Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

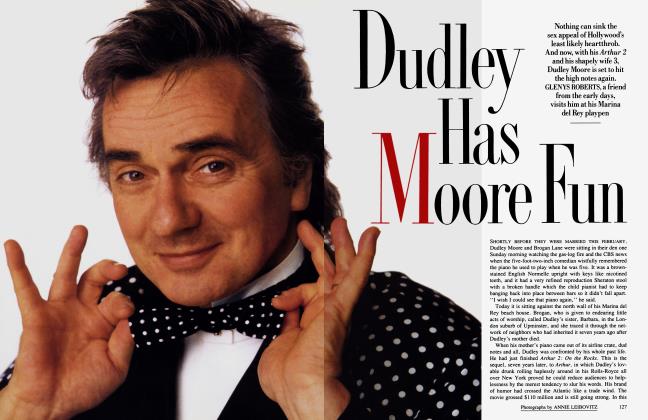

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA budding writer and a blonde divorcée, doomed love and willful self-deception. PHILIP ROTH recalls meeting his real-life nemesis

August 1988 Philip RothA budding writer and a blonde divorcée, doomed love and willful self-deception. PHILIP ROTH recalls meeting his real-life nemesis

August 1988 Philip RothI'd already noticed her long before that evening in Chicago when I introduced myself out on the street and persuaded her to have a cup of coffee with me in Steinway's drugstore, a university hangout only a few blocks from where she lived. Out of either shyness or savoir faire, I'd never in my life tried as blatantly to pick anybody up, which indicates not so much that fate had a hand in my trying now, but that I was determined—as culturally inclined as I was psychologically resolved—to have my adventure with this woman who appeared to be the incarnation of a prototype.

In October 1956, I was not yet twenty-four, the army was behind me, and my second published short story had been plucked from a tiny literary magazine and selected for Martha Foley's Best American Short Stories 1956. I was an instructor (as well as a Ph.D. candidate) at the University of Chicago, I was sporting a tan glen-plaid Brooks Brothers University Shop suit that I'd bought with army separation pay in order to meet my college composition classes, and, having just come from a cocktail party at the Quadrangle Club for new faculty members, I had some four or five ounces of bourbon enkindling my flame. Roaring with confidence, then, and, feeling absolutely free ("...they were drunken, young, and twenty .. .and they knew that they could never die.'' T. Wolfe), I corralled her in the doorway of Woodworth's bookstore and said something like "But you must have a cup of coffee with me—I know all about you.'' "Do you? What's there to know?" "You used to be a waitress in Gordon's." Gordon's was another university hangout, a restaurant just next door to Woodworth's. "Was I?" she replied. "You have two small children." "Do I?" "You come from Michigan." "And how do you know that?" she asked. "One day at Gordon's I saw your children with you. A little boy and a girl. About eight and six." "And just why have you bothered to remember all this?" "You seemed young to have those kids. I asked somebody and they told me you were divorced. They told me you were once an undergraduate here." "Not long enough for it to matter." "They told me your name. Josie.* I came here as a graduate student in '54," I told her. "I used to have lunch at Gordon's. You waited on me and my friends."

I cast myself as the parfit Jewish knight dispatched to save one of their own from the worst of the Gentile dragons.

"I'm afraid I don't have that good a memory," she said. "I do," I replied, and doggedly witty, doggedly clever, doggedly believing myself utterly impregnable, I got her finally to accede—I would rarely get her to do that again—and to walk down the block and sit with me in a booth in the window of Steinway's. There the published young instructor presented his plumage in full, while Josie, quizzical and amused and flattered, said—in an ironic allusion to her powers to inflame—that she couldn't figure out what I was so fervent about.

But I was fervent then about almost everything, and that evening fervent in the extreme because of those straight bourbons that I'd been drinking at the faculty-club party, where I was the university's youngest new faculty member and arguably its happiest. If she couldn't understand why the fervor had fastened on her it was because what I experienced at twenty-three as the power of a fascinating prototype felt to her at twenty-seven like the sum of all her impediments. The exoticism wasn't solely in her prototypical blue-eyed blondeness, though she was blue-eyed and very blonde, a woman whose squarish, symmetrical face, no matter how worn down by furious combat, could still manage to look childlike and tomboyish in a woolen ski hat; it wasn't in her prototypical Gentile appearance, though she was Gentile-looking in a classically volkisch way; it wasn't in her Americanness, either, though her speech and dress and manner made her a virtual ringer for the solid, energetic girl in the cheery movies about America's heartland, a friend of Andy Hardy's, a classmate of June Allyson's, off to the prom in his jalopy with Carleton Carpenter. Though this hardly made her any less American, she was actually a small-town drunkard's angry daughter, a young woman already haunted by grim sexual memories and oppressed by an inextinguishable resentment over the injustice of her origins; hampered at every turn by her earliest mistakes and driven by fearsome need to bouts of desperate deviousness, she was a more likely fair-haired heroine for the scrutiny of Ingmar Bergman than for the sunny fantasies of MGM.

What was exotic, then, wasn't the prototypical embodiment of the Aryan Gentile American woman—hundreds of young women no less prototypical had failed to excite my interest much at college—but, as I'd already sensed in Gordon's restaurant back when she was still a newly divorced waitress with two small kids and I was a U of C graduate student, that she was that world's victim, a dispossessed refugee from a sociobiological background to which my own was deemed, by both Old and New World racial mythology, to be subservient, if not inferior.

If our contrasting family endowments didn't accord, in fact, with ancient racial mythology, they did conform to the simplifications about the inner resources of the Jews and the corrupting vices of the goyim that had sifted into my own sense of human subdivision from the beliefs of my Yiddish-speaking grandparents. Educated on their ancestors' and their own experience of violence, drunkenness, and moral barbarism among the Russian and Polish peasantry, these unworldly immigrants would not have imagined it to be quite as culturally illuminating as did their highly educated American grandson that a solid female specimen of earthy Gentile stock could be blighted at the core by irresponsible parenting, involving not merely alcoholism and petty criminality but, as she would eventually allege, a half-realized attempt at childhood seduction. That her father had never been able to hold down a job successfully or give up the bottle and wound up serving time for theft in a Florida jail would have seemed to my grandparents par for the course. Nor would they have found themselves anthropologically beguiled to learn that the divorced woman's own little boy and girl happened already to be enduring a childhood fate no less harsh than her own. It would simply have substantiated their belief in Gentile family savagery to hear how her Gentile husband (who, according to Josie's very dubious testimony, had "browbeaten" her into conceiving the second child, just as he had "irresponsibly" knocked her up, a single girl starting college, to conceive the first) had "stolen" the two Gentile children from their Gentile mother and shipped them to be raised by others, more than a thousand miles from her arms, in Phoenix, Arizona. Despite her avowal of gruesome victimization at the hands of yet another merciless shavgitz, my grandparents might even have surmised that the woman, having discovered that she was emotionally incapable of mothering anyone, had herself effectively let the two children go. She would have seemed to them nothing more or less than the legendary Old Country shiksa-witch, whose bestial inheritance had doomed her to become a destroyer of every gentle human virtue esteemed by the defenseless Jew.

Though no one mentioned here is a fictitious character, a few names, as well as some identifying details, have been changed where I thought it advisable. —P.R.

Raving within and stolidly blonde without—Josie would have seemed to my grandparents the incarnation not of an American prototype but of their worst dream. And just because of that their American grandson refused to be intimidated and, like a greenhorn haunted by the terrors of a vanished world, to react reflexively and run for his life. I was, to the contrary, exhilarated by this opportunity to distinguish at first hand between American realities and shtetl legend, to surmount the instinctive repugnance of my clan and prove myself superior to folk superstitions that enlightened, democratic spirits like me no longer had dignified need of in the heterogeneous U.S.A. And to prove myself superior as well to Jewish trepidation by dint of taming the most fearsome female that a boy of my background might be unfortunate enough to meet on the erotic battlefield. What might signify a dangerous menace to the ghetto mentality, to me— with my M.A. in English and my new three-piece suit— looked as though it had the makings of a bracingly American amorous adventure. After all, the intellectually experimental, securely academic environs of Chicago's Hyde Park were as far as you could hope to get from the fears of Jewish Galicia.

During the day Josie worked as a secretary in the Division of Social Sciences, a job that she liked and that brought her into contact with distinguished visitors like Max Horkheimer, the Frankfurt sociologist, who enjoyed her company and sometimes took her to lunch or to the faculty club for a drink. The job had helped enormously to get her adjusted to her new life after the frantic period of near breakdown following the loss of her children. We met and became lovers just as she had begun to enter the most hopeful period of her life since the aborted undergraduate year at the University of Chicago a decade earlier, when she believed she had escaped Port Safehold, Michigan, and everything there that threatened to destroy her.

Upon my return to Chicago, I'd lived first in a divinity-school residence hall and then in a small apartment—one room with a kitchen—a few blocks from the university. I went off from there every weekday from 8:30 to 11:30 A.M. to teach composition and, a couple of afternoons a week, to take courses toward a Ph.D. in the graduate English department. The other afternoons I sat squeezed in at my kitchen table, where the daylight was stronger than it was anywhere else in the minute flat, and wrote short stories on my portable Olivetti. In the evenings I walked over to Josie's sizable railroad flat carrying with me a wad of freshman essays that I'd correct and grade in her living room after we'd had dinner together and while she got on with chipping away the layered paint to reach the bare pine mantel of the fireplace. I thought it was game of her, after her day at the office, to be laying new linoleum in the kitchen and stripping the paper off the bathroom walls, and I admired the enterprising way in which she partially met the costs of the apartment—which had to be large, she said, so the children could visit during their Arizona school vacations—by renting a back room to a happy-go-lucky premature hippie, a U of C dropout who unfortunately didn't always have money for the rent.

Our evenings in Josie's apartment signaled to me that the aspiration that had carried me away from Newark and off to Bucknell University at eighteen had been triumphantly realized. I was at last a man. At twenty-three I was independent of my family, though I still phoned them a couple of times a month, wrote occasional letters, and made the trek east at Christmastime to see them; I was settled into a desirable if tedious teaching position at a prestigious university in a city neighborhood where there were lots of secondhand bookstores and plenty of original intellectual types; and above all, I was conducting my first semi-domesticated love affair where—even though their spectral presence was gigantic— nobody's parents were actually nearby, a love affair with a woman even more profoundly on her own than I was. That she was four years older than I seemed only further evidence of my maturity: our seemingly incompatible backgrounds attested to my freedom from the pressure of convention and my complete emancipation from the constraining boundaries protecting my pre-adult life. I was not only a man, I was a free man.

Since the summer of my Bucknell graduation I'd been carrying in my wallet the photograph of a college student from suburban north Jersey, Gayle Milman, a Jewish girl whose family history and personal prospects couldn't have been less like Josie's; she was quick-witted, intelligent, and vivacious, quite pretty, and possessed of the confidence that's often the patrimony of a young woman adored since birth by a virile, trustworthy, successful father. The hallmarks of the Milman family were solidarity and confidence. Could Josie have been disarmed of her resentful defiance and permitted to press her nose up against the glass of the picture window of the Milmans' large suburban house, she might well have stood there weeping with envy and wishing with all her heart to have been transformed into Gayle. She magically sought something approximating that implausible metamorphosis by deciding to marry me against all reasonable resistance and, on top of that, to become a Jew.

"Oh," cries Peter Tamopol in My Life as a Man, pining for the Sarah Lawrence senior whom he'd cast off in favor of his angry nemesis, "why did I forsake Dina Dombusch—for Maureen!" Why did I forsake Gayle for Josephine Jensen? Over a period of some two years, while I was in graduate school and in the army, Gayle and I were equally caught up in an obsessional passion whose intensity was undiminished despite the passage of time; yet, returning to Chicago in September 1956, I thought my voyage into manhood, wherever it might be taking me, could no longer be impeded by this affair which, as I saw it, had inevitably to resolve into a marriage linking me with the safe enclosure of Jewish New Jersey. I wanted a harder test, to work at life under more difficult conditions.

Two years later she turned up pregnant again. By then we no longer had anything resembling a love affair, only a running feud focused on my character flaws.

The joke on me was that Gayle had an enigmatic adventure of her own to undertake and, after graduating from college, propelled by the very gusto and self-assurance that had germinated in the haven of her father's hothouse, for over a decade led a single life in Europe whose delights had little in common with the pleasures of her conventional upbringing. From the stories that reached me through mutual friends, it sounded as though Gayle Milman had become the most desirable woman of any nationality between the Berlin Wall and the English Channel; meanwhile, the outward-bound voyager who refused to curb his precious independence by even the shadow of a connection with the provincial world he'd outgrown had sealed himself into a joyless existence, rife with the most preposterous, humanly meaningless responsibilities.

I had got everything backward. Josie, with her chaotic history, seemed to me a woman of courage and strength for having survived that awful background. Gayle, on the other hand, because of all the family security and all the father love, seemed to me a girl whose comfortable upbringing would keep her a girl forever. Gayle would be dependent because of her nurturing background and Josie would be independent because of her broken background! Could I have been any more naive? Not neurotic, naive, because that's true about us too: very naive, even the brightest, and not just as youngsters either.

The first months Josie and I were together I talked much of the time about writing, bought her my favorite paperbacks, lent her heavily underlined Modern Library copies of the classics, read aloud pages from the novelists I admired, and began after a while to show her the manuscripts of the stories I was working on. When I was asked to contribute movie reviews to The New Republic at twenty-five dollars a shot (a job offered to me as a result of a little satire about Eisenhower's evening prayer that The New Republic had reprinted from the Chicago Review), we went to the films together and talked about them on the way home. Over dinner we educated each other about those dissimilar American places from which we'd emerged, she badly impeded and vulnerable—and only now sufficiently free to try valiantly to recover her equilibrium and make a new life as an independent woman—and I, from the look of it, fortified, intact, and hungry for literary distinction. The stories I told of my protected childhood might have been Othello's tales about the men with heads beneath their shoulders, so tantalized was she by the atmosphere of secure, dependable comfort that I ascribed to my mother's genius for managing our household affairs and to the dutiful perseverance of both my parents even in their years of financial strain. I spoke of the artistry practiced within my mother's aromatic kitchen with no less enthusiasm than when I enlightened her about the sensuous accuracy of Madame Bovary. Because the grade and high schools I attended had been virtually down the street from our house, I had as a boy gone home for lunch every day—the result, I told her, was that after I'd returned from teaching my morning classes and changed from my new suit into my old writing clothes the first whiff of Campbell's tomato soup heating up in the kitchen of my little Chicago flat could still arouse the coziest sense of anticipation and imminent, satisfying consummation, yielding what I had only recently learned to recognize as a "Proustian" thrill (despite my inability during consecutive summers to get beyond page 60 of Swann's Way).

Was I exaggerating? Did I idealize? I don't know—did Othello? Winning a new woman with one's narratives, one tends not to worry about what I once heard an Englishman describe as "overegging the custard." I think now that what encouraged me to disclose to Josie, in such loving detail, memories that would have been entirely beside the point with Gayle Milman—the daughter of a Jewish household far more of a lotusland to its offspring than my own— was an innate taste for dramatic juxtaposition, an infatuation with the coupling of seemingly alien perspectives. My history as the gorged beneficiary of overdevotion, overprotection, and oversurveillance within an irreproachably respectable Jewish household was recounted in alternating sequence with her own life stories and formulated, I think, as a moral antidote to flush from her system the poisonous residue still tainting her belief in the possibilities for fulfillment. I was wooing her, I was wowing her, I was spiritedly charming her—motivated by an egoistic young lover's predilection for intimacy and sincerity, I was telling her who I thought I was and what I believed had formed me, but I was also engaged by a compelling form of narrative responsory. I was a countervoice, an anti-theme, providing a naive challenge to the lurid view of human nature that emerged from her tales of victimized innocence, first as an only child raised from her earliest years as the not entirely welcome guest—along with her long-suffering mother and semi-employable father—in the house of her Grandfather and Step-grandmother Hebert and then at the hands of the high-school sweetheart whom she'd married and whom she had reason, she told me, to despise forever.

She would despise him forever. I was as hypnotized—and as flooded with chivalric fantasies of manly heroism—by her unforgiving hatred of all the radically imperfect Gentile men who she claimed had abused her and had come close to ruining her as she was enchanted—and filled with fantasy— by my Jewish idyll of neatly ironed pajamas and hot tomato soup and what that promised about the domestication, if not the sheer feminizing, of unmuzzled maleness. The more examples she offered of their irresponsible, unprincipled conduct, the more I pitied her the injustices she had had to endure and admired the courage it had taken to survive. When she reviled them with that peculiarly potent adjective of hers, "wicked"—which I till then had associated primarily with people like the defendants at Nuremberg—the nearer I felt drawn to a world from which I no longer wished to be sheltered and about which a man in my intended line of work ought really to know something: the menacing realms of benighted American life that so far I had only read of in the novels of Sherwood Anderson and Theodore Dreiser. The more graphically she illustrated their callow destructiveness of every value that my own family held dear, the more contempt I had for them and the more touching examples I provided of our exemplary history of harmlessness. I could as well have been working for the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith—only instead of defending my minority from anti-Semitic assaults on their good name and their democratic rights, I cast myself as the parfit Jewish knight dispatched to save one of their own from the worst of the Gentile dragons.

Four months after we'd met, Josie discovered she was pregnant. I couldn't understand how it had happened, since even when she claimed it was a safe time of the month and saw no need for contraception, I insisted on her using a diaphragm. We were both stunned, but the doctor, an idealistic young neighborhood G.P. who had been treating Josie at very modest rates, came around to her apartment to confirm it. Sitting gloomily over coffee with him in the kitchen, I asked if there was any way to abort the pregnancy. He said that all he could do was try a drug that at this stage sometimes induced heavy bleeding that then required hospitalization for a D&C. The chances were slim that it would work—but astoundingly it did; in a matter of days Josie began to hemorrhage, and I took her to the hospital for the scraping. When she was back in her room later in the day l returned to visit, bearing a bunch of flowers and a bottle of domestic champagne. I found her in bed, as contented-looking as a woman who had given birth to a perfect child and talking brightly to a middle-aged man who turned out to be not a member of the medical staff but a rabbi who served as one of the hospital chaplains. After he and I exchanged pleasantries, the rabbi left her bedside so that Josie and I could be alone. I said to her suspiciously, "What was he doing here?" Perfectly innocently she replied, "He came to see me." "Why you?" "On the admissions form," she said, "under religion, I wrote 'Jewish.' " "But you're not Jewish." She shrugged, and under the circumstances I didn't know what more to say. I was perplexed by what seemed to me her screwy mix of dreaminess and calculation, yet still so relieved that we were out of trouble that I dropped the interrogation, got some glasses, and we drank to our great good luck.

Two years later she turned up pregnant again. By then we no longer had anything resembling a love affair, only a running feud focused on my character flaws and from which I was finding it impossible to escape no matter how far I fled. I had spent the summer of 1958 traveling by myself in Europe and, instead of returning to Chicago, had quit my job and moved to Manhattan. I had found an inexpensive basement apartment on the Lower East Side and was living off the first payment of the $7,500 fellowship Houghton Mifflin had just awarded me for the manuscript of Goodbye, Columbus, which they were to publish in the spring of 1959. I had left Chicago for good after a year in which the deterioration of trust between Josie and me had elicited the most grueling, draining, bewildering quarrels: her adjective "wicked" did not sound so alluring when it began to be used to describe me. Except for unavoidable encounters around the university neighborhood, half of the time we didn't see each other at all, and for a while, after we had seemingly separated for good, I became enamored of a stylish Radcliffe graduate, Susan Glassman, who was living with her prosperous family on the North Shore and taking graduate classes in English at Chicago. She was a beautiful young woman who seemed to me all the more desirable for being a little elusive, though actually I didn't like too much that I couldn't entirely seem to claim her attention. One afternoon I dealt the final blow to whatever chances I had with Susan by asking her to come along with me to hear Saul Bellow speak at Hillel House. Josie happened to have taken the afternoon off from work and to my dismay was in the audience too; but as Bellow was one of my literary enthusiasms that she'd come to share, neither of us should really have been as surprised as we appeared to be by the other's presence.

After the talk, Susan went off to introduce herself to Bellow; they had met once through mutual friends at Bard, and, as it turned out, in those few minutes a connection was reestablished that would lead in a couple of years to her becoming Bellow's third wife. Josie, who'd come to Hillel House on her own, superciliously looked my way while Susan was standing and talking to Bellow; when I went over to say hello, she muttered, with a sharp little laugh, "Well, if that's what you like!" There was nothing to say to that, and so I just walked off again and waited to take Susan out for a drink. Later in the evening, when I got back to my apartment, I found a scribbled note in my mailbox, tellingly succinct—and not even signed—to the effect that a rich and spoiled Jewish clotheshorse was exactly what I deserved.

What I discovered when I returned from Europe in September 1958 was that, having spent July and August working in New York for Esquire, Josie had decided against returning to Chicago and her secretarial job at the university. She'd enjoyed Manhattan and her position at the fringe of the literary life and had decided to stay on "in publishing," for which she had no qualifications aside from the little experience at Esquire. But if I was Jewish she was Jewish, if I lived in Manhattan she lived in Manhattan, if I was a writer she was a writer, or would at least "work" with writers. It turned out that during the summer she had let on to some of the magazine people she'd met that she had "edited" my stories that had begun to appear in Commentary and The Paris Review. When I corrected her and said that though she certainly read them and told me what she thought, that was not what was meant by "editing," she was affronted: "But it is—I am your editor!"

"It isn't fair!" she cried. "You have everything and I have nothing, and now you think you can dump me!"

The quarreling started immediately. Because of her desperation at finding herself purposeless in New York and unwanted by me, the exchanges were charged with language so venomous that afterward I would sometimes wind up out on the street wandering around alone for hours as though it were my life that had hit bottom. She located an apartment to sublet, moved in, and then mysteriously the apartment was lost; she found a job, turned up for work—or said she did— and then mysteriously there was no job. Her little reserve of money was running out, she had nowhere permanent to live, and none of her job interviews seemed ever to yield anything real. Repeatedly she would get on the wrong subway and call from phone booths in Queens or Brooklyn, panting and incoherent, begging me to come get her.

I didn't know what to do or whom to turn to; I felt myself being dragged way beyond my depth— and yet these were the most triumphant months of my life. Less than five years out of college, I was about to have a first book published, and my editors at Houghton Mifflin were tremendously encouraging; on the basis of a few published stories, I had already established a small reputation in New York—I was meeting other writers and beginning to enjoy feeling like a writer myself instead of like a freshman-composition teacher who'd written a few short stories on the side. This spent love affair with Josie, a shambles for nearly a year now, couldn't possibly bring down someone on my trajectory. It wasn't marriage I was worried about, marriage was inconceivable: I just didn't want her to have a breakdown, and though I couldn't believe she would do it, I dreaded the possibility that she might kill herself. She had begun to talk about throwing herself in front of a subway car—and what seemed to have exacerbated her hopelessness was my new literary recognition. "It isn't fair!" she cried. "You have everything and I have nothing, and now you think you can dump me!"

Whether appropriately or not, I felt responsible for her having come to New York that summer. The temporary Esquire opening was as a reader for Gene Lichtenstein and Rust Hills, the magazine's fiction editors; when Josie had heard of the job and expressed interest in it, I had assured Gene and Rust she could do it—I figured that if she got it, it might help, if only temporarily, to quiet her complaint about going nowhere in life. I suppose I thought of it as the last thing I would try to help her out with before I disappeared completely. Later she was to claim that if Rust Hills hadn't promised her that the job would become permanent after the summer she would never have left Chicago; she would also have returned to Chicago if I hadn't implied, in letters that I'd written her from Europe, that I wanted her to stay on after I got back to New York. Rust Hills and I had both misled her, and when she turned up at the dock to meet my boat at the end of August 1958, it was because she knew that's what I'd wanted. Waving excitedly from the pier in a white summer dress, she looked very like a bride. Maybe that was the idea.

We spent a couple of endurable evenings over the following weeks with a young English architect whom I'd met on the boat and his English girlfriend, who was working in New York for Vogue at just the kind of job Josie wanted but couldn't seem to get. One of those nights we attempted to make love in my basement apartment; that I was pretty obviously without desire put her into a rage about "all the girls you screwed in Europe." I didn't deny that I hadn't been chaste while I was traveling—"Why should I have been?" I asked—thus making things predictably worse. By November she was wandering around New York with no money and nowhere of her own to live, and eventually, when she wound up one cold morning standing with her suitcase at the foot of the cracked concrete stairs leading down to my apartment and demanding that I summon up just one iota of compassion and give her a place to stay, it occurred to me to abandon the apartment to her—forget my records and my books and the few hundred dollars' worth of secondhand furniture, and disappear with what remained of my Houghton Mifflin money. But there was a two-year lease on the eighty-dollar-a-month apartment to which I'd signed my name, there were my parents in New Jersey, whom I spoke to on the phone weekly and who were delighted that I appeared to be permanently settled back East—and there was the promise of my new life in Manhattan. There was also my refusal to run away. Fleeing and hiding were repugnant to me: I still believed that there were certain character traits distinguishing me from the truly wicked bastards out of her past. "You and Rust Hills and my father!" she shouted, weeping outside the doorway at the bottom of that dank well—"You're all exactly the same!" It was the craziest assertion I had ever heard, and yet, as though I had no choice but to take the accusation seriously and prove myself otherwise, instead of running I stayed. So did she. With me.

So the second time she turned up pregnant was early in February 1959. I won't describe our life together on the Lower East Side during the three preceding months except to say that I'm as surprised today as I was then that we didn't wind up—one or both of us—maimed or dead. She produced the perfect atmosphere in which I couldn't think. By the beginning of the year in which Goodbye, Columbus was to be published, I was nearly as ripe for hospitalization as she was, my basement apartment having all but become a psychiatric ward with cafe curtains.

How she could be pregnant was even harder to understand this time than it had been in Chicago, two years before, when it never occurred to me that the pregnancy had resulted from her failing to use the diaphragm she invariably purported to be going off to the bathroom to insert. She already had two children she couldn't raise and grievously missed— why would she go out of her way to have a third? Four months after we'd met there'd been no reason to question her honesty, unless, of course, instead of swallowing whole her story of relentless victimization, instead of being so beguiled by the proximity she afforded me to the unknown disorders of Gentile family life—to those messy, sordid, unhappy realities that inspired my grandparents' goy-hating legends—I'd had the know-how at twenty-four to cast as cold an eye on her self-presentation as she did on the men who had been abusing her all her life.

It was true that in the middle of the night there had been two, three, even perhaps four fantasy-ridden, entangled couplings in which we had somehow slaked our anger and, somnambulistically, eased the physical hunger aroused by the warm bed and the pitch-black room and the discovery of an identityless human form among the disheveled bedclothes. In the full light of morning I would wonder if what I seemed to remember had not been enacted in a dream; on the February morning that she announced she was pregnant once again, I could have sworn that for weeks and weeks I hadn't even dreamed such an encounter—I was erotically too mummified even for that. I had just come back from Boston, where I had been seeing to the galleys of my book, and it was more or less with the news of her pregnancy that she greeted my return: not only was I on the brink of being the author of a first collection of stories, I was scheduled to become a father as well. It was a lie, I knew the moment she said it that it was a lie, and I believed that what had prompted the lie was her desperation over my Boston trip, her fear that with the publication of my first book, which was only months away, my conscience would be catapulted beyond the reach of her accusations, my self-esteem elevated to heights that would have situated her too—if only she were at my side—high above the hell of all that failure.

When I told her that it was impossible for her to be pregnant again, she repeated that she was indeed going to have a baby and that if I "wickedly" refused to be responsible for it she would carry it to term and leave it on my parents' doorstep in New Jersey.

I didn't think she was incapable of doing that (had she been pregnant, that is), for by this time she was nursing a grievance against my parents too—she claimed they'd treated her "ruthlessly" during a disastrous visit she'd made to our house two summers earlier. I had gone off to spend a month by myself writing in a rented room on Cape Cod; at the end of the month, as pre-arranged, Josie had come out from Chicago for a week's vacation. Within seventy-two hours things were as hellish as they'd ever been, and we had called it quits and driven to New York. She was going to finish out the week in a hotel there, seeing the sights on her own, while I went on to New Jersey—to Moorestown, near Camden, where my father had lately been transferred to manage Metropolitan Life's local district office. I planned to stay in Moorestown for a week before returning to my job in Chicago. On the drive down from the Cape, Josie insisted on knowing why she couldn't come along. How could I treat her so wretchedly after she'd spent her savings coming all the way to Cape Cod to see me? Wasn't I grown up enough to introduce to my mother and father the woman with whom I'd lived for a year in Chicago? Was I a man or was I a child? When she wouldn't stop, I wanted to kill her. Instead I took her home with me.

That Josie wasn't Jewish hardly entered into it. What my parents saw to frighten them wasn't the shiksa but a hard-up loser four years my senior, a penniless secretary and divorced mother of two small children who, as she was quick to explain at dinner the first night, had been "stolen" from her by her ex-husband. While my mother was in the laundry room doing the family wash the next morning, Josie came in with her dirty clothes from her few days on the Cape and asked if my mother minded if she threw them into the machine too. The last thing that my mother wanted anything to do with was this woman's soiled underwear, but, as hopelessly polite as the ideal housewife in her favorite women's magazines, she said, "Of course, dear," and obligingly put them into the wash. Then my mother walked all the way to my father's office, some three miles away, weeping in despair over what I, with all my prospects, was doing with this obviously foundering woman. She had seen instantly what was wrong, everything that it had taken months for me even to begin to recognize, every disaster-laden thing from which I was unable to sever myself—and toward which I continued to feel an overpowering, half-insane responsibility. My mother could not be consoled; once again Josie was furious and affronted; and my father, with extreme diplomacy, with a display of gentlemanly finesse that revealed to me, maybe for the first time in my life, the managerial skills for which he was paid by Metropolitan Life, tried to explain to her that his wife had meant her no harm, that they had been pleased to meet her, but that it might be best for everyone if Philip took her to the airport the next day.

I was desolated, particularly since what happened was just what I'd expected— this was precisely why I hadn't wanted her to come with me. And yet on the drive down, when she'd told me how miserable she would be alone in a cheap New York hotel or, worse still, back in hot Chicago, having had, because of me, the worst possible vacation, I had once again been unable to say no—just as I'd been unable to tell her that I hadn't wanted her to join me for as little as a day when I'd first decided to go off that summer for a month on Cape Cod. I could have spared Josie her humiliation, I could have spared my mother her unhappiness—and myself my mounting confusion—if only I hadn't been so frightened of appearing heartless in the face of her unrelenting need and everything that was owed to her.

It was no wonder—though maybe it was nothing less than that, given my enslavement to her sense of victimization— that when I did get back to Chicago that fall we were together less and less, and I began to resume a vigorous bachelor life, pursuing Susan Glassman and intermittently dating a perfectly sane editorial assistant for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, whom, had I settled in for good in Chicago, I would probably have seen much more of. Bizarrely, had I remained in Chicago, where Josie was installed in a job and an apartment, instead of rushing to put a thousand miles between myself and our hopeless estrangement, she would never have wound up alone in Manhattan, positioned to throw herself on me as all that stood between her and ruination. But not foreseeing that was the least of what I didn't know, brainy young fellow that I was on my Houghton Mifflin literary fellowship.

The description in My Life as a Man, in the chapter "Marriage a la Mode," of how Peter Tamopol is tricked by Maureen Johnson into believing her pregnant parallels almost exactly how I was deceived by Josie in February 1959. Probably nothing else in my work more precisely duplicates the autobiographical facts. Those scenes represent one of the few occasions when I haven't spontaneously set out to improve on actuality in the interest of being more interesting. I couldn't have been more interesting—I couldn't have been as interesting. What Josie came up with, altogether on her own, was a little gem of treacherous invention, economical, lurid, obvious, degrading, deluded, almost comically simple, and, best of all, magically effective. To reshape even its smallest facet would have been an aesthetic blunder, a defacement of her life's single great imaginative feat, that wholly original act which freed her from the fantasied role as my "editor" to become, if for a moment only, a literary rival of audacious flair, one of those daringly "pitiless" writers of the kind Flaubert found most awesome, the sort of writer my own limited experience and orderly development prevented me then from even beginning to resemble—masterly pitilessness was certainly nowhere to be found in the book of stories whose publication she so envied and to which she was determined to be allied. In a fifteen-page explication of human depravity by one of his garrulous, ruined, half-mad monologuists, Dostoyevsky himself might not have been ashamed to pay a hundred-word tribute to the ingenuity of that trick. For me, however, it was to become something more fateful than a sordid little footnote to somebody else's grandiose epic of evil, since by the time she came to confess to me two and a half years later (and, rather as Maureen makes her disclosure to Tamopol, drugged and drunk, midway through a botched suicide attempt), by the time I learned from her how she had played her trick in Manhattan—as well as how she'd used no contraception in Chicago—we had repeatedly been in court to try to wrest her children back from her first husband. By then her daughter, a harassed, endearing, well-intentioned, ill-educated, emotionally abused girl of ten, was living in our house in Iowa City, and Josie was threatening to stab me to death in my sleep if I should ever attempt to seduce the child, whom in fact I was hoping, literally, to teach to tell time and to read. Needless to say, to this development Dostoyevsky might have allowed something more than a mere one hundred words. I myself allowed several thousand words to find an apposite, deserving setting for her scenario in the opening section of My Life as a Man, in the chapter "Courting Disaster," which purports to be Peter Tamopol's macabre fictional transmogrification of his own awful-enough "true story." For me, if not for the reader, that chapter—indeed the novel itself—was meant to demonstrate that my imaginative faculties had managed to outlive the waste of all that youthful strength, that I'd not only survived the consequences of my moral simpletonism but finally prevailed over my grotesque deference to what this wretched small-town Gentile paranoid defined as my humane, my manly—yes, even my Jewish—duty.

The urine specimen that she submitted to the drugstore for the rabbit test was purchased for a couple of dollars from a pregnant black woman she'd inveigled one morning into a tenement hallway across from Tompkins Square Park. Only an hour earlier she'd left my apartment, ostensibly for the drugstore, with a bottle in her purse containing her own urine, but as that would have revealed her to be not pregnant it was useless for her purpose. Tompkins Square Park looked run-down even in those days but was back then still a perfectly safe place, a neighborhood resting spot for the elderly, where they sat in good weather and talked and read their newspapers—more often than not papers in Ukrainian—and where the local young mothers, many of them very young and Puerto Rican, brought their children to play and run about. After a day of writing, I'd either walk over with my own newspaper—or my Commentary or Partisan Review—to an Italian coffeehouse on Bleecker Street for an espresso or, when it was warm enough, go down to Tompkins Square Park and read awhile on a favorite bench, read and look around and sometimes jot down a note about what I'd been writing that day, feeling very much the satisfactions of a young man on his own in a big city—to an ex-Newarker, a city far more mythical than Paris or Rome. If I wasn't as poor as those whose local park this was, I was still scrupulously living on the money that I portioned out to myself each week from the Houghton Mifflin fellowship; with no real desire to live otherwise, I felt perfectly at home loitering unnoticed among these immigrant Americans and their American offspring. I did not think of myself romantically as "one of them," it wasn't my style to speak of these people as The People, nor was I doing research—I knew plenty about Old Country immigrants without having to study the sociology of Tompkins Square Park. I did think occasionally, however, of how my own family and all of our family friends had evolved from an immigrant existence that had to have shared at least certain elemental traits with the lives of the Tompkins Square Park regulars. I liked the place as much for its uneventful ordinariness as for the personal resonance that it had for me.

I don't intend to suggest that my sentimental fondness for Tompkins Square Park should have given Josie pause and sent her instead to look for her pregnant woman in Washington Square Park, only a ten-minute walk from my apartment in the other direction. To the contrary, had she gone anywhere other than Tompkins Square Park, she wouldn't have been the woman whose imagination's claim on my own may well have been what accounted for her inexplicable power over a supremely independent, self-assured, and enterprising young man, a stalwart competitor with a stubborn sense of determination and a strong desire to have his own way. The same deluded audacity that made even the least dramatic encounter promising, that had prompted her, probably quite spontaneously, to sign herself into the Chicago hospital as Jewish a mere hundred days into our affair, that had inspired her to hand over to my conventional, utterly respectable mother the dirty underthings that she'd accumulated on her holiday with me, was precisely what pointed her, like a hound dog with the sharpest nose for acerbic irony, to Tompkins Square Park in order to make a responsible man of me—to make a responsible Jew of me: to Tompkins Square Park, where she knew I so enjoyed my solitude and my pleasant sense of identification with my Americanized family's immigrant origins.

And a few days later, when she'd accepted my proposal to marry her—on the condition that before the marriage she have an abortion—it was the same instinct that led her to take the $300 I'd withdrawn from the bank and, instead of going with it to the abortionist whose name I had got from an intern friend, pocket the cash and spend the day in a movie theater in Times Square, repeatedly watching Susan Hayward go to the gas chamber in I Want to Live!

Yet once she'd "had" her abortion— after she'd come back from the movies to my basement apartment and, in tears, shivering uncontrollably, told me from beneath the blankets on the bed all the horrible medical details of the humiliating procedure to which I had subjected her— why didn't I pick up then and run away, a free man? How could I still have stayed with her? The question really is how could I have resisted her? Look, how could I ever have resisted her? Forget the promise I'd made, after receiving the rabbit-test results, to make her my wife if only she got rid of the fetus—how could I have been anything but mesmerized by this overbrimming talent for brazen self-invention, how could a half-formed, fledgling novelist have hoped ever to detach himself from this undiscourageable imagination unashamedly concocting the most diabolical ironies? It wasn't only she who wanted to be indissolubly joined to my authorship and my book but I who could not separate myself from hers.

I Want to Live!, a melodrama about a California B-girl who is framed for murder and goes to the gas chamber. The movie Josie went to see (instead of the abortionist, for whom she had no need) is also to be found in My Life as a Man. Why should I have tried to make up anything better? How could I have? And for all I knew, Josie had herself made that up right on the spot, consulted her muse and blurted it out to me on the afternoon of her confession two years later.. .even, perhaps, as she invented on the spot—both to make her story more compelling and to torture me a little more—the urine specimen that she'd bought from the black woman in Tompkins Square Park. Maybe she did these things and maybe she didn't; she certainly did something—but who can distinguish what is so from what isn't so when confronted with a master of fabrication? The wanton scenes she improvised! The sheer hyperbole of what she imagined! The self-certainty unleashed by her own deceit! The conviction behind those caricatures!

It's no use pretending I didn't have a hand in nurturing this talent. What may have begun as little more than a mendacious, provincial mentality tempted to ensnare a good catch was transformed, not by the weakness but by the strength of my resistance, into something marvelous and crazy, a bedazzling lunatic imagination that—everything else aside—rendered absolutely ridiculous my conventional university conceptions of fictional probability and all those elegant, Jamesian formulations I'd imbibed about proportion and indirection and tact. It took time and it took blood, and not, really, until I began Portnoy's Complaint would I be able to cut loose with anything approaching her gift for flabbergasting boldness. Without doubt she was my worst enemy ever, but, alas, she was also nothing less than the greatest creative-writing teacher of them all, specialist par excellence in the aesthetics of extremist fiction.

Reader, I married her.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now