Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

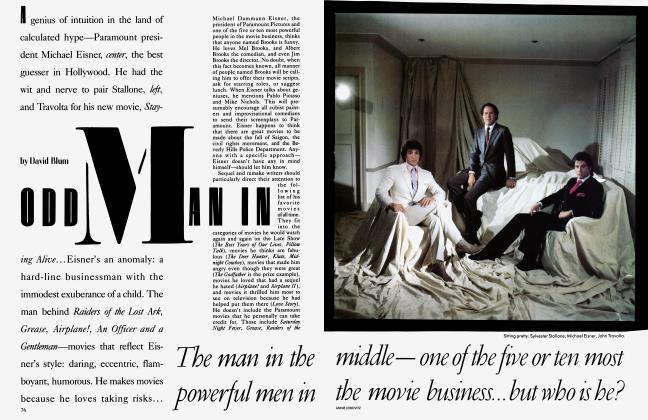

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowM R. BALANCHINE

Busan Sontag

His accomplishment is one of the glories of our century. In over sixty years of self-renewing activity, more than two hundred ballets: with rare exceptions, great artists are by definition productive. Like Picasso, in each “period” he was composing quite different kinds of work. He did not evolve from, say, ballets with stories to the plotless ballet and stay there. The costumed, romantic explicitness of Vienna Waltzes came after, not before, the stripped-down, austere configurations of Agon. He mutated, he did not progress.

Balanchine was the last of the great modernist geniuses (Eliot, Picasso, Stravinsky, Joyce, Stein, Nabokov...) who flourished as emigres, and perhaps the only one of the great modernists who had something of the naive temperament one thought had gone out with Verdi. An artist who absorbed naturally the lessons of modernism, he was free of all the superstitions of modernity. His imperial talent allowed for impudent modesty. This complete artist insisted that he was an entertainer rather than an artist; he spoke of himself as an artisan—a cook. He had the naive artist’s unremitting cheerfulness and confidence: the cult of presentness and the happy embrace of all traditions.

His training in plenitude and eclecticism began when he joined the Ballets Russes in 1924, as Diaghilev’s last choreographer. It is hard to conjure up the magnitude of the Diaghilev event of the first decades of this century; though there were dissenters, like Gordon Craig, the passionate adherence of audiences to the Ballets Russes can be compared only to the Wagnerolatry of the last decades of the nineteenth century. But by the early 1930s, when Lincoln Kirstein brought Balanchine to the United States, the situation had changed. The dance ideal incarnated by, among others, Isadora Duncan and Mary Wigman was in the ascendant: ballet was in the process of being vanquished by “modern” dance, and when Serenade (his first American ballet) was performed in 1934, what Balanchine was doing seemed marginal, the perpetuating of a retrograde art whose repertory (like that of opera) was essentially closed. Few would have suspected that it was the art of Petipa, revivified by Balanchine, that would be, four decades hence, the most influential standard for dance in America. If Balanchine is the greatest choreographer in the history of ballet, he is also the greatest modern choreographer. His “classicism” has altered and enlarged our standard of the “modern.”

It is common now to say that modernism is dead—meaning that modernism’s power to negate is compromised, exhausted. But modernism may have expired for another reason: because of the weakening of its positivity, its power to allude creatively to past traditions. What modernism was (if that is the right verb) is not a break with the past but a lens on the past. Balanchine considered himself Petipa’s heir, even saying that he modeled his choreography on the Petipa style. But he was willing to claim any genealogy. “You must go through tradition, absorb it, and become in a way a reincarnation of all the artistic periods that have come before you.” It was Balanchine’s fortune to come upon a composer who could be to him what Tchaikovsky was to Petipa. Without Stravinsky, said Balanchine, ballet would have died. Like Stravinsky’s, Balanchine’s trajectory started in Russia, passed through France. But it was here, in this encyclopedic country, that he recast his past and generated the body of his work. Balanchine had a genius for making himself at home in the world. As with the greatest artists, nothing he did was mere hackwork; the Broadway musicals and Hollywood films he choreographed in the 1930s were early evidence that he had a genuine populist streak. Then, after 1946, he could do what he wanted to do: thanks to Lincoln Kirstein, his genius was never unhoused. He had as well the imperiousness of the greatest artists. One of his last important ballets was called Robert Schumann's Davidsbundlertanze (1980). When reminded that some people in the audience might find the title a mouthful, Balanchine is said to have replied that if one couldn’t pronounce it, one shouldn’t go to see it.

The Balanchine reformation of ballet made of dance above all— dance: having discarded Diaghilev’s idea of ballet as a total theater art, Balanchine still retained large parts of the ballet vocabulary, with which he expressed formal concerns thought the prerogative of modern dance. And since the most antiballetic tradition of modern dance, once distinguished by its commitment to vernacular movements, has reembraced the ideals of the difficult and the beautiful, the territory Balanchine occupied has come to look even more central. The twoparty system in dance has not held up well. The aesthetic of “classicism”—control, simplification and intricacy, lyricism, impersonality, relative calm—is one shared equally by the ballet, as Balanchine brought it to fruition, and by the most vital traditions of modern dance. In dance, explicitly, as in no other art, perfection is the only standard.

Perfection is the only standard.

Two years ago the editors of Partisan Review asked me to furnish a contributor’s note for an old piece of mine that they wanted to include in an anthology of articles about politics. I dashed off: “Susan Sontag lives in New York, is working on a third novel, and worships George Balanchine.” When I came across the book recently in a bookstore I noted that my effusion had, of course, been deleted. Saving me from myself is what, I suppose, the editors thought they were doing. I feel for Balanchine’s work the kind of love that can indeed turn one exhibitionistic.

I began to attend the New York City Ballet in the early 1960s, which makes two decades now of a blissful polygamy, with Suzanne Farrell as the queen of my admirations. (The years she was away, with Bejart, were years in which I was mostly out of the country, too.) When the City Ballet is itl season I go to three or four performances a week, and there are many ballets I’ve seen countless times...first in the tawdry perfections of the City Center (never again will one see The Four Temperaments and Symphony in C as well as one did from the happy proximity of the first row of that preposterous balcony), now for many years from oversized auditorium to oversized stage at Lincoln Center’s New York State Theater. During intermissions I drift with other regulars between the monumental salt-and-pepper-shaker Nadelman statues, doting and quibbling about the dancers. I have even, after some resistance, picked up the custom that the hard-core fans have of referring by first names to these divinities, even if one has never so much as been introduced to them: it is always Suzanne, Peter, Karin, Merrill, Jacques, Sean, Bart ... But, invariably, Mr. Balanchine.

(As in—the words are Suzanne Farrell’s—“I dance for God and Mr. Balanchine.”)

The night after Balanchine died, April 30, I had tickets; I was coming again for virtually the same program I’d seen at the opening of the season, a few nights earlier, in particular for Symphony in C, which I see as a kind of bouillon-cube reduction of Swan Lake, Swan Lake without the plot, without the pathos; no ballet is more “up”—it is the very essence of C major. At eight o’clock Lincoln Kirstein stepped before the curtain and said, “I don’t have to tell you that Mr. Balanchine is with Mozart and Tchaikovsky and Stravinsky.” He is with us, too, he said. Then the newly orphaned dancers danced, with their steady-state smiles, most moving of courtesies, and as well as ever, at their best (ideal bodies in ideally courteous, tender, playful, yearning, accelerated transactions); and Suzanne Farrell, in the adagio of Symphony in C, never danced better, was perfection itself—exalted, extended, swooning at the end aslant the kneeling Peter Martins. There is the sadness that always accompanies great beauty, and here was all the soreness of heart one could bear. But also rapture. Real energy emanated in the world never goes tracelessly. Balanchine’s art is still streaming. ¾

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now