb over the side rails of her bed, her "entire body in movement." The nurse, Jerylyn Grismer, was joined by a more experienced nurse, Myra Balde, but when the two were unable to quiet Libby, Grismer picked up a house phone just outside the room and called Dr. Weinstein. It was now about 4:15 A.M. As she later testified, Grismer felt that Libby needed some form of restraint to avoid hurting herself. Dr. Weinstein said to use a Posey, or jacket, to tie Libby's chest to the bed. Although Weinstein was unaware of it, the nurses soon escalated the precaution to what is known as a "four-point" restraint, tying down the patient's ankles and wrists as well.

Within ten minutes Grismer called Dr. Weinstein a second time and, according to the note she wrote that morning, asked the intern to "come up and see patient, as patient needs some sort of sedation." Weinstein ordered one milligram of Haldol for Libby, which was given at 4:30 A.M. She did not come back to Payson 5 and, she testified, did not recall being asked to do so. Dr. Weinstein felt she was needed on Payson 3 after an absence of two to three hours, and Grismer, she said, had not described Libby in terms that were "dramatically different" from what she herself had just witnessed. While there were no emergencies on Payson 3 at that moment, it was Dr. Weinstein's last night on that service and, she testified, "there are many things you want to have ready for the new intern who doesn't know these patients."

Jerylyn Grismer, who had graduated from nursing school the previous May, looked in on Libby at about five A.M. The patient was sleeping comfortably, "her color was still pink, her respirations were unlabored and regular," Grismer testified. "Her skin was comfortable—had a comfortable temperature to the touch because I went over to the bed and touched her." At 5:30 A.M. Libby was seen by Myra Balde, who had worked as a nurse for sixteen years in her native Guyana before coming to New York Hospital in 1983. She testified that when she replaced Libby's intravenous fluids the young woman was still sleeping. Her color "didn't look anywhere suspicious," Balde said. "She didn't look pale, she didn't look blue, anything of this sort. She looked okay." At six A.M., when Balde returned to give Libby Tylenol, she found that someone—it has never been established who it was—had removed the patient's restraints. Otherwise, she said, Libby seemed unchanged. When Balde helped her to sit up and take the Tylenol, she opened her eyes but did not speak. Her skin was warm and flushed, the nurse recalled, but she "didn't feel burning up because I would have noted it."

A half-hour later, at 6:30 A.M., a nurse's aide arrived to take Libby's temperature. It was 108. In a panic, the aide ran to Balde, who rushed for cold compresses and sponges. Jerylyn Grismer called Dr. Weinstein, who ordered a plastic cooling blanket and, according to her testimony, was reaching for examining instruments to take upstairs when, at 6:40 A.M., Grismer sounded the code for an emergency cardiac-resuscitation team. The team, led by Martin Carr and aided by Luise Weinstein and a resident at the electrocardiogram machine, worked for fifty minutes, to no avail. Jerylyn Grismer and Myra Balde were in tears. At 7:30 A.M. Libby Zion was pronounced dead.

Sidney and Elsa were asleep when the phone rang at 7:45. Dr. Sherman, who had rushed to the hospital after a call from Dr. Weinstein saying that Libby had "gone flat line," told Sidney to get there immediately—"it's real bad." As Sidney hung up and turned to his wife, the phone rang again and Elsa picked it up. It was Luise Weinstein. "I want to tell you that we did everything we could for Libby." Elsa realized the doctor was speaking in the past tense.

An autopsy was performed on Libby Zion the day after she died. Dr. Jon Pearl, a deputy chief medical examiner for the city, initially attributed her death to "bilateral bronchopneumonia, pending further study." But, in May 1984, after reviewing Libby's hospital chart and microscopic studies of her lung tissue, he signed the case off as "acute pneumonitis"—a generalized finding that is more descriptive than conclusive. When he appeared before the grand jury in 1986, Pearl said it was highly unlikely that the pneumonia alone was extensive enough to have killed Libby. One of Dr. Pearl's theories—although it was not based on any data from the autopsy—was that Libby had been adversely affected by the twenty-five-milligram dose of Demerol at 3:37 A.M. on March 5. That hypothesis hardened into Sidney Zion's accusation that his daughter died because of "the needle." And the state of New York, through Terrence Sheehan, has taken that position. In his opening statement at the hearings, Sheehan said that Weinstein's and Stone's "wholesale failure to follow elementary principles of diagnosis and therapy contributed to [Libby's] unnecessary death." He went on to say that it was the Demerol, in conjunction with the Nardil Libby was taking, that "created fatal complications."

Demerol is contraindicated with Nardil. The 1983 P.D.R. entry on Nardil—which Dr. Weinstein read before examining Libby and before carrying out Dr. Stone's recommendation to give Demerol for her chills and shaking—warns that "death has been reported in patients who received meperidine [Demerol] concomitantly." The entry on Demerol, which Dr. Weinstein did not read on March 5, says that "therapeutic doses of meperidine have occasionally precipitated unpredictable, severe and occasionally fatal reactions" in patients who have received drugs such as Nardil "within 14 days." At her hearing, Weinstein testified that, when she "read through" the P.D.R. entry on Nardil, including its passage on contraindications, she did not see the sentence warning against the use of Demerol. Her review of the P.D.R., she said, was motivated by her concern that Libby might have had an overdose of Nardil. When the Demerol was given an hour or so later, she did not look up that drug in the P.D.R., because she felt she was familiar with it. "I didn't realize that there was a contraindication," she testified, "and I felt comfortable with my knowledge of Demerol and with what I had learned about MAO inhibitors [such as Nardil]."

Sheehan's position is that Weinstein and Stone—the latter did not consult the P.D.R. that morning regarding either drug—should have known about the contraindication. And this issue—what Sheehan once called "the whole case"—has spawned thousands of words at the Weinstein-Stone hearings. Paul Rooney, Dr. Weinstein's lawyer, and Maurice McDermott, the lawyer for Dr. Stone, called one expert after another who said they themselves were unaware in 1984 of the then relatively obscure contraindication between Nardil and Demerol. Moreover, the experts said that unless a doctor suspected he was weak in his knowledge of a particular drug, he could not be faulted for failing to consult the P.D.R. "You have to know that you don't know something to use the P.D.R.," said Richard Gorlin, chief of medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. George Simpson, director of clinical psychopharmacology at the Medical College of Pennsylvania, said that he hated to "knock" the P.D.R.—"It is the best we have, it is very good. But it is not—it was never brought down from the mountains." Paul Rooney, confronting the drug-interaction issue, made much of the fact that no one knows exactly when Libby last took Nardil—something for which the house staff is faulted by Sheehan.

Virtually all of the defense experts testified that, in the aftermath of the Zion case, they would not now give Demerol to a patient who was taking Nardil. Some said they might not even have done so in 1984. But all who were asked said that they did not believe Demerol had killed Libby Zion. Harold Fallon, chairman of the department of internal medicine at the Medical College of Virginia and former chairman of the American Board of Internal Medicine, the certifying board, said that twenty-five milligrams of Demerol would have been no more than half the "therapeutic" dose referred to in the P.D.R. entry on that drug. Ferid Murad, former acting chairman of medicine at Stanford University Medical Center and an editor of Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, a standard text, said he did not know of any medical reports of a Demerol reaction to Nardil in which the Demerol was less than seventy-five to one hundred milligrams. And any reaction, he said, would come within minutes, not hours.

Dr. Murad, who said he was probably one of the few physicians in the country who had not known about the Zion case, observed that the combination of medications Libby had taken in the months preceding her death were "rather remarkable." Some of them, too, he noted, were also contraindicated with Nardil. Like most of the other experts, Dr. Murad said the care provided Libby at New York Hospital was "really very good. It was excellent and I don't think anything done any differently would have probably altered the course." William McCormack, director of the infectious-diseases department at SUNY Health Science Center at Brooklyn, reflected the view of the other defense experts when he said that Dr. Weinstein was not required by accepted standards of medical practice to revisit Libby when the nurse called between 4 and 4:30 A.M. "All of us in the practice of medicine," he said, "have to deal with more than one patient at once. . . . We all have to make judgments as to what is the best utilization of our professional time and skill at any particular moment." Stone and Weinstein, Dr. McCormack said, had rendered "the finest of care, exemplary." Even the records they kept were "magnificent," he said. "I wish I could use them as teaching tools."

Terrence Sheehan tried to show that, whatever killed Libby Zion, the house staff were "in over their heads"; that, apart from fluids and Tylenol, Dr. Weinstein and Dr. Stone provided little, if any, "medical treatment" to Libby; that the patient's condition deteriorated right in front of the resident and intern and that her level of agitation increased between 3:37, when she received the Demerol, and 4:30, when she was given the Haldol; that a rise in her fever was predictable and that even Dr. Stone's order at 2 A.M. for cold soaks had been ignored until Libby went into cardiac arrest. But he generally got nowhere with the experts for the defense, and his frustration spilled out. When one of the defense witnesses insisted that Dr. Weinstein's failure to turn back to the P.D.R. might not constitute negligence, Sheehan accused him of having an "incredibly relativistic standard." If "someone believes they are familiar [with a drug] but they make a mistake, there's nothing wrong with that because what they did they felt was okay," Sheehan complained. "That's diametrically opposed to the legal system in this country and in the Western Hemisphere."

Paul Rooney fared better than Sheehan with the experts. In 1986 Dr. Ira Hoffman, the associate director of medicine at Lenox Hill Hospital, had been asked to review Libby's chart by a former Lenox Hill colleague, James Donaldson, who had become medical coordinator for the Health Department's professional-misconduct unit. On August 4, 1986, Hoffman wrote Donaldson to say that he found it "impossible to assess whether the death was preventable. In spite of the possibility of drug interaction and sepsis, it is impossible to say on my part whether the clinical patterns which appeared to accelerate adversely during the evening, night of March 4 and ended in the demise of the patient on the morning of March 5 could have been prevented."

In 1987, however, Hoffman became the state's main witness against Weinstein and Stone and, eventually, against Dr. Sherman as well. Under questioning by Sheehan, Hoffman said the house-staff care of Libby was "very inadequate," negligent. There were many things wrong: insufficient workup and diagnostic procedures; failure to obtain consultations, even in the middle of the night; misplaced emphasis on a "psychiatric component" to Libby's behavior that discouraged "medical" intervention; the administration of Demerol; Dr. Weinstein's decision not to return to the patient around 4:15 A.M.—"not professionally understandable to me"—and Dr. Stone's failure to revisit at all.

But under Rooney's cross-examination, Hoffman softened his criticism of Weinstein and Stone and blasted Dr. Sherman, against whom a state panel, in 1986, had declined to vote misconduct charges. By "running this case from his bed," Hoffman testified, Sherman "blew it as a practicing physician." It was Sherman, the attending physician, who had "the ultimate responsibility" for Libby. "Somebody should have said to him, get your ass in here, doctor, this patient is in a lot of trouble. But I guess one doesn't do that in certain institutions."

In August 1987, a week after Hoffman gave this testimony, the state decided to file charges against Dr. Sherman after all. At the subsequent hearings, Sherman told Sheehan that it was "absurd" to think that at a teaching hospital "every single patient in every kind of circumstance has to be seen" by an attending physician to decide whether or not a case is serious. "Clearly, we don't operate our hospitals that way." Dr. Sherman testified that he did not think Libby's condition was "severe," from what he was told by Stone and Leonard that night, and it did not appear to him that "I would accomplish anything more by being" at the hospital before eight A.M. Curiously, a year after his testimony in the Weinstein-Stone hearings, even Dr. Hoffman seemed to agree that it was reasonable for Dr. Sherman to "put the phone down and assume that four or five hours is not going to make a difference."

Like Dr. Hoffman, Sherman said he did not know why Libby died. Nor did Dr. Lewis Goldfrank, another expert witness called on rebuttal by the prosecution to shore up what appeared to be a faltering case. Dr. Goldfrank, director of emergency medicine at Bellevue Hospital and the New York University Medical Center, testified that while there was no supporting evidence other than Libby's symptoms, "it would not surprise me" if she had taken an illicit drug like angel dust. He conceded that doctors at New York Hospital had considered the drug "issues"—in fact, he said, Dr. Leonard had done a "careful assessment" of Libby in the emergency room, Dr. Stone and Dr. Weinstein had conducted "thorough" examinations of Libby upstairs and written "meticulous" notes, Dr. Stone had made a "particularly thoughtful analysis of the potential problems," and Dr. Weinstein had "planned to the best of her ability." But the house staff, he said, had not undertaken what Sheehan called "aggressive treatment."

Even though the resident and intern were in accord with Dr. Sherman's ideas for treating Libby, and had no evidence that he did not appreciate the "seriousness" of the situation, Dr. Goldfrank said, they "should have been" dissatisfied and should have gone to other senior physicians. ' 'They are entitled to have supervision at all times when they must manage patients as seriously ill as this woman."

The prospect of the house staff going over Dr. Sherman's head—unless they thought he was a "fool"—seemed a little too much for the members of the hearing panel, whose chairman had already chastised Dr. Goldfrank for "extensive editorializing." "All I want to know," one of the doctors on the panel asked, "is if, in their wisdom or lack of wisdom, they assumed Dr. Sherman, who was their superior, gave them adequate advice, adequate teaching on the telephone that night with regard to the patient, in the middle of the night, with what facilities they had available, was their action or lack of action in looking after the patient less than adequate care? That's the bottom line that I'd like you to answer a yes or a no."

Yes, Dr. Goldfrank allowed, that would be acceptable care.

But Luise Weinstein sits in that little hearing room, sits there, it seems to Sheehan, like a nun. Later this month, perhaps next month, the panel will tell David Axelrod, the state health commissioner, whether it thinks she and Dr. Stone acted reasonably and prudently. In all likelihood, Sidney Zion will not be satisfied. But, whatever happens to the doctors, he has succeeded in changing the way medicine is practiced, at least in New York. Beyond the new rules limiting the hours house-staff members can work in a row are reforms that mandate their closer supervision and that tighten the conditions under which physical restraints can be used. "Sidney has won already; he's the real victor," said a senior physician at New York Hospital. "He's changed the way we do business."

Sidney Zion is persuaded that the cause of his daughter's death is, as he said in a deposition for his civil suit, "the doctors." Zion acknowledges that during the entire time he was at the hospital, from approximately midnight until 2:45 A.M., "it seemed like [Libby] was in good hands." Luise Weinstein struck him then as "kind of a sweet-looking person in a way." But he now believes that "a great conspiracy" was perpetrated "to get rid of us, throw us out of that hospital so they

could get rid of Libby and pay no more attention to her. . . . They decided that she was a hysteric, a crazy kid, and they didn't give a goddam whether she died." It was, he said, "an utter and absolute abandonment of a patient by the staff of New York Hospital." But his suit, if it goes forward, is no more apt to resolve why Libby died than the hearings have, and it is likely to be an even more hotly fought and messy contest in an even more public arena.

New York Hospital, which is not a direct party to the Weinstein-Stone or Sherman hearings, is expected to defend itself in court by showing, in part, that Libby or her parents withheld information from its doctors about her drug use and medical history, including two operative procedures about which Sidney and Elsa say they knew nothing. The extent of distrust between the hospital and the Zions, or their respective lawyers, was illustrated in 1985 when the hospital, in an attempt to ascertain whether Libby had had viral influenza, asked the medical examiner's office for a small piece of lung tissue from the autopsy. The hospital promised to report back its test result. The medical examiner's office supported the hospital's request, saying "the proposed study could be of value." But lawyers for the Zion family vetoed the test.

The hostility was compounded in early 1987 when, under pressure following criticism from the grand jury, New York Hospital issued a news release likening Libby's death to the clearly cocainerelated deaths of athletes Len Bias and Don Rogers. "Certainly," the release said, "the recent death of two prominent athletes demonstrates the unpredictable effects of cocaine ingestion and points to cocaine, found on autopsy, as the cause in whole or in part of the sudden cardiac collapse of this patient." Sidney Zion was furious, because the evidence that cocaine played a role in Libby's death was never more than presumptive. Postmortem analyses by the medical examiner's office in May 1984 suggested a "trace" of cocaine on a cotton swab of Libby's nose and a "considerably stronger" reading on an impure blood-culture sample of hers provided by the hospital. But there was no confirmation of cocaine in her body—including her blood, bile, and urine. The quality of the original tests has been questioned by both those who suspect cocaine was present and those who don't.

At the Weinstein-Stone hearings, doctor after doctor has admitted to being stumped as to the cause of Libby Zion's death. Some speculated that the death was due to a viral problem, although the autopsy provided little, if any, basis for this. Others said the death might have stemmed from a drug interaction unrelated to Demerol or cocaine. One medical witness reflected the views of other experts when he said he could not think of more that could have been done to save Libby, "because I don't know why she died." Libby, he summed up grimly, came into the hospital with the illness that took her life, an illness that, having eluded her doctors, "continued inexorably on toward the final result."

An intriguing possibility, but one hardly mentioned by the experts, is whether Libby's death was somehow connected to the infected, badly broken-down tooth that was extracted just before she became ill. It seems unlikely, because there was no significant swelling in that area of her mouth and the inflammation under the tooth appears to have been a long-term rather than an acute condition that could have seeded her body with bacteria. Still, the opportunity to lay this theory to rest has been lost. Only one blood culture was examined by the hospital for bacteria after her death; none was tested for this purpose by the medical examiner's office. No bacteria were found in the hospital sample, according to a report on March 14, 1984, but one culture is often an insufficient guide. Libby's white-cell count showed a marked "shift to the left," usually associated with a bacterial, not a viral, infection. At the autopsy, Dr. Pearl cut into the gum but saw no reason to go further and dissect the jaw, where an abscess might have developed.

But if the rotting tooth did not precipitate an illness that thrived unchecked, there may have been another cause, this one almost entirely overlooked. At the autopsy, the medical examiner's office found a high level of salicylate, or aspirin, in Libby's blood, both in the culture from the hospital and in the postmortem blood. The salicylate level was "consistent with" an unusual amount of aspirin that could have been taken over the days preceding her death or with more than a dozen aspirin, or Percodan, tablets taken hours before she entered New York Hospital. But, as far as the record shows, Libby took Tylenol and not aspirin. She supposedly took only one Percodan from a twenty-tablet bottle, although all but five tablets were gone from the bottle when it was turned over to the grand jury in late 1985. So how Libby came to have this level of salicylate—which, at home as well as at the hospital, could have caused agitation but camouflaged a much worse fever than the thermometer registered, a fever that, whatever its source, might all along have been signaling tragedy—remains unexplained.

Could Libby have been so accustomed to the casual consumption of drugs, licit or illicit, that she inadvertently contributed to her own death? It is hardly certain that if Libby had been more forthcoming about her use of drugs to the doctors at New York Hospital her treatment, or the outcome of her illness, would have been any different. But it is possible that she had so masked a raging fever with aspirin or Percodan that the doctors did not appreciate her real condition. Arterial-bloodgas tests that might have suggested the presence of salicylate when she arrived at the hospital were not done until Libby was near death.

Whether earlier tests would have helped is just one question in a case full of "what ifs." What if Dr. Sherman had come to the hospital? What if Libby had not been "boarded" on a floor two stairwells away from where Luise Weinstein had her other patients that night? What if an intern who was stationed on Libby's floor, and who counseled nurse Grismer at about 4:30 A.M. to call Dr. Weinstein, had himself intervened in the case? What if Weinstein had come back when first called by Grismer? The young nurse testified that she was increasingly concerned about Libby and felt that "something odd was occurring." "But because of your lack of experience you didn't really know the severity of it, is that right?," Terrence Sheehan asked. "Yes," said Grismer. "I think that's fair to say." What if, long before Libby Zion ended up in New York Hospital, there had been better coordination among her regular doctors? There are no definitive answers to these and other questions. In the sense that the real answers are buried with her and are not going to be disinterred for the comfort or enlightenment of either father or doctors, they are like much else in the clouded case of Libby Zion, the girl who wanted to be famous.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now