Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

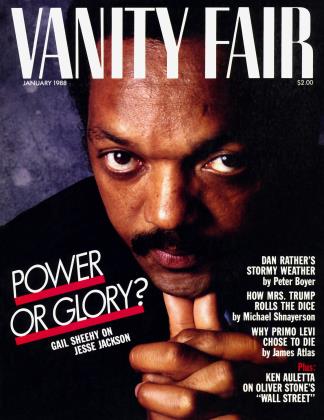

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWhat does he want? Even as Democratic candidate Jesse Jackson wins hearts and minds in the Midwest, very little is known about the man behind the message. GAIL SHEEHY discovers that a sense of shame, a family rivalry, and an insatiable need for legitimacy have forged his character and drive. But does he really want the White House?

January 1988 Gail SheehyWhat does he want? Even as Democratic candidate Jesse Jackson wins hearts and minds in the Midwest, very little is known about the man behind the message. GAIL SHEEHY discovers that a sense of shame, a family rivalry, and an insatiable need for legitimacy have forged his character and drive. But does he really want the White House?

January 1988 Gail Sheehy View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now