Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

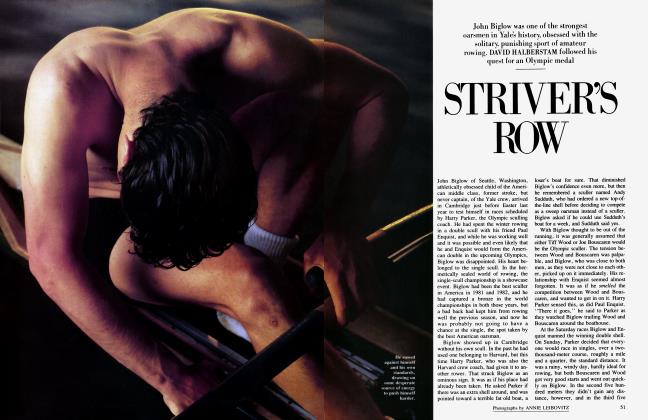

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIn Praise of the Chairman of the Board, Middle Period

The Mind's Eve

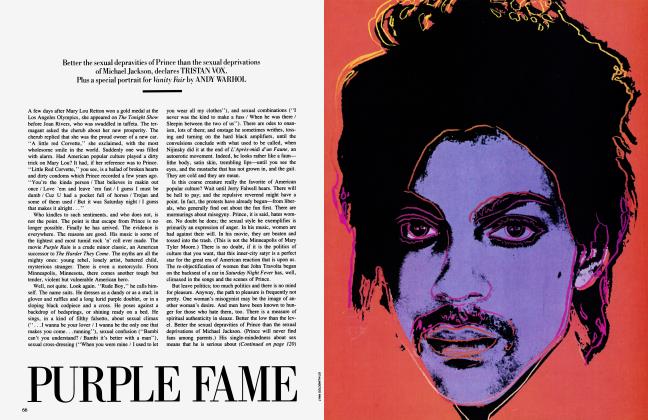

TRISTAN VOX

The social world reaches deeply. My "natural" impulses are often only the common practices of those around me; in my innermost self I am influenced. I am instructed daily, for instance, by almost all I see and hear, in an ideal of intensity. The commotion of culture at all levels—the most refined manifestations of sensibility and the most vulgar productions of the profit motive-—teaches that the true emotions are extreme emotions. Happiness is a weak form (perhaps a philistine form) of ecstasy; sadness, a weak form of agony. The significant feelings are the full and the final ones. The city itself is an argument for an apocalyptic bias of mind. Its noise alone is reason for a dream of release.

But I am not really a hungerer for endings. I merely need a little protection, and I have not found much. One carapace, however, one of my most reliable defenders against the general disturbance, has been Frank Sinatra. His middle period. To be precise, those melancholy Capitol records of the fifties.

Why Sinatra? He is so...plain, so vulgar. The critics who portentously enroll him in the bel canto tradition miss the music and miss the man. Sinatra sings as conversationally as you can sing a song and still be singing. (Hence Cole Porter complained.) But that is precisely why these records have been vinyl's great gift to solitude. To praise Sinatra's middle period is to praise the middle range of human feelings, which modernity generally despises.

Sinatra sings about inner sufferings exactly to scale. "In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning," "Guess I'll Hang My Tears Out to Dry": these are the ballads of a man in pain who will certainly not perish. In "One More for My Baby," the apotheosis of the saloon song, there is that resigned refrain "and one more for the road"; it is the second drink that stands for continuation and resistance, for the sad man's intactness, for all the precincts of his person that the loss of love failed to make founder. The most fortifying of all the songs, however, is a modest little ballad by Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers called "Glad to Be Unhappy." As Sinatra renders it, it is the very anthem of the average sorrow, of the absence of the apocalyptic attitude from the sphere of private life. It is sung by somebody still sufficiently possessed of himself to find some pleasure in his own desolation, to see his desolation as merely a stage in an undaunted search for pleasure. Perhaps the calmness of his spirit is owed to the unsensational character of what he seeks; but rarely does one seek a pleasure for which one pays with his life.

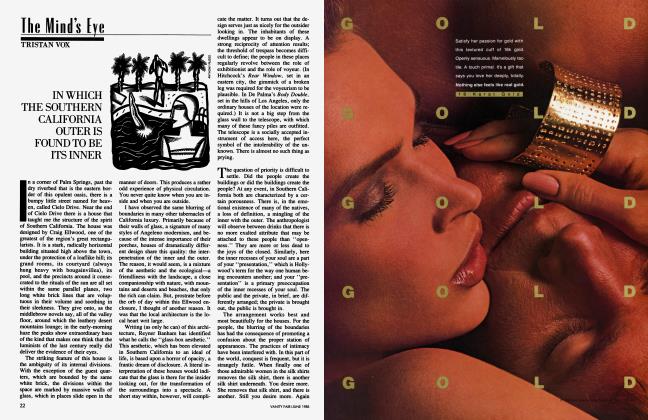

In the iconography of modem American solitude—in the history of the pictures that have propped up the souls of all the men and the women living after families, before families, between families—the covers of Frank Sinatra's records of the 1950s deserve a canonical status. Two in particular. In the Wee Small Hours, his masterpiece from 1955, showed a painted image of the singer, his brow furrowed, his tie loosened, his hat pushed back, gazing blankly from a doorway across a desolate street lit only by its lamps and the glum glow of the cigarette between his fingers. Three years later Only the Lonely appeared, which for a few dollars provided the official portrait of pitiable popular man: the singer's own face, blank again, emerging in threequarter profile from the darkness, garishly painted with the tears of a clown, seven diamonds in seven colors set strangely in the black void opposite his staring baby-blue eye. Search the dens and the salons and the basements of America. You will not find these records unscratched or their jackets unfrayed.

There are times when a song is a deliverance. Anybody who has been healed for a few hours by a jukebox, who has faced the prospect of the end of the night more bravely because of the rhyme or the rhythm vouchsafed by a radio, knows this. There is no higher form of the kindness of strangers. And there is no kinder stranger than Frank Sinatra. That is because he is (or was; he is unrecognizable and ugly now) the bard of misery's bounds. The songs Sinatra sings are called "standards" because of their frequency in the repertory of American popular music. But they are "standards" more profoundly. They are measures of the emotional mean, expressions of the manageable sentiments, statements of the spirit's commonest usages. For this reason their place in the affective history of recordplaying people is secure. But their significance is not merely statistical, or sociological. It is not that they represent a style of feeling that is typical, but that they represent a style of feeling that can help to correct the agitation that is an important part of the prevailing ideal of private experience. This is music by which to move away from the edge. If it seems, therefore, a little ordinary or a little philistine, well, it is. I daresay that Emma Bovary would have liked Frank Sinatra a lot. But I daresay, too, that Emma Bovary was exemplary, a great heroine of the limited life. Banality is frequently the quarry of beauty.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now