Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBook Marks

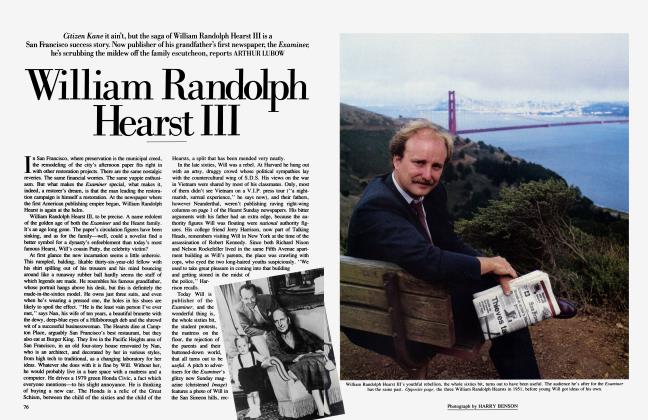

The Literary Life in San Francisco

BY JAMES ATLAS

How's New York? Still seething with hate?" It was the writer Leonard Michaels on the phone from Berkeley. Michaels, a Lower East Side boy, the child of Jewish immigrants—in other words, a pure New Yorker— has lived in Berkeley for nineteen years. He teaches in the English department there. I was eager to see him when I got to San Francisco, since I knew from his work that he wasn't one of the people who go out west and end up sitting around in hot tubs talking about their feelings. His characters—professors, writers, graduate students—have the kind of moral earnestness encountered in C.C.N.Y. cafeterias thirty years ago. They talk in the hectic inflections of New York—what Michaels calls "Manhattanese." So what was he doing in Berkeley? I wondered, driving up Shattuck past the Jungian Dreamwork Institute, the Acupressure Workshop. Did he feel a sense of exile? It seemed to me he was as far from home as his Berkeley neighbor, the Polish Emigre poet Czeslaw Milosz.

Michaels was in the living room when I arrived, practicing salsa steps. "I'm taking lessons," he explained, shuffling back and forth to the loud, brassy beat. "All I ever really wanted to be was a Latino. " When the record ended, he led me downstairs to his study. Eucalyptus fronds brushed against the window. It was late afternoon, and the fog was rolling in from the bay. There was a cleansing chill in the air. I asked Michaels what he liked about Berkeley. "People speak more slowly here, and you don't have to put too many words in a sentence." Besides, it's beautiful, he said, gesturing airily toward the window. New York had gotten impossible. On one trip there his car was stolen from in front of his mother's house; on another he glanced out the window in the morning and saw the naked dead body of a woman on a bench. "I left for the airport five hours early just to get out of town."

Michaels told me a story about a lecture he'd attended by the German sociologist Jurgen Habermas; afterward a young woman in the audience raised her hand and said, "I'd like to ask a question, but I'm not into words." Browsing in City Lights, Lawrence Ferlinghetti's bookshop, I got the sense that people out here are very definitely into words—the words of a different era. The magazine racks are crammed with journals out of the sixties: Revolutionary Worker, Political Affairs ("Capitalism ain't working!"), new versions of the old Berkeley Barb. Posters advertise the San Francisco Mime Troupe and "Kerouac: The Movie." Even the cookbooks—The Enchanted Broccoli Forest, The Book of Tofu, The Natural Foods Cookbook—give off vibes.

Actually, City Lights owes more to the fifties than to the sixties. It was here, in the shop's down-at-the-heels North Beach neighborhood, that Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and a crowd of other poets on the lam from the repressive East once congregated. It was Ferlinghetti who published Howl. Most of the places where the Beats used to gather have been replaced by strip joints; the Co-existence Bagel Shop is gone, and so is the hungry i. Still, if North Beach has a faded look, there's a lot going on in other parts of town. San Francisco is the only city in America besides New York that has a flourishing literary culture. Ever since the San Francisco Renaissance—as the influx of Ginsberg and his cronies has come to be known—the area has attracted writers drawn to the climate, the casual pace, the old-world charm. The novelists Alice Walker, Diane Johnson, and Herbert Gold live in San Francisco; Jessica Mitford lives in Oakland; Evan Connell is in Sausalito; and there must be more poets in the Bay Area than anywhere else in the country. The local gurus are Robert Duncan, whose gnomic presence dominated the scene before anyone ever heard of the Beats, and Gary Snyder, who descends from his spread in the Sierra Nevadas for periodic visits.

Browsing through Poetry Flash, the monthly tabloid that lists poetry readings in the area, you realize how diverse the scene out here is. You can hear poets associated with the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics; survivors of the once active community in Bolinas, just north of the city, where Richard Brautigan lived and died; a school of didactic theoreticians known as the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E Poets; surrealists and Dadaists and former Beatniks. A vigorous, scholarly group of poets in their early forties—Robert Hass, Robert Pinsky, and Alan Williamson—has collected in Berkeley. They owe more to the metrical stringencies of Robert Lowell than to the wideopen versifying of California poets— Pinsky and Williamson are fugitives from the East—but even their work is more unbuttoned than it used to be.

The novelists are less identifiably Californian than the poets; most of them just happen to live here because they like it. The two things everyone talks about are the weather and why they're not in New York. "The word you hear all the time is provincial," says Diane Johnson. Despite the burgeoning downtown, a cluster of imposing skyscrapers below Market Street, the city still has a kind of frontier aura. The rows of Victorian gingerbread houses and wooden triple-deckers ascending the steep streets, the clang of trolley cars in the fog, the bay "faintly ruffled by oceangoing Orient ships and ferries"—as Kerouac put it in Desolation Angels— seem out of a more innocent time. In the BART subway station, I saw something I could scarcely comprehend: people waiting in orderly queues for their train.

"You don't feel the same ferocity of literary ambition out here," notes Leonard Michaels. Alice Adams finds the city "boring," she admits, "but at least it leaves you alone." People are interested more in literature than in the business of literature. There are a handful of publishing houses—notably North Point Press, which publishes Evan Connell, M. F. K. Fisher, and Gilbert Sorrentino; a sophisticated literary journal, The Threepenny Review; and many elegant small-press editions supported by what one poet I know described as "cocaine real-estate liberals who groove on art." But—at least on the surface— there's a lot less literary hustling. "It has the feel of a small town grown big," says Jessica Mitford, who after forty years as a Bay Area radical still never misses a sit-in. "You're not always looking over your shoulder and brooding about what everyone else is doing. And where else can you make personal enemies of the D.A. and the chief of police?"

But is the city's literary life really that laid-back? After all, this isn't Esalen. "The truth is, writers are more savage here," one recent emigre confided. "Everyone thinks they're being mellow and generous, but the envy, the literary racketeering, is worse because they feel neglected." The action is elsewhere. San Francisco writers have what amounts to a mild obsession about New York. "There's a definite feeling that they're not taken seriously," says William Abrahams, who lives in nearby Hillsborough and edits books for E. P. Dutton under his own imprint. "I've paid a financial price," Herbert Gold insists, and Michaels concurs. "Living out here probably isn't so good for my career. I don't know a lot of people." On his desk is a royalty check from In-

ternational Creative Management for $2.08. When I mention my admiration for Henry Bean's False Match, a brilliant novel about Berkeley that Michaels had recommended, and wonder why it isn't better known, he snaps: "It wasn't written in New York."

Not that living in San Francisco means you're washed up in Los Angeles or New York. Diane Johnson appears regularly in The New York Review of Books, Alice Adams in The New Yorker. Michaels has written a screenplay of his novel, The Men's Club. It's not so much ambition that's frowned on out here; it's the behavior ambition provokes. There's a general feeling that New York is bad for your character. "People there worry about whether they get invited to parties," says Diane Johnson. Herbert Gold, who arrived in 1960 and stayed—"I still have a closetful of stuff in someone's apartment on Waverly Place"—recalls the atmosphere of New York in those days with distaste. "You were either a star, a Styron or Mailer, or you were nobody." No one comes right out and says so, but New York is obviously regarded as a madhouse inhabited by rude, grasping maniacs—which, of course, it is.

One night Michaels wanted to go dancing. All through dinner, he'd been drumming his fingers on the table. Finally it was time to go. We said goodbye to his wife, the poet Brenda Hillman, and their six-year-old daughter, and started off through the Berkeley Hills. Following Michaels down the winding road in my own car, I could hardly keep up. His taillights kept disappearing in the fog. I hadn't driven so fast since I was in high school. The club, down by the water, was called the Dock of the Bay. The clientele was largely black, and very well dressed. The music was loud and Latin—drums, tambourines, a soaring flute. At our table was Tom Luddy—an associate of Francis Coppola—and some people whose names I didn't catch. You couldn't hear a word anyone was saying, but Michaels wasn't into words. He wanted to get out on the dance floor and show what he could do. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now