Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCOOL FOR KATZ

On the eve of his big show at the Whitney, Alex Katz's paintings look like the quintessential art of the eighties: frozen moments of modern life. MIRA STOUT interviews the hard-edged artist

MIRA STOUT

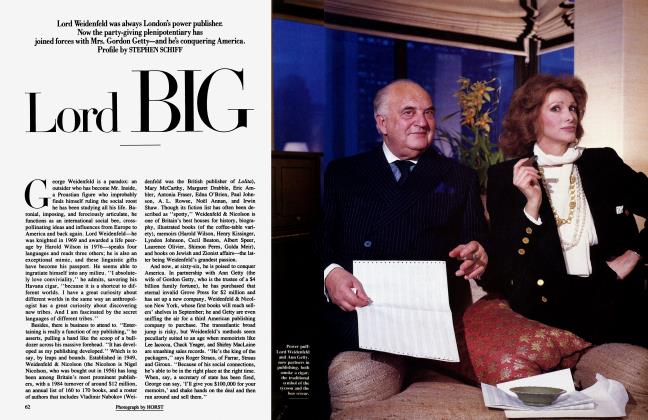

That nineteenth-century romanti cism of people having to suffer to be good is just baloney," Alex Katz once grumbled on the subject of success. Between shows at the Marlborough and Robert Miller galleries, Katz has been busily decorating the Sistine Chapels of our time—a gigantic mural in Times Square, his outsize signature for an Area installation, and cutouts for Palladium. And this month the Whitney Museum officially canonizes him with a major retrospective.

Now nearing sixty, Alex Katz may prove to be the visual biographer of the eighties. His enormous portraits of citified people—magnified and flattened out—form an insistent iconography. Katz people express operatic intimacies and antiseptic angst: it's apt that literary anthropologist Ann Beattie is at work on an Alex Katz monograph for Abrams. The artist, who once did a portrait of John Updike for the cover of Time, is, like Updike, a consummate chronicler of the northeastern intelligentsia, although Katz's view is far more chilling. His coup has been to bring the immense scale of abstract expressionism and the optical punch of billboard pop to realism via portraiture, thereby redefining it.

In his immaculate and spare West Broadway studio, the artist talked about his newest work. Saturnine and suave, Katz is handsome in a severe way. The loft (where he has lived for many years with his wife and model, Ada) is hung mainly with Katzes—giant canvases that manage to minimize even the six-foot-tall painter.

"I just try to get the surface and leave the rest," Katz explained. ''The new stuff has more and more to do with appearance rather than content. If you put people in the same designer's clothes, everyone looks anonymous. Lately I've been using Norma Kamali bathing suits."

Whitney curator Richard Marshall elaborates: ''Alex's interest in style over content is most often used as a criticism, while really it is the most positive thing about his work... .These are cool, sexless, nonnarrative paintings. They're big and stylish, and are meant to be. He reduces emotion—subverts it. People expect more narrative than they get. If people don't find them satisfying, that's fine, maybe their expectations are too high."

Although Alex Katz came of age in the abstract-expressionist years, the surface of his art bears more resemblance to the extroverted socko images of the sixties. The giant Times Square mural he designed in 1977 was a big step away from the private, internalized art of painters like Mark Rothko.

''That was one of the biggest kicks of my life," Katz says, beaming. "I always wanted to have a painting in Times Square. I wanted to see if I could knock a billboard down—if the work could hold up next to a billboard. I didn't like the idea of a Rothko—a painting that had to have its own space. If you could put it in Times Square, you could put it anywhere!"

Katz has many staunch admirers in the art world, from criticcurator Rene Ricard, who described Katz as being ''the first artist to paint eyelashes right," to editor-critic Hilton Kramer, an old Katz aficionado. ''What struck me about him twenty years ago," Kramer says, ''was the speed with which he brought to his work the look and texture of contemporary life. In one sense he provides a chronicle of the New York art world, and at the same time—like Twyla Tharp and Paul Taylor—he's perfected a style of great clarity and formal invention. People don't pay enough attention to this, because they get caught up in the subject matter."

Katz's interest in dance, both as subject and object, has led him to do several paintings of Paul Taylor's company, and for its season premiere next month, he's involved in his fifteenth collaboration with Taylor on set and costume design. Katz is also designing a project with choreographer Jacques d'Amboise. Film is another cross-reference for Katz. His CinemaScope wide-angles and cropped close-ups are obvious quotations from the movies, and he is at his most animated talking about film: "You know, I'd like to paint the way Godard shot Hail Mary—that would be a big accomplishment. Godard's movies would be better if there were more style and less content. I liked the cardboard quality of Breathless—it was much emptier than Hail Mary. I really liked the way the words hang in the air, and the way the words go with the pictures," says Katz. ''And Fassbinder's The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant was one of the greatest pictures I've ever seen. It was totally empty."

Katz's is an art of irony: his deployment of an ad-slick style in the service of a deliberately anesthetized imagery forms a risky double negative in which meaning is canceled out. On the sweetly colored surface his canvases appear benign, but the effect achieved is quite the opposite: what creeps up from behind these well-mannered friezes is a casual brutality. Katz's confrontational minimalism has earned him a number of detractors. Critic Edward Lucie-Smith said of a recent show at the Marlborough in London: ''The pictures look like enlargements of the work of a skilled illustrator in a women's glossy magazine_Katz' paintings are the ex-votos of a fashionable, rich, self-assured American life-style_His work seems radiant

.. .but strangely unfeeling and remote." ARTnews said of his show at Robert Miller in '81: "The intentional blandness and icy polish of Katz's later paintings make his work of the '50's seem emotionally eloquent by comparison."

There is little question that the aggressiveness of Katz's style unsettles people. John Russell explains it this way: "He is one of our best observers of human behavior. He is extremely shrewd. Katz's is an art that conceals art—it seems so perfectly smooth and untroubled and totally assured; it's really full of secret turmoil and wild fancy, of extraordinary formal felicities." But Katz refuses to speculate about his own painting. "It's people involved in the modem world," he says gruffly.

Katz's work is a reflection of American life seen through an inch or two of ice. It is a close-up seen from very far away—at once flattering and repellent in unexpected ways.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now