Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

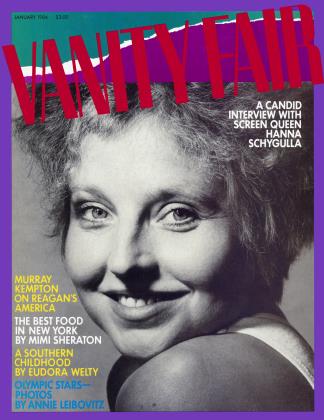

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHanna Schygulla was probably Rainer Werner Fassbinder's greatest creation...The late German director made twenty films with her and turned her into the new international sex goddess...In the interview that follows, the actress tells Gideon Bachmann what she thinks of her other directors... and what it's like to be La Schygulla...

January 1984 Gideon Bachmann Helmut NewtonHanna Schygulla was probably Rainer Werner Fassbinder's greatest creation...The late German director made twenty films with her and turned her into the new international sex goddess...In the interview that follows, the actress tells Gideon Bachmann what she thinks of her other directors... and what it's like to be La Schygulla...

January 1984 Gideon Bachmann Helmut Newton View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now