Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

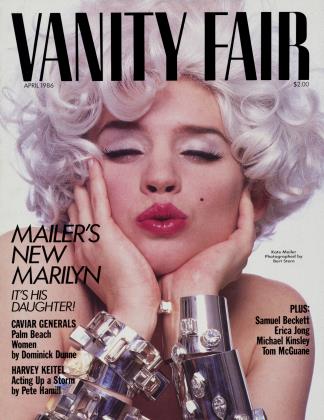

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowMailer’s new Marilyn is his daughter: Kate, born in 1962, two weeks after Monroe died. He cast her in his Actors Studio production of Strawhead, which dramatizes his continuing obsession with the sex goddess. Kate was so extraordinary we set up a photo session with BERT STERN, the photographer who captured the real Marilyn in that haunting pictorial document The Last Sitting. Sterns verdict: “No one has played Marilyn better, except Marilyn.” On subsequent pages, NORMAN MAILER offers an exclusive extract from his play

April 1986 James Atlas Bert Stern André Leon TalleyMailer’s new Marilyn is his daughter: Kate, born in 1962, two weeks after Monroe died. He cast her in his Actors Studio production of Strawhead, which dramatizes his continuing obsession with the sex goddess. Kate was so extraordinary we set up a photo session with BERT STERN, the photographer who captured the real Marilyn in that haunting pictorial document The Last Sitting. Sterns verdict: “No one has played Marilyn better, except Marilyn.” On subsequent pages, NORMAN MAILER offers an exclusive extract from his play

April 1986 James Atlas Bert Stern André Leon Talley View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now